He began the task of recovering, organising and classifying the basic structures of Gitano flamenco singing.

With this premise in mind, he began the task of recovering, organising and classifying the basic structures of Gitano flamenco singing. It was a true labour of love that consumed him, body and soul, resulting in the compilation of an authentic handbook of flamenco singing for future.

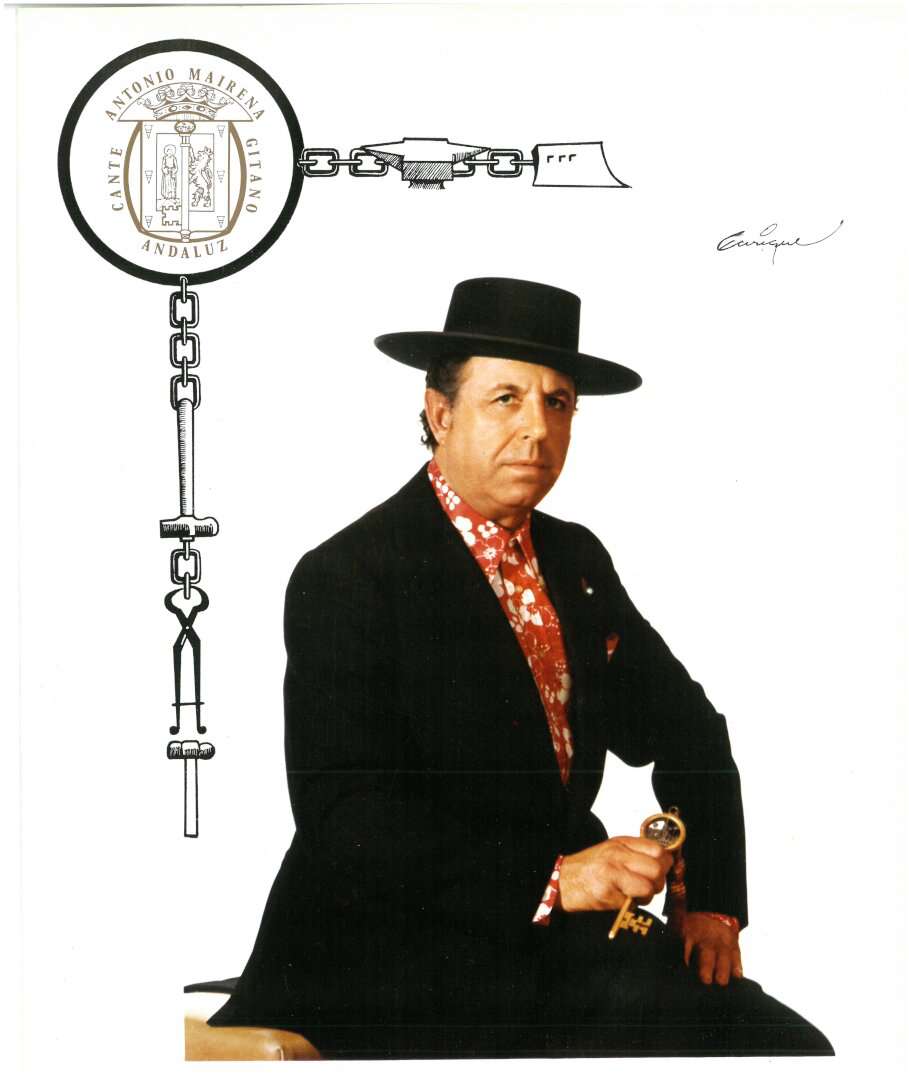

The second and third dates would each come in the form of recognition: in 1959 he was named honorary director of the Cátedra de Flamencología in Jerez de la Frontera (1959) and in 1962 he received the ‘Llave de Oro del Cante’ [Golden Key of Flamenco Singing].

Now acknowledged as a maestro, from this point on Antonio Mairena carried out his mission as a ‘disciple’ through a series of projects that he would bring to fruition:

Mundo y Formas del Cante Flamenco [The World and Forms of Flamenco Singing]

Once he had been honoured with the Llave de Oro del Cante, Antonio Mairena found himself in a position to unveil his ‘gospel’ about flamenco. He first created the category Cante Gitano Andaluz to refer to Roma flamenco music. However, all those years of field research and musical reconstruction had to be expressed in a way that would allow the world to know about the origins of flamenco singing.

Towards this end, he needed to enlist a professional writer who was not only sensitive to flamenco but also harboured a love for the genre – and he found the right individual in poet Ricardo Molina Tenor. Together they wrote the book Mundo y Formas del Cante Flamenco, which was published by Revista de Occidente in 1963.

Festival de Cante Jondo Antonio Mairena

This flamenco festival established in the early 1960s provided Antonio Mairena with a suitable framework for his mature work, where he could present flamenco singing, guitar-playing and dancing with absolute dignity.

Although the highly regarded Utrero flamenco festival had been running since 1957, Mairena wanted to set up his own festival in his home village, operating according to the principles he propounded. A Festival de Canciones y Cantos Flamencos de Mairena [Festival of Flamenco Songs and Singing by Mairena] with a singing competition had already taken place there in 1962 as part of the patron saint’s festivities. The first Festival de Cante Jondo Antonio Mairena was held on 5 September 1964.

