Manuel soon discovered his love of singing thanks to two people who were influential in his infancy: his father (a non-professional singer) and his uncle, Joaquin Lacherna, who was one of the great siguiriya singers in the history of flamenco.

He started earning his living while still a child, working as a fisherman while at the same time taking advantage of his artistic talent to earn a little money. Later on, he began to make his name in private gatherings, then went on to perform in the city’s cafés, where he was billed as ‘El Niño de Jerez’.

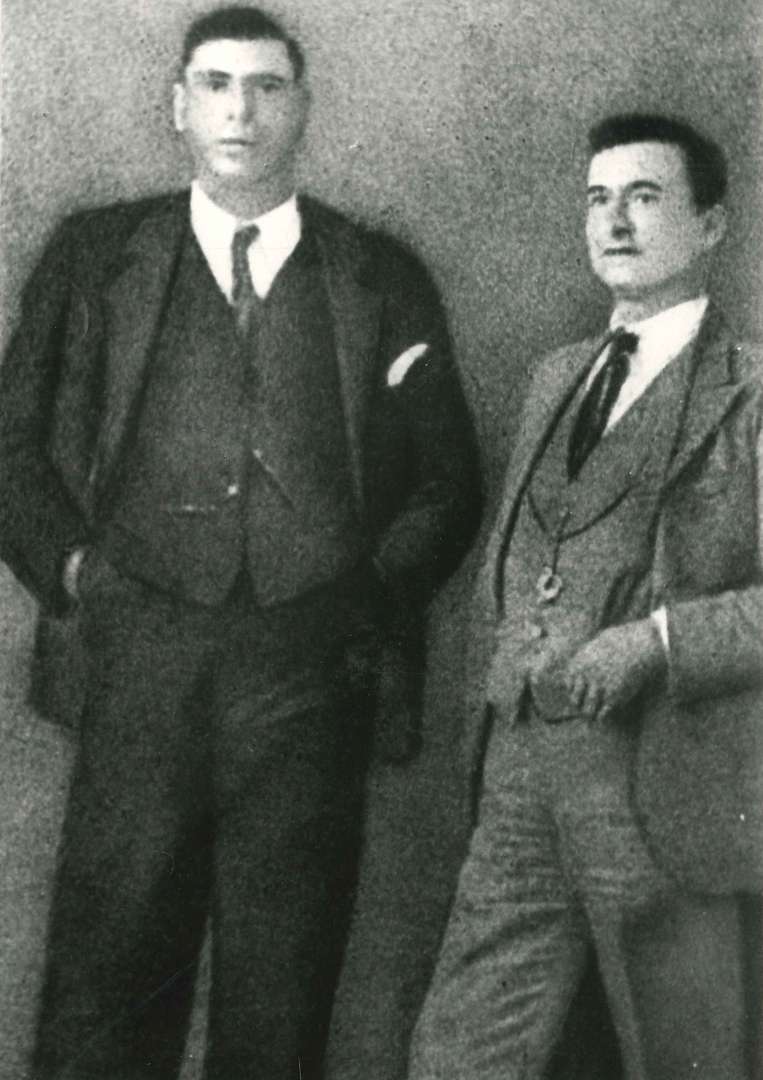

After becoming a cantaor, a flamenco singer in his own right, he decided to turn professional, and so at the beginning of the twentieth century he moved to Seville, where he worked in a variety of flamenco venues while also touring throughout Spain with various companies. He earned the respect and admiration of his fellow artists and left evidence of his art on a number of recordings.

Although flamenco was at this time a relatively recent art form, the burgeoning commercialisation in the middle of the nineteenth century meant that singers received massive exposure on the various stages of the cafés cantantes, and were forced to adapt their respective repertoires to the taste of an ever-growing audience. Gitano song forms were not to the liking of the general public, who were not accustomed to such sounds, and thus they remained a feature of private gatherings of aficionados (and, of course, the Roma flamenco milieu from which they had derived).Some intellectuals, led by Manuel de Falla and Federíco García Lorca, foresaw the danger of this process of ‘folklorisation’ of flamenco, and so they organised a flamenco singing contest in Granada in 1922, with the objective of re-evaluating and rescuing cante jondo. Great artists and intellectuals of the era supported the event and were in attendance. Manuel Torre was presented with great fanfare as a guest artist. As a musician with a tremendous artistic legacy, the singer from Jerez epitomised the Roma cantaor gitano.