The history of Romani political activism is traditionally narrated from a heterosexual, masculine perspective, with the role of men being magnified, whilst the accomplishments of women and of people of differing sexualities, becoming a rather diminished, or even invisible matter. Until recently, gender was an analytical tool to particularly examine the participation of Romani women in political activism, and the Romani civil rights movement.

The Building Blocks of the Romani Women’s Movement in Europe

Through the history of Romani political activism, it can be seen that gender, race, ethnicity, class, and sexuality, are systemic intersectional forms of inequality that influence the structure of activism and representation, in addition to models of social advantage and disadvantage, identifying groups based on their social location. In this conceptual framework, not all Roma are equally oppressed and not all Roma activists are equally recognized; rather Roma are located within a multidimensional social order. This essay recognises the engagement of and contribution to political thinking, by Romani women and LGBTQIA activists, through revising the record of their involvement in the struggle for Romani emancipation.

An account from the early twentieth century shows how ‘Gypsy’ women in the UK, angrily resisted evictions in October 1904, in Birmingham, by throwing children in front of the horses and the Gypsy wagons, and even ‘...dared the drivers to trample on them’.1 In this period, Romani organisations were rarely established by, or led by Romani women; they are either erased, or remain ‘hidden from history’2 deemed (by male authors) insignificant in the narration of political emancipation.

Romani Women and their early activism

The most important Romani political activism in the 1920s and 1930s happened in Romania and Poland. In Romania in 1933, there was an attempt to unite all the Roma in the country, into two political organisations: the General Association of the Gypsies in Romania and the General Union of Roma in Romania. In some key posts, the General Union... appointed Romani women; for example, the regional branch of the General Union in Sibiu elected a female honorary vice president.3 On 8th October 1933, in Bucharest, under the auspices of the Union... led by G. A. Lazareanu-Lazurica, a congress was organized involving over 200 participants4 proposing a separate female branch of the Union... that would educate and support Romani women. Moreover, the delegates requested that literate women should have the same rights as men had in the Council of Elders, subject to future regulation.5 In 1933, this idea was considered very progressive, in the context of the struggle to achieve equal rights for women in Europe (Romania granted women voting rights in 1946). Klimová Alexander also suggests (though based on uncertain and speculative, secondary sources), that in Western Europe the only independent Romani organisation created during the inter-war period, was the Panhellenic Cultural Association of Greek Gypsies by two Romani women in 1939.6

Romani Women during the Holocaust (1939–1945)

Why is it relevant to deal with Romani women’s experience during the Holocaust? Nazi ideology targeted both Jewish and non-Jewish, Roma and Sinti communities; however, some of the actions specifically targeted women. German physicians and medical researchers used Jewish and Roma and Sinti (described as ‘Gypsy’) women, as subjects for sterilization and other unethical human experimentation.7 Anna Szász has analysed a number of individual testimonies from Roma and Sinti women, of their experiences during the Holocaust, who practiced different forms of resistance. She puts it succinctly:

‘The will to survive, putting the preservation of community at the centre-point, constituted the fundamental resistance [...] Their resistance was not exclusively a fight for life, but also small sets of activities motivated by a conscious attempt to defy the Nazis and thwart their goal of depriving “Gypsies” of their humanity...’8

Ceija Stojka, an Austrian-Romani woman, survived the Romani Holocaust, but these unforgettable experiences become a dominant narrative in her work as a writer, painter and musician. Alfreda Noncia Markowska a Polish-Romani woman who also survived, saved approximately fifty Jewish and Romani children from death, during the Second World War.

Romani Women: Activism and Resistance between 1945 and 1989

After 1945, the development of Roma political activism was fragmented. Very few Romani women had a chance to become visible in a male dominated field. Hungary was one of the countries where Romani women came to the fore, leading a Roma organisation that was partly a state institution. Michael Stewart9 argues that Hungary was the only country in socialist Central Europe, which envisioned the contribution of Roma representatives, to the development of policies improving opportunities and the living conditions of Roma. In 1957, Mária László (b.1909–d.1989), received a mandate from the government to establish the Hungarian Gypsy Cultural Association (HGCA) (Magyar Cigányok Művelődési Szövetsége) being the first Romani woman to lead such an association. Although her leadership as Secretary of HGCA was short-lived (1957-1958), László became a very ardent and effective leader, providing political, economic and administrative support to Roma co-operatives (mainly involved in steel production and nail-making). She turned the HGCA into an organisation that represented the rights of Roma, though she became a victim of her own success when the government terminated her position on a pretext. However, she paved the way for broader Romani emancipation and remained a source of inspiration for several Romani intellectuals who challenged the racist discourse on Roma and the politics of state socialism, from the late 1970s onwards.

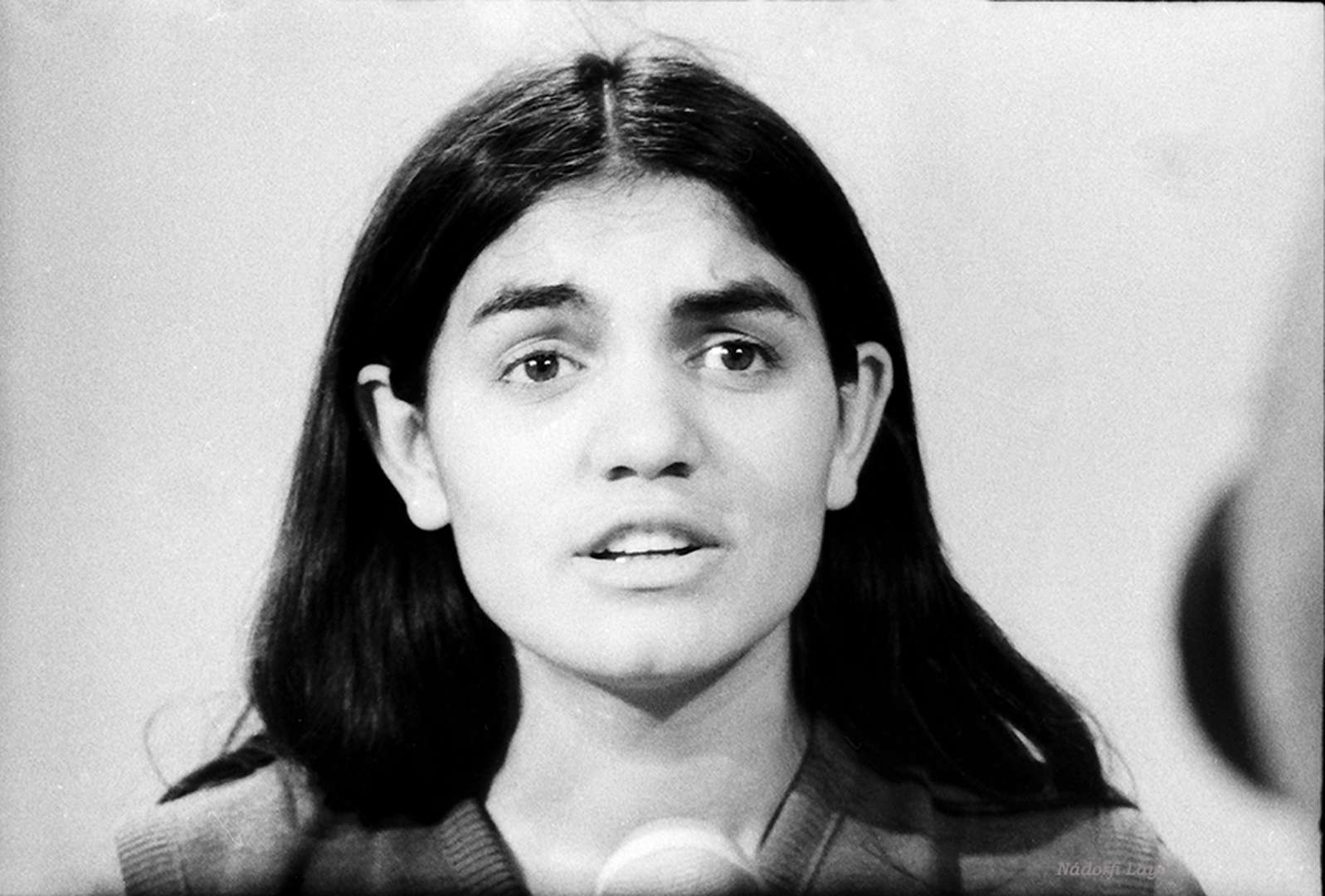

Ágnes Daróczi (b.1954), was one of the oppositional leaders under state socialism and became an iconic figure in the fight for the recognition of Roma. While Mária László remained a Hungarian Romani leader, Daróczi was able to transcend national borders, building a transnational profile and a Roma solidarity network. She achieved national recognition as a seventeen-year-old in 1972, via a talent show (Ki mit Tud?) for reciting a poem in the Romani language by Romani poet, Károly Bari,10 advancing Romani identity and political consciousness, in an era when official discourse depicted Roma as a ‘social problem’. Daróczi was also involved in international Romani politics, and was invited to the Third World Romani Congress at Göttingen in 1981, where she was one of the very few Romani women out of 300 delegates from twenty-two countries.11

During this period, there were a few other Romani women emerging in different European countries, who later became role models for future generations. Nadezhda Demeter, the Romani ethnographer, wrote her dissertation in 1988, which was based on a Soviet ethnographical approach and on a limited Soviet policy discourse that divided Roma into two groups: assimilated and nomadic.12 Despite this, being a Romani ethnographer in Soviet academia was still considered an enormous achievement. Katarina Taikon-Langhammer (b.1932–d.1995), was a Swedish Romany activist, leader in the civil rights movement, writer and actor, from a Kalderash family. In 1953, the sixty-year government ban on Romani immigration to Sweden ended and Taikon became an advocate for those Roma seeking refuge in Sweden. Concomitantly, she recognized that the only way to end prejudice against Roma in Sweden was to educate young people and began to write her popular series of children's books, based upon her own childhood, Katitzi. A Swedish TV-series, drawing upon the books, was produced in 1979.

Fighting for Romani women’s rights (1989-2005)

After the ending of the ‘Cold War’, the early 1990s brought new hope and enlarged perspectives for women’s rights in general. Women’s equality and feminist ideas (particularly in post-communist countries), became the most contested and challenging issues.13 These ideas, theories and practices had already been developed in western European countries in the early 1970s, but had not had any impact on Romani women’s activism, until the early 1990s.

In 1990, the Gitanas movement (political and social action by Spanish Romani women), was the first to emerge. The Gitanas distinguished themselves both from the male-dominated, Spanish Romani movement and from the Spanish women’s movement, which sought to integrate them. On the one hand, they aimed at dismantling ‘machismo’ and patriarchy, while on the other, they challenged the historically rooted, gendered antigypsyism, which the Gitano community had suffered for centuries.14 Although several Romani Gitana women, such as Rosa Vázquez or Adelina Jímenez, were already engaged in civic and political activism, the first Romani women’s association in Spain, Asociación de Mujeres Gitanas Romí, was established in Granada, 1990. In June of that year, Romí organized the first seminar dedicated to the situation of Gitano women in Spain. The Gitanas movement consists of activists as well as scholars, such as Ana Giménez Adelantado, who became the first Gitano, female professor in Spain.15

Meanwhile, in several post-socialist countries, Roma political activism was given important momentum through Romani civic organisations, political parties and Romani candidates, who participated in national elections. One of the first explicitly Roma women’s organisations was established in Hungary in 1991, the Gypsy Mother Association, led by Ilona Zambo.16 She explains,

‘The idea came from having been part of a Roma dance group [...] I was very surprised to hear about the traditional pressures on Roma women and what they had to live with. Many Roma organisations were forming around that time, but none were for women [...] Bela Osztojkan, who was a Roma leader, called me the first Gypsy feminist for standing up for the rights of Roma women. He did not mean it as a compliment...’17

Similar to Ilona Zambo, Sylvia Dunn, established the National Association of Gypsy Women (NAGW) in the United Kingdom, which offered protection for Gypsy and Traveller women who suffered harassment, both by police and local authorities, in 1994. Sylvia Dunn stated that her newly founded association would strengthen women's resistance,

‘They think that getting us into houses will be the end of us. They had better think again. We are not going into houses. Why break up families by putting our men into prison, and our children into care? We are being criminalised for being Gypsies. It's ethnic cleansing. It will turn women mad...’18

Sylvia Dunn resisted British discriminatory legislation and struggled for gender equality in international Romani representation; at the Fifth World Romani Congress in Prague (2001), she suggested that instead of having one representative from each country who were usually men, there should be one man and one woman, to enhance gender equality.19 She also stood as a candidate in the parliamentary elections of 2004.

In addition to NGO activism, Romani women also became visible through parliamentary elections during the 1990s. In the 1990 elections in Czechoslovakia there were several MPs who identified as Roma. Klara Samková,20 a pro-Roma activist who did not identify herself as Roma, publicly associated herself with the most significant Romani political party, Romani Civic Initiative (ROI). Anna Koptová was elected as a representative for the People against Violence (VPN); After the dissolution of Czechoslovakia (1993), Monika Horáková was elected to the Czech Chamber of Deputies, by the Freedom Union (US), as one of a new generation of Romani political activists in 1998. In 1990, after the first democratic elections held in Hungary, the liberal party SZDSZ, offered two Romani people the opportunity to be elected as Members of the National Parliament, one of them being Antonia Hága.

Romani women were appointed to high positions in various governments. In Slovakia, Klára Orgovánová was an advisor to the Slovak Government from 1991 to 1993; in 2001 she was appointed as a Plenipotentiary for Roma issues. Éva Hegyesiné Orsós became the first and only Romani President of the Office for Hungarian National and Ethnic Minorities between 1995–1998, a governmental institution. Judit Berki was appointed Deputy State Secretary for Roma Integration, at the Hungarian Government (2002 and 2004).

The first European feminist breakthrough for Romani women’s activism was at the Primer Congreso Gitano de la Unión Europea (First Gypsy Congress of the European Union, 18th to 21st May 1994), which took place in Seville. Romani women highlighted the urgent need to address their needs and interests.21 On that occasion, a group of twenty-nine Romani women, from seven countries, issued a joint conclusion regarding the specific problems of Romani women, as well as some recommendations.22 As a result of this Manifesto of Roma/Gypsy Women, the Council of Europe (CoE) organized a Hearing of Roma/Gypsy women in Strasbourg, 20th to 30th September 1995. The Hearing gave recognition to Romani women’s rights and the importance of gender equality in Roma related development programs.

The CoE was one of the first international organisations that began to raise awareness about Romani women, gender equality and youth, in 1995.23 At these early training events, there were several feminist Gitanas from Spain, Amara Montoya Gabarri, and Carlota Santiago Camacho, who were connected to the first Romani women’s organisation, Association de Mujeres Gitanas: Romi. At the training there were several Romani women from Central and Eastern European countries, for instance Angéla Kóczé who later became a frontrunner in theorizing Romani feminism and women’s political activism. As a result of the training for young Roma leaders, organized by the Youth Directorate of the Council of Europe, the Forum of European Roma Young People (FERYP), was developed. Established in 1998, it was the first international Roma organisation led by a Romani woman, Alexandra Raykova.

In June 1998, the Open Society Foundations organised the First International Conference of Romani Women in Budapest in cooperation with the Roma Participation Program at Open Society Foundations.24 Following the 1998 conference, the Roma Participation Program and the Women’s Program sponsored a joint Budapest internship; Liliana Kovatcheva, from Bulgaria, was the first intern in January 1999, compiling a database of Romani women. At the same time, the Women’s Program granted a fellowship to Nicoleta Bitu to participate in the Advanced Leadership Training for Women program. In the same year 1999, Bitu raised gender issues and concerns related to the Roma communities, at a meeting of the Specialist Group on Roma/Gypsies, of the Council of Europe. In 1999, a milestone in the Romani Women’s Movement was passed, when Bitu’s report25 on Romani women was supported and adopted by this group.

All these important events stimulated the first informal network of Romani women, which later became more formal, with a horizontal collaborative leadership consisting of Nicoleta Bitu, Azbija Memedova, and Enissa Eminova, in 1999. The Romani Women’s Initiative (RWI) operated from 1999 to 2006 with the support of Debra Schultz, feminist historian and founding Director of the OSF Women’s Program. She has described their collaboration in creating the Romani Women’s Initiative (RWI), ‘...as an unprecedented collaborative experiment in intersectional feminist practice, that operated at local, national, and transnational levels’.26

The Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) became another key player in promoting Romani women’s rights, holding Supplementary Meetings in Vienna (14th to 15th June 1999) that were dedicated to gender issues. Later, at the OSCE Supplementary Human Dimension Meeting on Gender Issues (September 1999, Vienna), it was decided that a gender component should be included on the agenda for the following meeting.

Meanwhile, Romani women participated in mainstream international meetings, such as at the Beijing Plus Five meeting in New York (2000) and at the UN World Conference against Racism in Durban, South Africa (2001), where Romani women raised issues such as forced sterilisation, structural violence and domestic abuse. At the Durban conference, the Center for Women’s Global Leadership (CWGL), at Rutgers University held a hearing on Racial and Sexual Oppression, to introduce women’s voices and feminist intersectional analysis to a global discussion on racism.27 Roma women activists, Slavica Vasić and Vera Kurtić of Serbia, were an integral part of the video produced by CWGL; ‘Women at the Intersection of Racism and Other Oppressions: A Human Rights Hearing.’ (12:13-15:20 video footage)28 Kurtić testified that ‘...the international community has ignored the facts about the rape of Roma women in Kosovo and the trafficking of women, amongst whom, great numbers are of Roma ethnicity.’ Arguing that few women ‘around the globe’ receive adequate support and justice following being raped, given the tendency to blame victims, Kurtić went on, ‘Therefore you will understand the kind of situation a raped Roma woman is faced with.’29

In February 2003, with the assistance of the Council of Europe, Romani women activists from eighteen European countries launched the International Romani Women’s Network (IRWN) with an older and more traditional leadership, than the Romani Women Initiative (RWI), that included Ágnes Daróczi, Leticia Mark, Miranda Vuolasranta. The participants elected a temporary coordinating committee and adopted a Charter. Soraya Post, representing the Romani and Sinti communities in Sweden, became President of IRWN.30 IRWN was a member of the leading European women’s rights umbrella organisation, the European Women’s Lobby, from 2004 to December 2007. Leticia Mark in collaboration with Enikő Vincze in 2009 started a trailblazer Romani feminist journal, called Nevi Sara Kali.

In European Parliamentary elections in Hungary, two Romani women were elected as Members of the European Parliament (MEP) in 2004. The first, Lívia Járóka, was elected from the right-wing Populist Party FIDESZ and the second Romani MEP, Viktória Mohácsi, replaced another Hungarian MEP.

Romani Women’s Movement and the Decade of Roma Inclusion 2005-2015

The Roma Women’s Forum was held on 29th June 2003 in Budapest, organised by the Open Society Foundations Women’s Program, the forum brought together more than one-hundred Romani activists, donors, international human rights activists, with government representatives from Europe and the United States. At the Forum, Romani women presented their own comprehensive policy agenda to high-level officials from regional governments and international agencies. Interestingly, the forum took place the day before a related, two-day conference, ‘Roma in an Expanding Europe: Challenges for the Future’, which launched the Decade of Roma Inclusion (2005-2015). Disappointingly, the Forum was not officially included in the larger high-level conference, hosted by the Hungarian government and co-sponsored by the World Bank, the Open Society Foundations (OSF) and the European Commission. Nevertheless, at the conference of Prime Ministers from nine EU-accession countries, James Wolfensohn, the World Bank President, praised the leadership of Roma women and young people; yet Romani women leaders were not treated equally, nor invited to make high ranking decisions. To ensure that Roma women’s issues would be integrated into the Decade of Roma Inclusion, Nicoleta Bitu presented a summary of the Roma Women’s Forum agenda, to these Prime Ministers. RWI hoped that this international support and visibility would position it as a leading contributor, as the Roma community partnered with donors and policymakers to implement the Decade... strategy from 2005-2015. NWP published ‘A Place at the Policy Table: Report on the Roma Women’s Forum’,31 to disseminate the ideas generated at the Roma Women’s Forum.

