I can still remember the first photos of Sinti und Roma that I perceived consciously in the German mass media. They were pictures of homeless families in the Görlitzer Park in Berlin, which were circulated widely in the press in 2007. I was already 24 years old at the time. Such images of poverty and exoticizing photographs continue to dominate the perception of Sinti and Roma – and media images in turn influence mental images and thoughts. Such images persevere and determine our habits of seeing.

Searching For The Magic Of The Everyday

Andrzej Mirga | No title | photography | Poland | pho_00041 Rights held by: Andrzej Mirga | Licensed by: Andrzej Mirga | Licensed under: CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International | Provided by: Andrzej Mirga – Private Archive

It is 2018. I have been working in the Politics of Photography section of the RomArchive for two years as a white person. During this period, my colleagues and I asked many questions and had many discussions. Who takes photographs? Who photographs whom, and when? Who is photographed? How are they photographed? Who is exoticized or stigmatized by photography? What images dominate the media and our habits of seeing? Who gets complex representation, and who is ignored or represented one-sidedly or wrongly.

“No shot you take is innocent.”

For more complex and realistic images of the multifaceted reality of the lives of Sinti and Roma, we must question racist, discriminatory and exoticizing habits of seeing. Vicente Rodríguez Fernández, co-director of the Legacies of Empires program at the University of Washington says, referencing Jean-Luc Godard: “No shot you take is innocent.” All photos are taken in a social context. In the case of Sinti and Roma, this is a context of centuries-long marginalization, stigmatization, discrimination, exoticization and persecution.

We need to (want to) understand this context from other perspectives, which can be a painful process. This can mean unlearning putative knowledge, changing deep-seated positions and opinions and constantly grappling with violent mechanisms. In an interview1 Rodríguez Fernández explains how this process of unlearning and re-learning2 can work:

“I think maybe what people want to say by ‘decolonizing images’ is to learn to understand, to decode, the images that have been designed by power in a way that empowers and gives voice to the people that appear as passive subjects in the pictures. Usually racialized people, women, minorities.”

Rodríguez Fernández

In the course of our work, we asked ourselves what images of Sinti and Roma are missing from the public sphere, and set out to look for them. There is a lack of everyday pictures, family pictures, pictures of friends spending time together. There is a lack of images of workers, artists, academics. There is a lack of pictures which do not exoticize, stigmatize, or exercise violence in some other manner. There is a lack of pictures taken by Roma and Sinti. Personally, I find that there is a lack of pictures of my friends and people similar to them, who would not fit into that report about the homeless families in Görlitzer Park. Filling this gap can contribute to changing our mental images and representations.