La Antorcha Del Cante [The Torch of Song]

Once the festival had been established, the next step was to organise a singing contest which would obviously be overseen by Antonio Mairena himself. The prizewinner of the first Concurso de Cante Jondo contest was Juan Peña, known as ‘El Lebrijano’.

However, the maestro of Los Alcores wanted to differentiate this competition from others of its like, and so established the ‘Torch of Song’ as a prize, which was awarded for the first time in 1965 – to his own brother, Manuel Mairena, who was twenty-five years his junior.

La Gran Historia del Cante Gitano Andaluz

Once Antonio Mairena’s theories about the origins and genesis of flamenco singing had been laid out in a book, he sought to produce audio evidence of the same, as the legacy of a lifetime devoted to recovering and restoring the songs. And this is what he did with the set of three LPs La Gran Historia del Cante Gitano Andaluz, which was brought out by Columbia in 1966. The cantaor himself was accompanied by guitarists El Niño Ricardo and Melchor de Marchena.

Just as he hoped his book would enlighten flamencologists about his own research into the history of flamenco singing, his aim with the recordings was to provide future generations of singers with guidelines for the orthodox interpretation of this music.

Tributes to the Maestros

Antonio Mairena was well aware that his temple of flamenco singing would have to include icons to symbolise the fundamental pillars upon which he had built his flamenco ideology, known as ‘Mairenismo’. For this reason he tirelessly promoted admiration of these icons among flamenco fans by means of tributes, statues and renamed streets and squares.

Thus, Joaquín el de la Paula, Manuel Torre, Diego del Gastor and in particular ‘Niña de los Peines’ are honoured and revered with all the solemnity that these great maestros of Flamenco art no doubt deserve. Flamenco singer Pastora Pavón – known as La Niña de los Peines – is as important for Andalusian culture as figures like composer Manuel de Falla, lyricist Federico García Lorca and painter Bartolomé Esteban Murillo.

Flamenco in Universities

Some intellectuals, particularly from the Generación del 27 [Generation of 27, an influential group of Spanish poets from 1923 to 1927] onwards, were interested in the mysterious world of flamenco and occasionally dabbled in it, either by studying the sources or by inviting flamenco artists to their cultural gatherings.

He understood that flamenco would acquire prestige if the cultural elite took an interest in it that went beyond folklore, viewing it instead as cultural heritage.

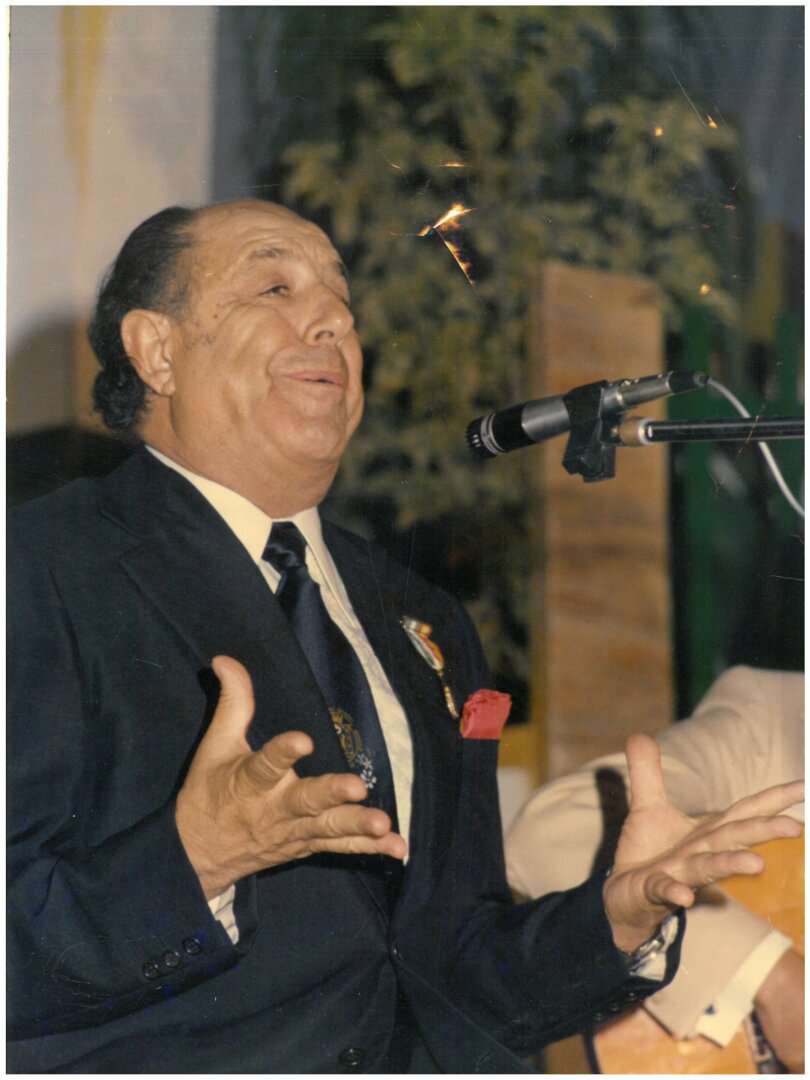

Many flamenco performers were invited to sing or speak about flamenco at universities, but Antonio Mairena – who was incessantly pained by his lack of formal education – understood that flamenco would acquire prestige if the cultural elite took an interest in it that went beyond folklore, viewing it instead as cultural heritage. He especially wanted to spark the interest of young scholars, who would later take up important university posts.

