The presence of Romani women on screen is as old as cinema itself, with moving images of this minority projected as early as 1897 in the British film A Camp of Zingari Gypsies and somewhat later in the two versions of Carmen, one made by Cecil B. DeMille in the USA in 1915 and the other by Ernest Lubitsch in Germany in 1918, featuring Pola Negri.

The Depiction of Romani Women Behind and In Front of the Camera

The presence of Romani women on screen is as old as cinema itself.

In these early films, the Roma character was an element of mystery or the object of desire and lust. Either hypersexualised or embodying black magic, the figure of Romani women on screen reflected how the majority perceived this community, specifically the women. In other words, the representation of Roma women put forward the white male fantasy projected onto racialised, exotic bodies.

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak in her seminal essay Can the Subaltern Speak? addresses the problematic position of the Other, a woman of colour in this case, and the struggle to construct her discourse without the mediation of a white-centred ideology. Spivak wonders whether Postcolonial Studies, as an academic position of enunciation, reaffirms colonial practices instead of dismantling them. Moreover, she shows concern for Subaltern Studies: Spivak acknowledges its raison-de-être, yet she argues that the privileged position from which the knowledge is articulated prevents the possibility of granting the subaltern a voice:

‘In seeking to learn to speak to (rather than listen to or speak for) the historically muted subject of the subaltern woman, the postcolonial intellectual systematically unlearns female privilege. This systematic unlearning involves learning to critique postcolonial discourse with the best tools it can provide and not simply substituting the lost figure of the colonized. Thus, to question the unquestioned muting of the subaltern studies is not, as Jonathan Culler suggests, to “produce difference by differing” or to “appeal [...] to a sexual identity defined as essential, and privileged experiences with that identity”.’

Spivak 1988, 91

Therefore, despite the existence of intellectuals from former colonies, as Spivak is herself, she states the how impossible it is for a subaltern to speak; instead they are spoken for: ‘Representation has not withered away. The female intellectual as intellectual has a circumscribed task which she must not disown with a flourish.’ (Spivak 1988, 104)

Female filmmakers from different minority groups have proved that the subaltern can indeed have a voice and speak for themselves...

However, female filmmakers from different minority groups have proved that the subaltern can indeed have a voice and speak for themselves, albeit with great difficulties at times. Despite the cinematic apparatus channelling the white male vision, along with his fantasies and interests, women nevertheless managed to appropriate and reshape the filmic language to articulate their own experience.

In the following pages I will examine several films by Romani women directors who use cinematic devices to form a different, female- and Roma-centred subjectivity, in the process redefining the Romani identity and exploring the female Roma experience. The questions that guide my analysis are the following: How do the directors position themselves towards their subjects? Who do they address? How do they navigate between the static binary opposition of tradition versus modernity? What genre do they choose to best express themselves? To answer these queries, I will first provide background on the feminist perspectives that inform my approach.

In 1975 Laura Mulvey published Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, a decisive text for feminist spectatorship, where she revealed how traditional cinema reinforces the socially established sexual differences, and how it operates as a phallocentric tool to fix women as an object of male sexual desire. Mulvey, through the prism of psychoanalysis, studies how ‘the magic of Hollywood style (and of all the cinemas which fell within its sphere of influence) arose [...] from its skilled and satisfying manipulation of visual pleasure. Unchallenged, mainstream film coded the erotic into the language of the dominant patriarchal order.’ (Mulvey 1976, 59)

The cinematic apparatus creates ways of looking, and the gaze with which the audience identifies is the male gaze. Mulvey’s study triggered further analysis not only of traditional film, but also called attention to the way alternative gazes are created and how female subjectivity can be constructed.

However, in order to grasp the complexities of these films by Romani women directors, it is necessary to go beyond Mulvey’s proposal and acknowledge that there is no single female subjectivity, but rather multiple positions of female subjectivity, where racial and socio-economic factors play an important role. Assuming all women have the same world experience simplifies and reduces female reality into a monolithic outcome.

bell hooks adds to Mulvey’s analysis: ‘Feminist theory rooted in an ahistorical psychoanalytic framework that privileges sexual difference actively suppresses recognition of race reenacting and mirroring the erasure of black womanhood that occurs in film.’ (1992, 123) Indeed, Black and Third-World Feminists provide a discursive framework that facilitates the study of Romani women both behind and in front of the camera.

Despite the importance of acknowledging the heterogeneity of female Romani filmmakers, being perceived as a racialised voice is a common characteristic of their work. Other characteristics are displacement – Roma being depicted on screen as enduring forced geographical relocation (in opposition to the romanticised wandering often associated with this community) – and the symbolic erasure of their presence in the public sphere.