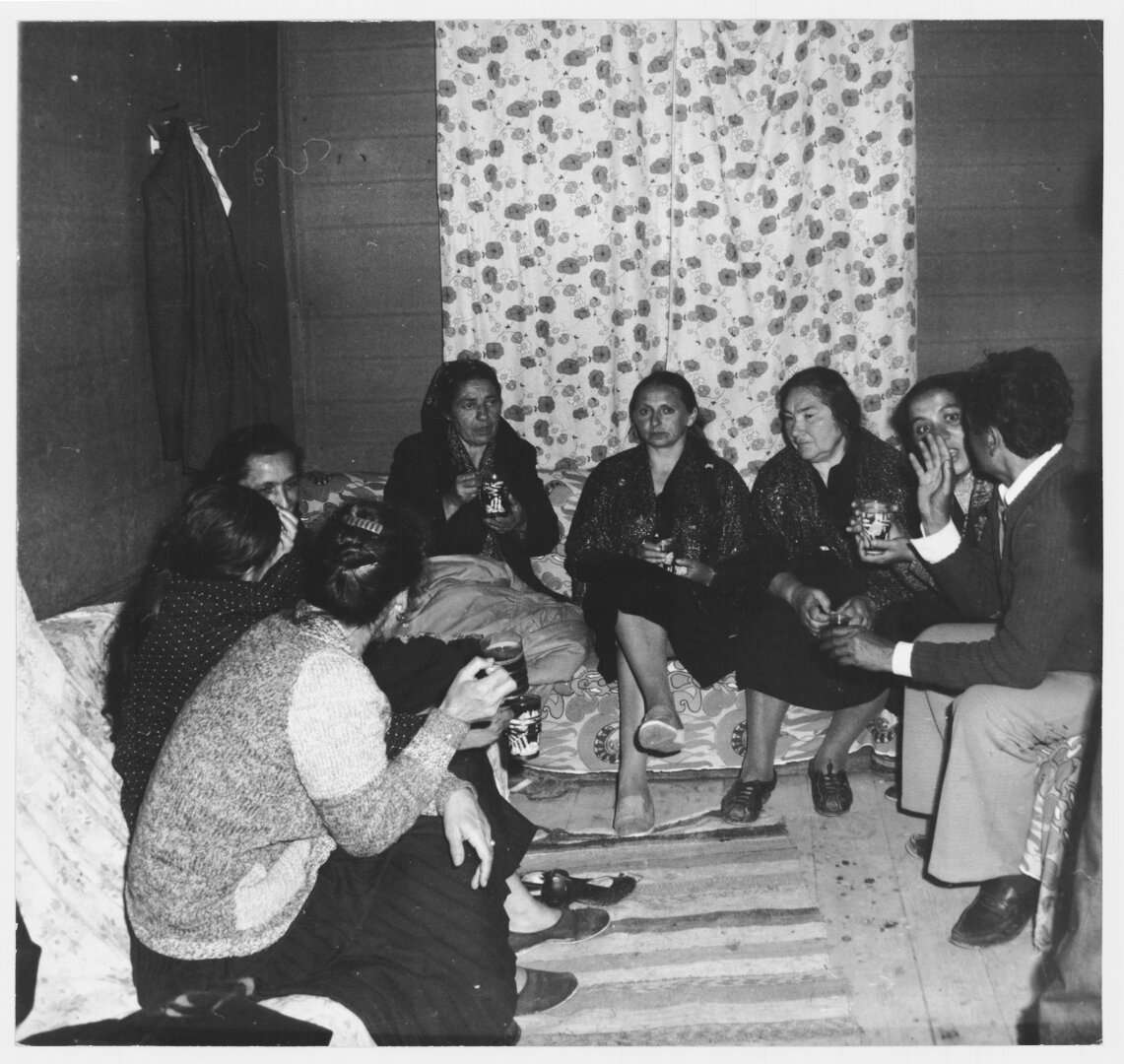

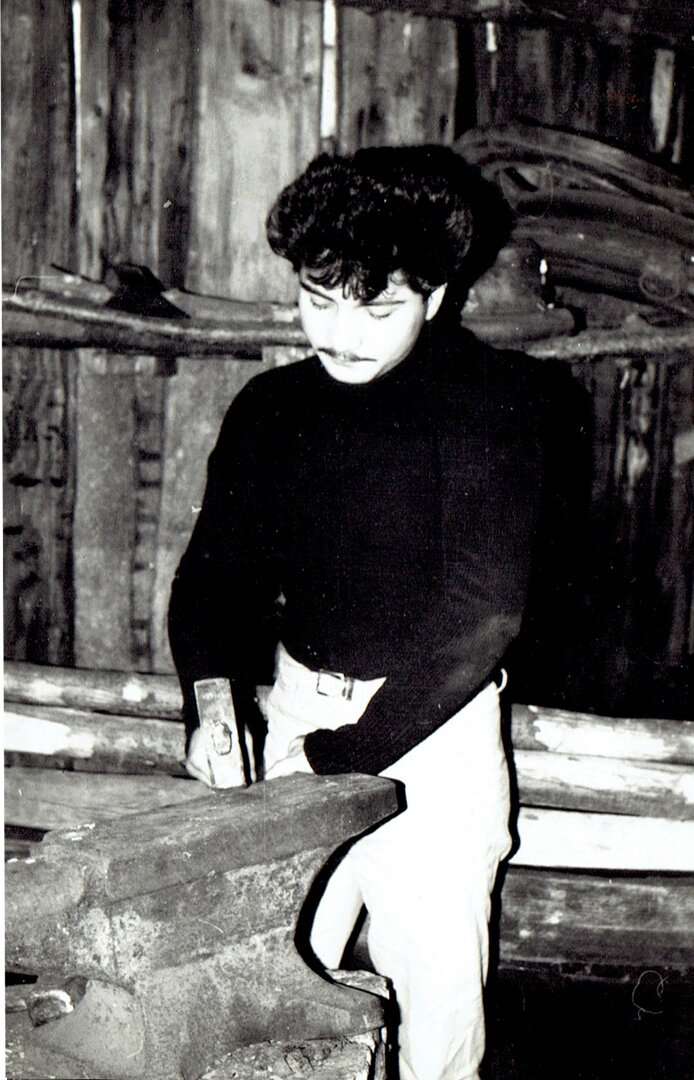

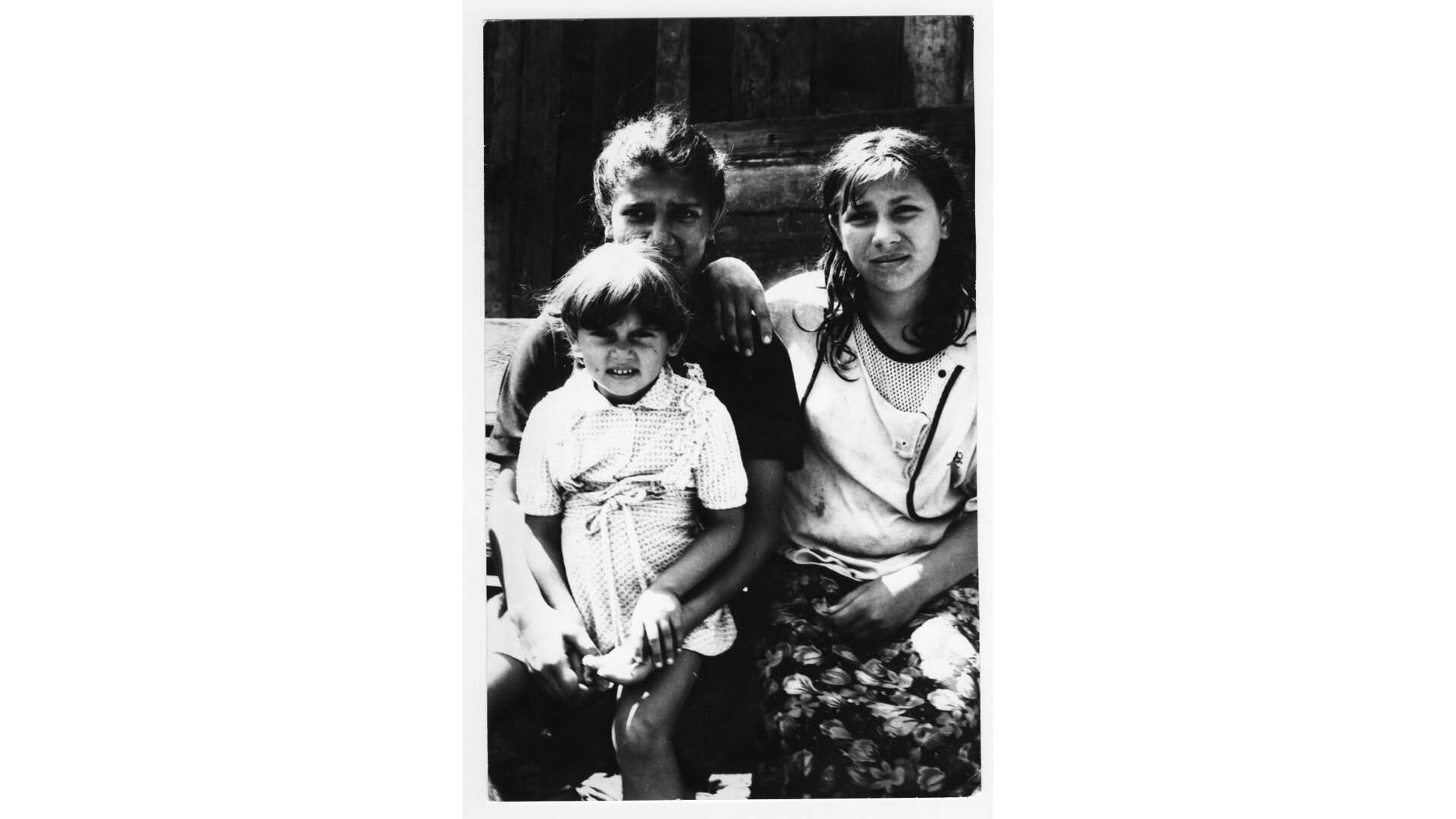

In the course of our search for these missing pictures, Anna Mirga-Kruszelnicka brought to our attention the photographs of her father. Andrzej Mirga is a Roma man from Czarna Góra in Poland, who now lives in Kraków. Prompted by his ethnology studies at university, Mirga began to document his own family life, taking photos of important events in the villages of Czarna Góra and Szaflary, Poland and encounters with a theater group called Gardzienica towards the end of the 1970s. These photos lay forgotten among other documents for many years, until his daughter Anna rediscovered them when she was still at school.

“This is part of our history. Our family.”

“As a young scholar, I was interested in documenting things about us, as family life. There are some pictures of ceremonies like funerals, which are very private. I was very much aware what the value, both archival and historic, of a picture is,” Andrzej Mirga said when I asked what motivated him to take these photos. “They show a world that has changed a lot since then,” Anna Mirga-Kruszelnicka adds.

Yet what is it that differentiates these pictures from other anthropological photographic documentation of Sinti and Roma? Mirga himself points to a key difference between his gaze, his photographs and other anthropological pictures of Sinti and Roma:

“Not every picture is a good picture and not every picture is a good document. From the past I think it is good to have some pictures taken by Roma, because it brings a different perspective, also including our emotions towards these pictures, because we know the people, we know the situations when these pictures were taken, so we have certain emotions that are tied to these kinds of pictures. This is part of our history. Our family.”