Whilst efforts to integrate gender in the strategy and implementation of the Decade..., as well as throughout the Romani Civil Rights movement, were slow and disjointed process, the Romani Women Initiatives pushed Romani women’s issues and equality onto the global social justice agenda. In 2005 and 2006, Roma women presented their concerns at the UN Commission on the Status of Women 10th Anniversary Review of the Beijing Platform for Action, at the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) hearings and the European Parliament’s Hearing on Roma Women. At the forty-ninth session of the UN Commission on the Status of Women, Roma women activists sought to keep the momentum going. Addressing practical and conceptual barriers to representing Roma women’s issues in policy forums, Alexandra Oprea, a Romanian born, Romani activist who lives in the United States, called for an intersectional approach to collecting race and gender sensitive statistics, to accurately monitor the situation of Roma women. In June 2006, the European Parliament issued its first, historic resolution on the Situation of Romani Women in the EU Member States, using the research that was produced by Romani women scholars, activists, and policy experts.

Meanwhile in 2006, the OSF Board decided to combine programming on Roma women by the Women’s Program and the Roma Participation Program (RPP), to create a Joint Roma Women’s Initiative (JWRI). The JWRI was staffed by Nicoleta Bitu, Enisa Eminova and RPP’s Isabela Mihalache from Romania.

The OSF’s strategic move unfortunately put an end to the RWI; however, at the same time the Council of Europe sought to leverage Romani women’s concerns and visibility, with the support of several member States. In September 2007, the First International Conference of Romani Women was held in Stockholm, with the support of the Swedish government, a pattern that was subsequently followed at each event. In January 2010, the Second International Conference of Romani Women took place in Athens, Greece; the third international Romani women’s conference was organized in Granada, in 2011. The Fourth International Conference of Romani Women was hosted in Helsinki in September 2013, Finland, whilst the Fifth International Conference of Romani Women was held in Skopje, October 2015, led by Mabera Kamberi. In November 2017, the Sixth International Conference of Romani Women was held in Strasbourg. An impact of these international conferences was the launching of networks; Rowni (Roma Women’s Network, Italy), launched in 2010, is a network of international Romani activists. Phenjalipe (Sisterhood) was launched in 2013, as a result of preparations for the Fourth International Conference of Romani Women.

In the meantime, at the international level, some Romani women filled important positions. In 2011, Rita Izsák-Ndiaye was appointed as the Independent Expert on Minority Issues by the Human Rights Council, Hungary. She was supported by the same right-wing Populist Party FIDESZ who support Lívia Járóka. Mirjam Karoly, became ODIHR's Senior Adviser on Roma and Sinti Issues from 2013 to 2017. From 2016, Miranda Vuolasranta has been the first female President of the European Roma and Travellers Forum.The ‘queering’ of the Romani Women’s Movement was started by several Romani LGBTQI activists; Vera Kurtić is amongst the first who published her book, Džuvljarke: Roma Lesbian Existence, as an explicitly lesbian, Romani account, in 2013. The very first International Roma LGBTQI Conference took place as a part of the Prague Pride festival, 2015. The conference was organized by the Prague-based Romani association, ARA ART32 and included a performance by the Theatre of the Oppressed, followed by a public discussion entitled, ‘Hot Chocolate International – the situation and experiences of Roma LGBT in the World.

Rights held by: Angéla Kóczé | Licensed by: Angéla Kóczé | Licensed under: CC-BY-NC 3.0 Germany | Provided by: RomArchive