Often the musical (and cultural) legacy of gitanos flamencos1 is named after their hometown, so it seems to be part of the local popular heritage – but this can be very misleading.

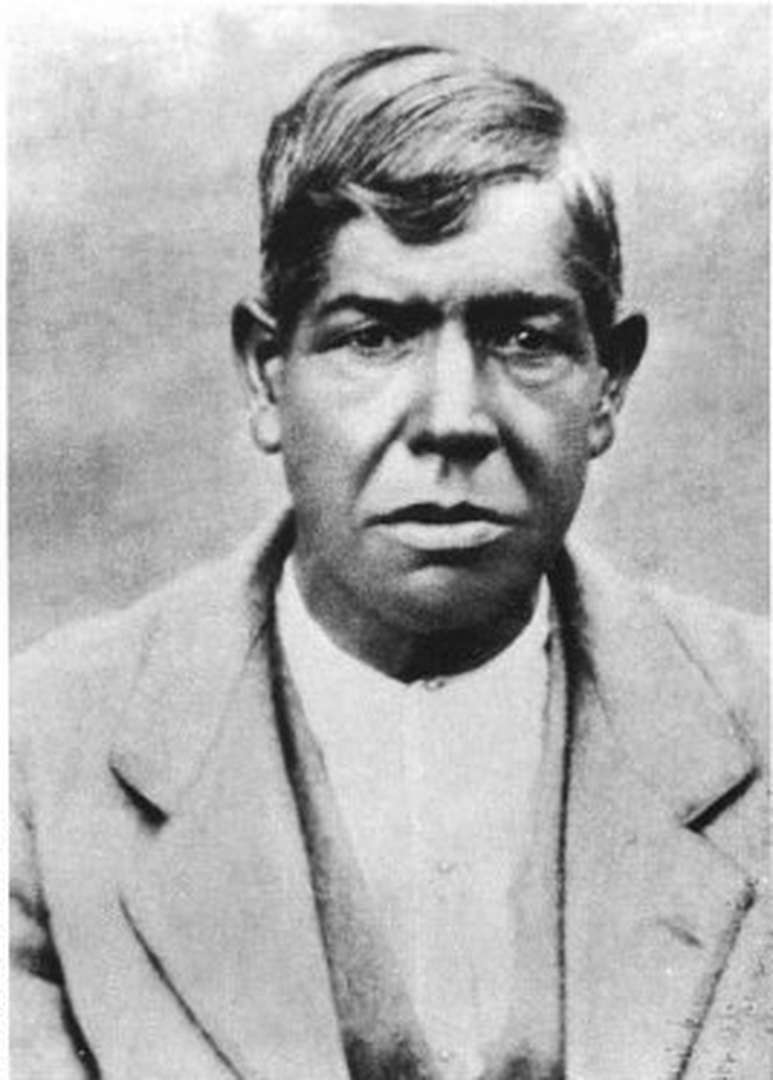

Joaquín el de la Paula and the Soleá de Alcalá

An example of this is known as soleá de Alcalá, a compendium of Roma flamenco melodies that constitute a treasure of great musicological and ethnographic value. The name might lead us to believe that these melodies and customs are practiced by the population as part of their own identity and culture, when the reality is that traditional gatherings to sing these songs have been cultivated almost exclusively by a small group of Spanish Roma families, for whom these cantes2 form part of their everyday vocabulary.

There is one key figure in the creation of these cantes as we know them today: Joaquín Fernández Franco, known as ‘Joaquín el de la Paula’. The genius and musical ability of this Roma is the source of soleá de Alcalá, which was formed not only by the contributions of Joaquín himself but also by other relatives such as Agustín Talega, Juan Talega and La Roesna.

Joaquín Fernández Franco was born in 1875, in Alcalá de Guadaira, Spain, near the city of Seville, in one of the caves that surround the castle. It was in this area of town that the local Roma lived, immersed in economic misery. Some years prior to that, moreover, some of the caves had been populated by a series of Roma families from Triana.3 This coexistence would be fundamental for the creation of these cantes from Alcalá.

‘He picked up something that was closer to folklore. He embellished the phrases, granting them solemnity and drama in the interpretation. He slowed down the rhythm and added details of other Roma cantes from Triana, giving rise to a more elaborate expressive discourse.’