From the 1960s onwards he became a frequent presence at flamenco conferences, both as a speaker and as a performer of the music. The defining moment in his burning desire to bring flamenco to the highest spheres took place in 1963, in the auditorium of Universidad Hispalense in Seville when he proudly presented La Niña de los Peines at the presidential table, next to the university’s rector. In his view, this symbolised the social and cultural recognition of Roma flamenco singing.

Flamenco in the Media

Antonio Mairena was intelligent enough to understand that the influence of books, records, recitals, gathering and conferences would be much greater if reported in the media. Spreading information about flamenco through the press, radio and television was thus essential for educating the general public.

For this reason Mairena encouraged a media presence at flamenco events, with festival broadcasts, radio talk shows, interviews, etc. He always made himself available for interviews and consultants with even the most junior of reporters, but also regularly met up with more experienced journalists to coordinate the planning of flamenco events.

Monument to Cante Grande Gitano

Antonio Mairena spent his entire life fighting for an ideology that he promoted with uncommon passion, based on his conviction that contemporary flamenco contains a series of song forms which, in terms of their history and evolution, have always belonged to the Andalusian Roma minority because they were produced by familias cantaoras, or families of singers from the Andalusian lowlands. The series includes four basic forms: tangos, tonás, seguiriyas and soleares. This model was preserved for posterity through the construction of a monument to Cante Grande Gitano, which was unveiled in Mairena del Alcor in 1968. At that time Antonio Mairena was at the height of his fame, possessing such knowledge and power that no one disputed his huge influence.

Casa del Arte Flamenco

For Antonio Mairena, the most appropriate venue to present the purest manifestation of flamenco art (‘pure’ in the sense of purified and free of adornment) was the traditional flamenco gathering of musicians and enthusiasts known as a peña Flamenca. He considered this the ideal place to see and hear flamenco because of the sense of respect and community among those present – but also because it was the best forum for discussing the ins and outs of flamenco in lively debates with diverse opinions.

For this reason, Antonio promoted the establishment of new peñas that sprang up wherever there was flamenco. He would accept their invitations with the greatest pleasure, in the knowledge that his presence was crucial as a means of supporting and defending them, and it goes without saying that a peña was created in 1971 in his hometown of Mairena, which he christened Casa del Arte Flamenco, or House of Flamenco Art.

Autobiography

Antonio Mairena knew that he would have to write his own biography; the project could not be entrusted to biographers who would not understand the essence of his flamenco roots, and he did not wish to leave anything open for interpretation.

Thus, just as he had done for Mundo y Formas del Cante Flamenco, he found the ideal writer to transcribe his memoirs. This was the poet Alberto García Ulecia, who, as he explained in his notes, was ‘simply putting in writing what the singer wanted to express in these pages’. He added,

‘Any retouching I’ve had to do for certain spontaneous statements is purely morphological or structural; my mind was always at the service of the author’s thoughts, with the sole aim of facilitating communication and comprehension for the reader’.

The autobiography, called Las Confesiones de Antonio Mairena, was published by the University of Seville in 1976.

Posthumous Work

Interestingly, maestro Mairena’s life ended at a point when he was immersed in activity, leaving behind two posthumous works: a book entitled Joaquín el de la Paula: Gran artífice del cante por soleá de Alcalá (published in 1984), and an LP, El calor de mis recuerdos (which appeared the year before that, in 1983).

These works almost seemed to be premonitions that completed both the circle of life and his destiny: the book as a tribute to his first maestro and mentor, and the audio recording encapsulating the very essence of Gitano flamenco singing. He was also working on a publication about the life and work of Manuel Torre – and then there was his grand project, the Antonio Mairena museum, which has still not been completed.

It had always pained him to note just how many flamenco artists lacked the funds to live out their old age in comfort.

As an expression of gratitude, he transferred the rights for his final audio recordings to the Institución para la Tercera Edad de los Artistas Flamencos [Institution for the Third Age of Flamenco Artists], an organisation which now no longer exists. It had always pained him to note just how many flamenco artists lacked the funds to live out their old age in comfort.

Lastly, his personal correspondence is of great significance. He was a great letter writer with friends and admirers, particularly as a gesture of gratitude. But at the same time, he was aware that these documents would end up in the public domain. Thus he used the letters not only to show his affection for the person he was writing to, but would often refer to his ideas and objectives regarding flamenco.

It would be impossible to list all the awards and distinctions he received, not only throughout his life but also posthumously. For this reason, we have only listed those which carry the greatest institutional prestige: