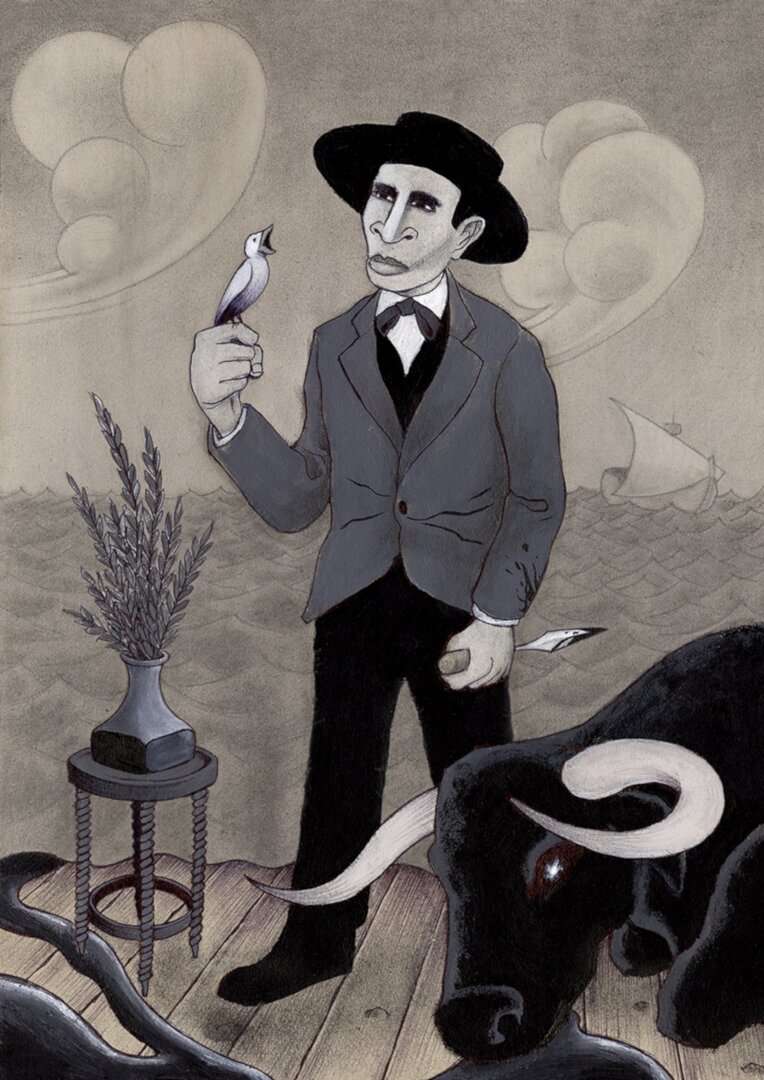

Enrique Jiménez Fernández, gitano and known as Enrique ‘El Mellizo’, was born in Cádiz in 1848 and died in Seville in 1906. As someone who possessed the qualities both of a great creator and a great performer, he has gone down in the history of flamenco singing as one of the greatest musicians of the art form.

Enrique ‘El Mellizo’

His private and professional life was lived out almost entirely in his hometown of Cádiz, where he combined the professions of working in the municipal slaughterhouse – a trade inherited from his father – with assisting famous bullfighters from his city as a puntillero, delivering the coup de grace to the dying bull.

These were environments in which flamenco enjoyed an all-important presence. He soon discovered he possessed innate qualities for flamenco singing and took a great interest in it, later drawing upon it to reproduce and personalise the forms. At the same time, he took advantage of his interpretive qualities to sing in the cafés cantantes [music bars] of Cádiz, such as La Jardinera, El Perejil and La Filipina, as well as at private gatherings and parties.

The fame of this cantaor gitano soon spread beyond his home town, and singers from the rest of Andalusia as well as Spain in general would seek him out to hear and learn about his innovatory techniques for singing existing sings.

He was married to Ignacia Espeleta Ortega, whose family had strong roots in the worlds of bullfighting and flamenco. As the daughter and sister of famous bullfighters and flamenco singers, she provided Enrique ‘El Mellizo’ with the ideal atmosphere for developing his main interests: flamenco singing and bullfighting.

He had eight children with Ignacia, three of whom outlived him: Antonio, Enrique and Carlota. Although the two sons, known in the flamenco world as Antonio ‘El Mellizo’ and Enrique ‘El Morcilla’, were less renowned than their father, they did possess his singing talent, and they proudly carried on the task of preserving and passing on his exceptional oeuvre. ‘El Mellizo’ died of pulmonary tuberculosis aged just fifty-eight. His passing triggered mourning throughout the flamenco world, and particularly in his city where he was afforded a funeral with the highest honours.

Enrique ‘El Mellizo’ embodied the purest essence of creatividad gitana, or Roma creativity: he transformed the sounds and put them in order, providing the necessary link between archaic and popular sounds, and turning them into essential reference points that made flamenco singing what it is today.

His cantes that became part of history include styles for soleá, seguiriyas, malagueñas, alegrías, tientos and saetas. He created three styles for soleá:

The first of these is an introductory soleá which is very popular among flamenco artists – a composition that Enrique ‘El Mellizo’ would spread in the last third of the nineteenth century, and which is one of the most widely interpreted in flamenco recordings. The fact that the various interpretations have kept the same structure gives an idea of how well-rounded and polished this melody is. In the same way, it tells us a great deal about its creator’s concept of flamenco singing: a very beautiful melody joined to a strong emotional charge with the use of linked phrases and sliding notes. Furthermore, this is a modern take on flamenco singing compared to previous forms, which were musically harsher and rougher with a less pronounced melodic arc.

The similarity with melodies from other areas of flamenco singing, such as La Serneta’s utrera and Joaquín el de la Paula’s soleá de Alcalá, shows that not only were the main singing families of the era in contact with each other, but there was also a mutual influence on their cantes, which nonetheless retained the distinct personalities of their creators.

In this sample style from a recording by La Niña de los Peines, the first of his soleá creations can be heard: external audio link

Bayetita de la negra

que en mi cuerpo quiero vestir.

Bayetita de la negra

que mi cuerpo quiero vestir;

porque es la propia librea

para todo el que sabe distinguir.

Bayetita de la negra

yo mi cuerpo quiero vestir.

Clothed in black

is how I want to dress.

Clothed in black

is how I want to dress.

It is the proper attire

for a discerning person.

Clothed in black

is how I want to dress.

The second soleá style is a cante de cambio or cante de cierre, which is appropriate for upping the tension or simply coming to a powerful ending. As in the previous style, the lovely melody and its great emotional charge evoke its composer’s musical beliefs, allowing us to imagine the qualities that ‘El Mellizo’ himself must have possessed as a singer: a sophisticated performer with a powerful voice, who also had a tendency for strong emotions, as evidenced by the linking of musical phrases and the melodic ascents and falls in the beginning and end of the lines.

In the following sample, we hear Manuel Torre interpret this style of soleá: external audio link

Que le ruegues

a Dios quiero.

Que tú le ruegues a Dios

para que me alivie las penas

que tengo en mi corazón.

Omaíta de mi alma

quiero que le ruegues a Dios.

I want you

to beg God.

That you beg God

to ease the pain

I feel in my heart. ,

Mother of my soul,

I want you to beg God.

Although the third contribution by Enrique ‘El Mellizo’ to the soleá style is the least known and interpreted of the three, it is probably the oldest. Like the other two, it presents a continuous, unbroken melody line, making it a difficult style to execute.

Juan Mojama, a Roma from Jerez, recorded this third style: external audio link

Las que en el silencio estén.

Que me quitan de la vera

de quien yo camelo bien.

Que redoblen las campanas

las que en el silencio estén.

Those who are silent

take me away

from the person I love.,

Let the bells ring out,

those who are silent.

The creative flow of Enrique ‘El Mellizo’ was by no means limited to the soleá form, and his talent for composition can also be seen in the repertoire of siguiriya styles that have come down to us. Specifically, two creations are attributed to him. The first is possibly an interpretation that Enrique himself made of other previous Roma siguiriyas. It is likely he was heard singing them, and thus they came to be associated with him. Moreover, there are references indicating that Enrique collected money to exempt his son from performing military service at a time when Spain was at war, so it is quite possible this verse alluded to that situation.

The great maestro Antonio Mairena recorded it like this: External audio link

Y qué vergüenza.

Y qué vergüenza más grande

y me has hecho pasar.

Pedir limosna.

Limosna mango, de puertecita en puerta,

para tu libertad.

What shame

What tremendous shame

you inflict upon me.

To go begging for alms.

I go begging door to door

for your freedom.

The second siguiriya style attributed to ‘El Mellizo’ is believed to have possibly been popularised in the 1880s, when the singer from Cádiz was about thirty years old. This composition is another example of his originality and creative capacity. It is a style that has all the musicality and drama we are so familiar with in Enrique’s work.

Luis Soler Guevara and Ramón Soler Díaz commented on this style:

‘The mere fact of having recreated this cante is more than enough reason for his name [Enrique ‘El Mellizo’] to have gone down in the history of flamenco in letters of gold. It is certainly no exaggeration to say that this cantaor gitano is one of the fundamental pillars upon which many styles of flamenco singing are based: soleares, siguiriyas, tangos, malagueñas, romances, saetas and alegrías.’1

Antonio Mairena does a masterful interpretation of this style: External audio link

Dinero.

Ay dinero,

ay dinero,

ay dinero:

Dios mío dinero;

para yo pagarle y a esta gitana buena

aaaa yyya yyyy todo lo que yo le debo.

Money.

Oh money,

oh money,

oh money:

My God give me money

to pay this good gitana

Oh oh oh, everything I owe her.

Enrique ‘El Mellizo’ had a revolutionary capacity to turn folkloric music into flamenco, modernise it and above all, endow it with musicalidad gitana, or Roma musicality. In this way, the form known as malagueñas, a regional variety of fandango, became part of the flamenco singing repertoire with a newfound richness and depth. Many people detect roots from Gregorian chants in ‘El Mellizo’s’ malagueña compositions.

No matter how you look at it, he created a school for interpreting for this cante, and generations of singers, men and women alike, continued to develop it in the same spirit. There are two types: the malagueña doble and the chica.

Here we can hear them superbly interpreted by Sernita de Jerez: External audio link

As stated above, the creativity displayed by Enrique ‘El Mellizo’ marked a turning point in the history of flamenco. This is also the case with the tientos, a palo or musical form, which he transformed by adding a Roma musical touch, removing the folkloric association and creating a model that remains in the repertoire of today’s flamenco singers.

The great Pastora Pavón was one of the best performers of this style.

In this sample we can hear Pastora Pavón's ‘El Mellizo’ tientos: External audio link

In the same way, Enrique modernised cantiñas from Cádiz and gave them a Roma twist in his own characteristic manner, making them slower, more majestic and rhythmic.

Here you can listen to Aurelio Sellés singing in the style of cantiñas de Cádiz: External audio link

Lastly, we have the saeta, a form which ‘El Mellizo’ also modernised; here too he is a key figure in its progression to its current state. His contribution consisted of adding a flamenco touch to what had once been a popular liturgical song. In time it would disappear as such, making way for the new version to emerge.

Manuel Torre recorded this form in the old style: External audio link

Rights held by: Gonzalo Montaño Peña (text) — Estela Zatania (translation) | Licensed by: Gonzalo Montaño Peña (text) — Estela Zatania (translation) | Licensed under: CC-BY-NC 3.0 Germany | Provided by: RomArchive