The term ‘Balkan’, although sometimes contested because of its ‘orientalisation’ in the European imagination, is widely accepted today in both scientific and public discourse. Thus, when we want to express the idea of common linguistic and cultural features of all communities, we speak of Balkan ethno-culture, the Balkan Linguistic League, Balkan music, Balkan diaspora and also of Balkan Roma groups.

The Romani way of life and culture of Roma in the Balkans were influenced by the Ottoman Empire period, specifically by the impact of Islam and Muslim culture. Roma were present in almost all settlements through the ages and lived in ethnically and/or religiously distinct communities in neighbourhoods called mahalla (in the case of Roma, these were called ‘Gypsy mahala’ by the majority). For centuries they coexisted and constantly interacted with the communities (Turkish, Christian, Jewish, Armenian, etc.) from all the other Mahallas.

As modern independent states, most of the Balkan countries together with their Romani communities experienced similar historical processes: their emergence as ethnic nation states in the second half of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth century; their experience of Soviet-influenced East European communism in the second half of the twentieth century; the post-socialist transition to democracy; war refugee and labour migrations to the West, and endeavours for EU integration.

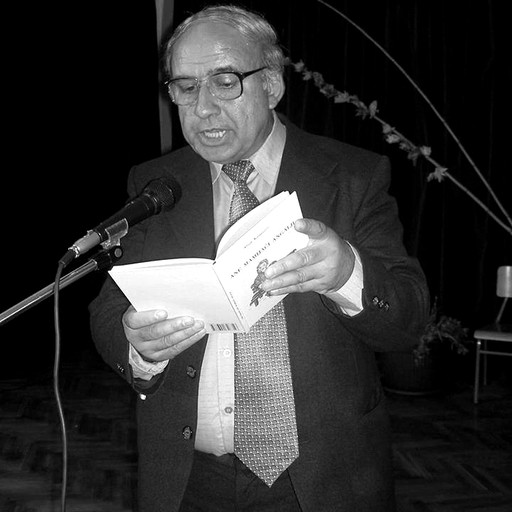

There is a long tradition of well-educated Balkan Romani writers.

The majority of Balkan Roma have led settled lives for many centuries and participated in all socio-cultural processes, historical events and the institutional life of their nation states. During the socialist period many Roma received an education, resulting in a main difference between Balkan (and generally East European) authors and Roma writers from the West. There is a long tradition of well-educated Balkan Romani writers, many of them with university degrees. These authors belong to a certain Romani group, most of them grew up in a Romani mahalla and shared the destiny and values of their Romani community.

This overview covers the period from the mid-nineteenth century to 2017, and the countries considered in detail are Bosnia, Bulgaria, Croatia, Kosovo, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia and all other state formations in which these countries were included historically (e.g. the Ottoman Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia).

Neither young nor undeveloped

The history of the development of Balkan Romani literature goes against the mainstream view that sees Romani literature as a ‘young’, ‘undeveloped’, ‘belated’ or unparalleled phenomenon. Indeed, the transition from the oral to the written form of Romani language took place later than for most other European languages, although Roma in the Balkans were themselves already calling for a written language in the nineteenth century. Despite the fact that these demands were far from being realised, they are a sign that processes among the elites in Romani communities were greatly influenced by general developments in the region in which they lived, since this was the period when endeavours towards national emancipation began, i.e., the elite-led formation of nation states for ethnic communities living on the territory of what was then the Ottoman Empire.

In this regard we should mention that the first Romani literature texts in the Balkans were folklore material, repeating the well-known pattern of ethno-national states in nineteenth-century South-Eastern and Central Europe. They followed the Herderian model of national emancipation through the collection and publication of a wide range of folklore material, dictionaries, narratives about customs and traditional songs representing the national spirit. Thus, in earlier historical periods, collections of Romani folklore appeared parallel to folklore collections of the respective ethno-national states.

Thus, the development of Romani literature repeats the pattern whereby European languages transformed from oral to written languages.

Take, for example, the Romani folklore tales collected and published by Barbu Constantinescu in Romania in the late nineteenth century or Naiden Sheitanov’s records of the Sofia Erli dialect in Bulgaria in the first half of the twentieth century. Very often the same people, such as, for example, the Bosnian scholar Rade Uhlik, collected and published Romani folklore and made Romani translations of Bible texts. Thus, the development of Romani literature repeats the pattern whereby European languages transformed from oral to written languages – here the first corpuses of written texts were folklore narratives collected and published by folklorists and translators of Bible texts into Romani.

The development of Balkan Romani literature might be called belated only if we compare it with the written traditions of the communities and languages that already had their own nation state. However, compared with the written culture and literary development of other state-less ethnic and linguistic communities in the Balkans (such as the so-called Aromanians or Vlachs, Istro-Romanians, etc.) or in other parts of Europe (the Saami, for example), we see that Romani literature was actually published in a ‘normal’ timeframe. The folklore traditions of all these communities, like those of the Roma groups, were recorded in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, while fiction only started to be written after World War II. Furthermore, we can see how rich and ‘over-developed’ Romani literature appears when compared with the literatures of other Balkan minorities without a national state of their own.