Joaquín de la Paula did not dedicate himself to singing professionally, but he had the creativity and intuition of a professional musician. These were skills that he used to transform the musical elements all around him: he picked up a type of local soleá4 that was closer to folklore and was more suitable for dancing to, then enriched it by giving it his personal stamp. He embellished the phrases, granting them solemnity and drama in the interpretation. He slowed down the rhythm and added details of other Roma cantes from Triana, giving rise to a more elaborate expressive discourse. In general it could be said that his reinterpretation created an almost new kind of music: la soleá by Joaquín el de la Paula.

In general, a cycle or tandem in the soleá style consists of three phases: one as an opening or exposition, a second for the transition and a third for the resolution in which it ends ‘bravely’ or reaches the highest registers.

We can see Joaquín el de La Paula linking three of the cantes that are attributed to him. Separately these cantes have great musical value, but by joining them they take on their complete meaning:

Joaquín’s first melodic style, or beginning, has remained in flamenco as a prototype of a melody to start a cante. Although there are other starting melodies, this is undoubtedly the most commonly interpreted. The great solemnity, expressivity and linearity allow the singer to prepare his voice for the following melodies.

We can hear an example sung by Juan Talega: external link

A ¿A quién le contaré yo

B la fatiguita que estoy pasando

B fatiga que estoy pasando

B la fatiguillita que estoy pasando?

C se la voy a contar a la tierra

D cuando me estén enterrando

C se lo voy a contar a la tierra

D cuando me estén enterrando.A Who will I tell

B of the fatigue that I’m going through,

B the fatigue I’m going through,

B this bit of fatigue I’m going through?

C I will tell it to the earth

D when they bury me

C I will tell it to the earth

D when they bury me.

Then we would have the second cante or melodic style. Here we find a melodic and emotional rise that is not yet extreme but serves as a transition towards the climax reached in the third phase.

Now let’s listen once more to Juan Talega, Joaquin el de la Paul’s nephew, who besides Antonio Mairena is the person who did most to spread this cante:

See external link.

A (Dices) que no me querías

B cuando delante tú me tienes

C el sentido te varía.A (You say) you did not love me

B when you have me there before you

C you change your mind.

With the third melodic style we conclude the series of soleares, making way (normally after a guitar solo) for a new cycle.

This third melodic style exposes all the emotional force that has been channelled into the previous two. This cante is difficult to perform because to convey its expressive sense properly you have to first go up and then down both in melody and in volume, yet without the cante sacrificing any emotion.

The great cantaor Perrate de Utrera gave a masterly interpretation of this in 1962: link.

A Al rezarle al Cristo un credo y a re-

B -ezar al Cristo un credo

C por decir, »Creo en Dios padre«,

D dije, »Gitana te quiero«

C y por decir, »Creo en Dios padre«,

D dije, »Gitana te quiero«.A As I prayed a creed to Christ and pr-

B -raaayed a creed to Christ

C to say, ‘I believe in God the Father’,

D I said, ‘Roma woman, I love you’

C and to say, ‘I believe in God the Father’,

D I said, ‘Roma woman, I love you’.

However, the cante de Alcalá was not limited to Joaquín el de la Paula, for a series of melodies originated within his family that are also related to each other, comprising the musical heart of this flamenco gitano.

In particular we can highlight Agustín Talega, Joaquín’s brother and the father of Juan Talega.

It is the voice of Agustín Talega we hear in this recording: link.

Juan Talega himself recreated another style from the elements within the family, we see the similarities with the previous style, which was attributed to his father.

See external link.

The cantes of the soleá de Alcalá are a melodic repertoire that constitutes one of the richest sources of flamenco music. Their elegant nature, their emotional quality and their undeniable Roma stamp means that these different styles have always been and will continue to be reference points for singers. Nonetheless, it is important to name those who originated and upheld this expression, honouring their memory as creators of cante flamenco gitano.

Rights held by: Gonzalo Montaño Peña (text) — Rosamaria K. Cisneros (translation) | Licensed by: Gonzalo Montaño Peña (text) — Rosamaria K. Cisneros (translation) | Licensed under: CC-BY-NC 3.0 Germany | Provided by: RomArchive