Andrzej Mirga

Exactly this change of perspective, and the emotions wrapped up with them, are what interest me.

If I understand the emotions that an image provokes, I can feel the same emotions, empathize more easily – just like in personal interactions. Those photographed trust Mirga, the photographer – and us viewers – enough to reveal some facets of their everyday lives, enabling us to take a mental trip to their homes. Trust is a political statement, a call to look beyond clichés and make a more realistic image for ourselves.

How can we tell complex (visual) stories about Sinti and Roma without ethnicizing them?

When I show Mirga's photos to Anna Daróczi, the coordinator of the Phiren Amenca volunteer program in Budapest, her spontaneous questions are: “Do people want to see this? Are they interested if it is not something exotic? I am just wondering because these are family pictures, like everyday pictures of a community, most of them. How can you tell that those people are Roma? And is that important?” Daróczi's associations and questions are relevant to more than just these pictures; they have accompanied our project over the past few years. How can we tell complex (visual) stories about Sinti and Roma without ethnicizing them? Do these images hold potential for identification – for Sinti und Roma, and perhaps for all others, due to their universality? Can we perhaps, by showing such images, create spaces in which Sinti and Roma are represented in a realistic and complex manner?

Anna Mirga-Kruszelnicka – an anthropologist, activist and RomArchive curator – notes that it is a specific aspect of her first encounter with the photos that makes them so special to her:

“I was very excited when I found the pictures. I was struck by the intimacy in them. Because a lot of people in those pictures are not just people, they are cousins, friends, family members. They know my father. And the context in which he took many of the photographs was when he was going to settlements with this theater project and they were doing theater workshops and it was kind of playful, but also about learning, bringing in people from the outside [...]. For me, what strikes me is this kind of intimacy that you can see in some of the pictures. You can see it in the way some of the subjects are looking, the expressions in their eyes or in their faces, that they are really comfortable and are just having fun. So this is something that for me communicates that intimacy and it's also something that you don’t always see. Because these people, they are posing, of course, but they feel very comfortable doing so.”

Anna Mirga-Kruszelnicka

The everyday scenes in the photographs of Andrzej Mirga also inspired his niece, the artist Małgorzata Mirga-Tas, who lives in Czarna Góra, in making some of her own paintings. “Her paintings bring out the magical realism that is hidden behind these kinds of everyday things,” says her cousin Anna Mirga-Kruszelnicka. And if we look closely, we find the magic of the everyday and the invisible in the photos, too.

Rights held by: Astrid Oelpenich (text) — Agi Bezeczky (translation) | Licensed by: Astrid Oelpenich (text) — Agi Bezeczky (translation) | Licensed under: CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International | Provided by: RomArchive