Pertinently, Hamid Nacify explains:

‘Immigrants, refugees, exiles, nomads, and the homeless also move in and out of these discourses as metaphors, tropes, and symbols but rarely as historically recognized producers of critical discourses themselves.’

Nacifz 1993, 2

Romani women filmmakers reclaim their bodies and voices with their work, rejecting their passive role as exotic illusions and articulating their own positions.

The Self-Definition of Romani Women

The process of identity construction has been a central concern for female filmmakers, especially for racialised and/or displaced minority groups. Stuart Hall’s reflection on the complex process of identity-building illustrates the fragile position of Romani women:

‘Identity is formed at the unstable point where the unspeakable stories of subjectivity meet the narratives of history, of a culture. And since he/she is positioned in relation to cultural narratives which have been profoundly expropriated, the colonized subject is always somewhere else: doubly marginalized, displaced, always other than where he/she is, or is able to speak from.’

Hall 1996, 115

Sociologist, director, curator of the Film Section.

Katalin Bársony is an award-winning documentary filmmaker and executive director of the …

The question remains: What does it mean to be a Romani woman? This is a central question Katalin Bársony (Hungary) poses in her work as a director, producer and head of the Romedia Foundation. The Foundation is an independent organisation run by Roma, whose purpose is to inform the wider public on the realities of the Roma community and their experience, while establishing the need to fight stereotypes. In this spirit, Bársony directed and produced Mundi Romani (2007–2011), a film series portraying Roma from around the globe.

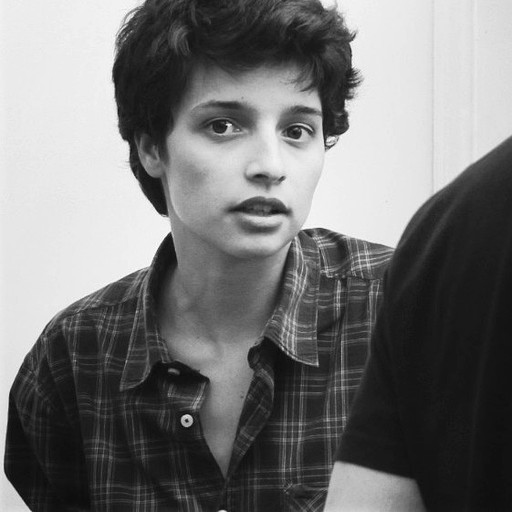

Galya Stoyanova is a photographer, aspiring documentary film director, and member of the IRFC (International Romani Film Commission). In 2012 …

Similarly, Galya Stoyanova from Bulgaria explores Roma womanhood in her debut film Pages of My Book (Hungary, 2013). This film, as the synopsis points out, not only criticises the non-Roma majority society but also explores Stoyanova’s own attitude to the Romani stereotype. Stoyanova’s self-representation, as the subject of her own film, involves a traditional Romani dress and a camera – two elements that are initially striking because they don’t seem to belong together in the same frame. Yet this unusual combination of tradition and technology is only the starting point for the director’s staging.

With camera in hand, Stoyanova walks the streets of Budapest documenting the reactions of passers-by. She is stared at, but in return she also looks back.1 The camera, as an extension of her, becomes a tool – a weapon with which she fights back against the majority. We hear the director in voiceover saying:

‘I thought that dressing like traditional Roma would be challenging for the people around me, but on the contrary it was challenging for me.’

The short film is a sociological study to some extent, an experiment where Stoyanova challenges not only the majority society but above all herself, by being treated as the Other. The film is in fact ‘pages of her book’, as the title reminds us, a story that she writes, and where she defines her own identity. The possessive adjective ‘my’ in the title is important, as it clearly states whose voice we hear.

Pages of My Book | directed by Galya Stoyanova | »Pages of my Book« is a short film from 2013, which was based on a performance acted out by Galya Stoyanova herself.

Rights held by: Galya Stoyanova | Licensed by: Galya Stoyanova | Licensed under: Rights of Use | Provided by: Galya Stoyanova – Private Archive

Laura Halilovic, a young, aspiring Romani director, was born in 1989 in Piemont, Italy, to a Romani family who originally came from Bosnia-Herzegovina. …

Laura Halilovic (Bosnia-Herzegovina/Italy) is also concerned with the portrayal of identity in her documentary Eu, familia mea si Woody Allen (Me, My Gipsy Family and Woody Allen, Italy/Romania, 2010). The director opens the film by recounting her complex identity:

‘I was born in Italy, my identity document is Italian, but my passport is Bosnian, yet my identity is a different one, I am Romani.’

With this claim, Halilovic initiates a journey of self-discovery. The film can be considered a coming-of-age story where the director reflects on the balance between her dreams and expectations in her family.

Halilovic’s own voice is decisive in this documentary: she not only states her own mind to her family when she refuses to marry the man chosen for her, but she also claims her place in the cinematic circle. The mention of Woody Allen goes beyond her genuine admiration of the avowed filmmaker. I believe this symbolic gesture bears a deeper meaning as she inscribes herself within a larger cinematic tradition, thus securing her position as a director.

Me, My Gypsy Family and Woody Allen | directed by Laura Halilovic | The Film can be received as a coming of age reality movie focusing on the »Bildungsroman« of a young girl with »Gipsy roots« who searches her place as a migrant of more traditional lifestyle in a modern, Western society.

Rights held by: Laura Halilovic | Licensed by: Zenit Arti Audiovisive | Licensed under: Rights of Use | Provided by: Zenit Arti Audiovisive (Turin/Italy)

Vera Lacková is a Romani filmmaker who graduated with a degree in media and journalism from Masaryk University in Brno, Czech Republic. During …

Discovering identity, in this case discovering Roma identity, is the point of departure in the Czech documentary Alica (2015). In the film Vera Lackova from Slovakia converses with Alice Sigmund Heráková, whose mixed ethnicity – Czech and Roma – puts her in a privileged position to analyse the complex relation between Roma and the majority society in the Czech Republic, as noted in the synopsis. Lackova, who also appears in the documentary, creates an intimate atmosphere for the interaction by including scenes at Alica’s home, for example, where she shares her experiences over a coffee or when cooking a meal; these scenes resonate well with a female audience, for whom certain spaces, such as the kitchen, became not only opportunities to strengthen sisterhood, but also a site of resistance through everyday practices.2

Alica | directed by Vera Lackova | The protagonist of this short documentary film is Alica Sigmund Heráková, who discovers at the age of 25 that she has Roma origin on her father’s side.

Rights held by: Vera Lacková | Licensed by: Transitions (TOL) | Licensed under: Rights of Use | Provided by: Transitions (Prague/Czech Republic)Tradition and Modernity as Complementary

Women of colour are frequently defined by a set of binary oppositions; however, films by Romani filmmakers break through this dichotomy in many aspects. The filmmaker and theorist Trinh T. Minh-ha warns:

‘The precarious line we walk on is one that allows us to challenge the West as the authoritative subject of feminist knowledge, while also resisting the terms of binarist discourse that would concede feminism to the West all over again.’

Minh-ha, 1992, 153

This observation aptly points out the dichotomy of tradition versus modernity, where the former is seen as being synonymous with either underdevelopment or purity and the latter with advancement or soullessness, depending on the perspective. Yet the construction of subjectivity in these films offers a continuum between these apparent polarities. For instance, Stoyanova in Pages of My Book (Hungary, 2013) points out her insecurity about her traditional appearance and comments on her fear of encountering the looks of the majority. This attitude changes when an elderly Romani woman praises her for her beauty. Her strength to complete the project and shed her fears comes symbolically from an older, more traditional generation which lends her support.

Director and scriptwriter Katariina Lillqvist was born in 1963 in Tampere, Finland, and currently lives and works in the Czech Republic. After …

The connection between generations is a recurrent aspect in the cinematographic work by Romani women. Passing on knowledge from elders to the next generation entails the creation of an oral archive which is critical for the existence of the Roma community. The women – who are mothers and educators – are responsible for this transmission.

Mire Bala Kale Hin / Tales from the Endless Road (Finland, 2002) is one of the puppet film series by Finnish Romani director Katariina Lillqvist in which she explores the act of storytelling while also contributing to the Roma oral archive. As noted in the synopsis, the tales are framed as a grandmother’s storytelling session with her granddaughter; the grandmother introduces the audience to the stories with the opening line ‘Once upon a time’, thereby recalling the genealogy of the Roma community.

The director, as a modern storyteller, becomes the guardian of knowledge, passing it on, as does the grandmother, to the spectator. In a similar manner to a palimpsest, the film rewrites and adds to the previous narration. Naficy notes that cinema is like a document of memory:

‘[They] are using the film’s frame as a writing tablet on which appear multiple texts in original languages and in translation in the form of titles, subtitles, intertitles, or blocks of text.’

Naficy 2001, 25

Films not to forget

Louise (Pisla) Helmstetter (France) also examines the importance of intergenerational knowledge, but she takes a different approach to remembering the past and the customs of her community. From the Source to the Sea (France, 1989), is a film about the traditional pilgrimage Romani people take to Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer to venerate Saint Sarah, nostalgically harking back to the times when Roma wandered freely and were close to ‘Mother Nature’.

The documentary is like a poem: the lyrical form is conveyed not only through the voice of the narrator, but also through various scenes such as the Helmsetters enjoying nature, diegesis with birds singing in the background, and long shots of symbolic Roma items such as the wheel. All these details allow for the construction of a subjective voice that establishes an intimate connection with the viewer.

However, the illusion is shattered by the editorial work. The juxtaposition of general shots using a travelling camera with shots by a hand-held camera prevents the audience from forgetting the artifice of the cinematic apparatus. Traces of home video-making, as noted in the synopsis, prevent this documentary from having a ‘smooth’, suture-like development. I argue that the author aims to break with the ethnographic, ‘objective’ documentary style, revealing instead the artifice and fictional character of this subgenre.

If we consider documentaries as a cinematic form of oral tradition, which are highly meaningful for the Romani community, then for example testimonies from World War II must be understood as a homage to those forgotten by history. This is the central theme of the collaborative work between Katrin Seybold and Melanie Spitta in Das falsche Wort: Wiedergutmachung an Zigeunern (Sinti) in Deutschland? (Germany, 1987). This documentary on the Pharrajimos goes beyond condemning the atrocities of deportations to concentration camps and denouncing the majority society for forgetting about the Roma victims, in order to report too on the inadequacies of the German government’s system of reparations.

Das falsche Wort underlines the sufferings of German Sinti and Roma and criticises German society for their lack of effort in honouring the memory of the Romani victims of the Porrajimos. Simultaneously, the film proposes that historical memory should be recovered by collecting the testimonies of survivors and relatives of the victims. The slow pace of the film and minimal editing, especially during the interviews, allows the spectator to participate along with the directors in the act of listening and thus honouring the memory of the murdered. In this manner, the documentary becomes a form of activism, an act of advocacy for recuperating the lost voices in this historical narrative.

Documentary as a Form of Activism

Devoting a documentary to a cause is a recurrent urge for female Romani directors, and one shared by many filmmakers who are members of silenced minorities. A documentary is a natural site of resistance where women can cultivate their response to systemic marginalisation. Thomas Vaugh, coining the term ‘committed documentary’, defines this practice as follows:

‘By commitment I mean firstly a specific ideological undertaking, a declaration of solidarity with the goal of radical socio-political transformation. Secondly, I mean a specific socio-political positioning: activism, or intervention in the process of change itself.’

Vaugh 1984, xiv

This is the approach taken by Portuguese director Leonor Teles in her lyrical and yet violent film Batrachian’s Ballad (Portugal, 2016). The director questions the Portuguese tradition of placing ceramic frogs at the entrance of houses or businesses in order to ward off Roma. Not only does Teles bring the viewers’ attention to this fable but she also takes action, rebelliously smashing the animal sculptures while shooting the film.

As put forward in the synopsis, the director justifies her actions: ‘It was necessary to break the frogs. If I hadn’t broken them, if I had done nothing to stop that, I wouldn’t be truly addressing the issue, I would be merely concealing it’. The act might be seen as symbolic, yet it is immediately transformative of its own reality.

Leonor Teles was born in 1992 in Vila Franca de Xira, Portugal, to a family with roots in the local Romani community. She has a degree in film …

Batrachian’s Ballad | directed by Leonor Teles | This short experimental film is both fresh and provocative, its an example of a critical approach towards a representational tradition full of clichés and commonplaces.

Rights held by: Leonor Teles | Licensed by: Portugal Film | Licensed under: Rights of Use | Provided by: Portugal Film (Lisbon/Portugal)Conclusion

Filmmaking is necessary for Romani women in order to claim their power in society. In conferences and interviews, Katalin Bársony often highlights the importance of technology, namely cinema and television, in empowering Romani people and combatting ‘antigypsyism’. The documentary as a genre fits the politics of advocacy best, for it provides a structure in which the director can communicate with the viewer, thereby creating an intimate and unmediated relationship.

The position of the filmmaker is a difficult one. As Galya Stoyanova, someone who is aware of the responsibilities that come with this representation, underlines in an interview with Romedia:

‘People today have this huge expectation on your shoulders being a filmmaker; they think you should know so much [...]. Specially documentaries, they are one of the hardest [...]. I think the title of being a filmmaker is very heavy.’

Romani women, in front of and behind the camera, or in both positions simultaneously, as is the case with Stoyanova, Lackova and Halilovic, are all keenly aware of the challenges of cinematographic work, yet they have embarked on the journey of regaining their voice in order to speak up. Romani female directors have broken the silence that has been imposed on them as subalterns, and have begun gaining ground in the struggle for power that is implicit in the act of representation.

Rights held by: Bohumira Smidakova | Licensed by: Bohumira Smidakova | Licensed under: CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International | Provided by: RomArchive