From Roma poverty to cultural recognition

The first Hungarian representative survey about Roma was carried out almost a hundred years after the first “Gypsy census”, under the supervision of István Kemény in 1971 and began as a research report. Kemény worked with social scientists (and frequently dissidents), who engaged with the subject of ‘poverty and Gypsies’, such as Zsolt Csalogh, Gabor Havas, and Ottilia Solt. Their research shaped the political agenda of the Roma civil rights movement. The Roma representative survey of 1971, was criticised by Roma intellectuals, in that it exclusively focused upon poverty and did not recognize Roma as an ethnic group with a distinct culture. Moreover, questions of Roma ethnicity and poverty were articulated as exclusive issues, rather than as intersecting categories, with the question framed as one of ‘Gypsy Culture’, or a ‘Culture of Poverty’?

Zsolt Csalogh later reflected on the experience of research in the following way:

“When, in 1971, we conducted the Kemény research, we knew that we were doing subversive work. We experienced taking a stand against the system [...] we were uncovering one of the shocking scandals of the system [...] Of course the primary goal was to help the fallen, the hungry, the impoverished, but it was also very important to be a splinter in the eyes of the system”

During this interview, Ágnes Daróczi reminded Zsolt Csalogh that, in 1978, when he was at a conference in Békéscsaba, he had stood up in the audience and made a demand for Roma institutions, a Roma museum, a theatre, and cultural centres and so on.

However, Kemény’s research made a significant impact on the later representation of Roma in film, photography, and literature. They were depicted as a group that illustrated one of the “failures of socialism”, materially deprived and trapped in generational poverty, a “pariah” underclass who live outside the society in “Othered” unknown collectives. Pál Schiffer was the most productive and prominent of Hungarian film-makers to represent marginalized Roma identified in Kemény’s research. In his iconic 1970 film, Fekete vonat (Black Train) he portrayed the lives and struggles of Roma men as menial, under-educated workers in industry, who travelled from the disadvantaged villages of County Szabolcs-Szatmár Bereg to Budapest, or other western Hungarian cities. In addition to other documentaries, such as Faluszéli házak (Houses on the Edge of Town) and Mit csinálnak a cigánygyerekek? (What Are the Gypsy Children Doing?), Schiffer made a fictional documentary film, Cséplő Gyuri (1978). This film is about the life of its main character, Gyuri, who attempts to leave the traditional Romani settlement and look for a job in Budapest.

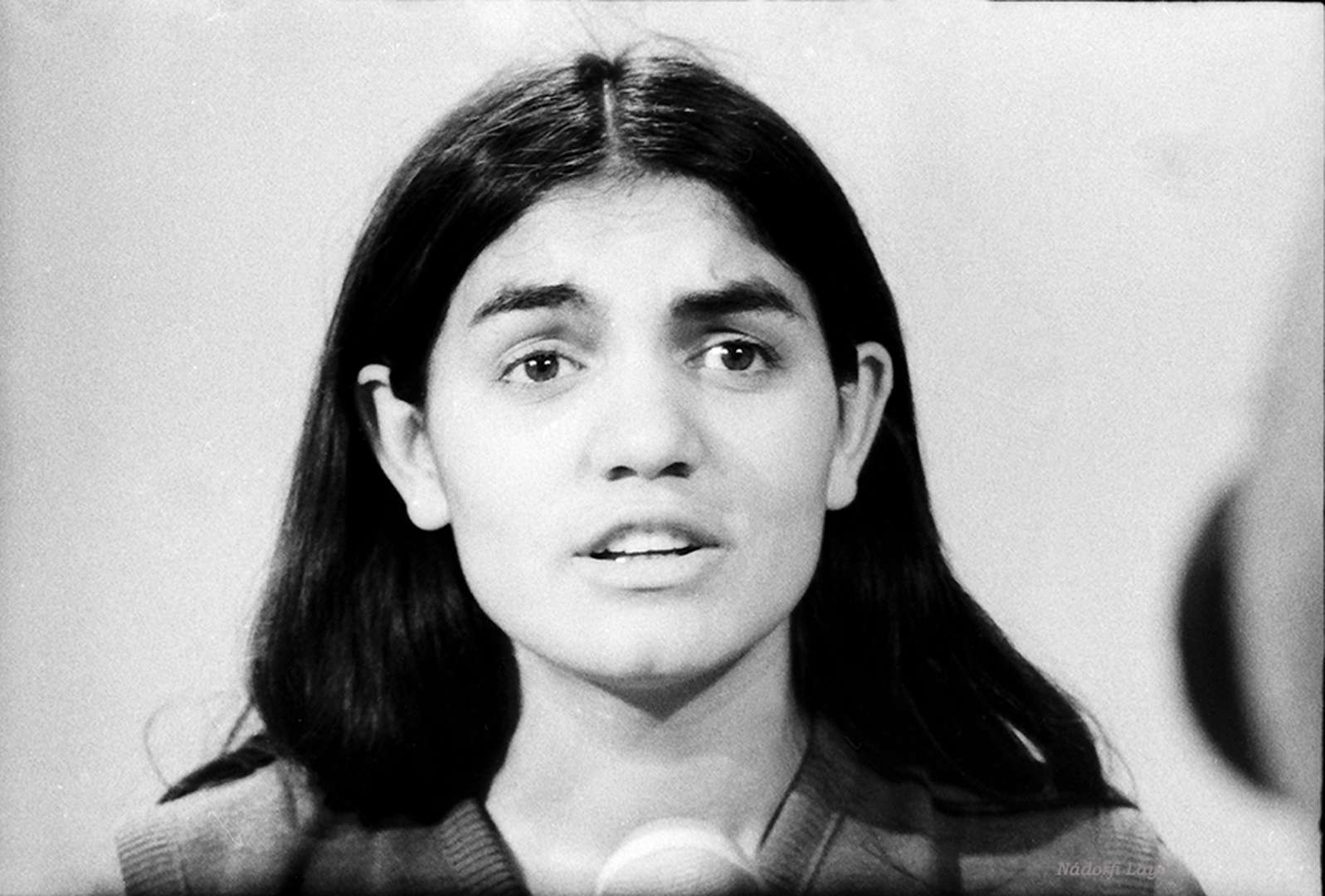

Andrea Pócsik in her eloquent analysis (2013), argues that this film goes beyond the dominant representation of poverty, giving an authority to the Roma protagonist to observe and analyse poverty through his experience. That is to say, this was the first film in the 1970s that gave a specific voice and representation to Romani intellectuals. During the Kadár socialist era, the Central Bureau of the Socialist Party released a statement in 1974, promising to educate Roma alongside non-Roma, as well as to find ways of supporting Roma cultural communities, such as folk-bands and clubs. This cultural initiative, including the “Gypsy Clubs” provided a space for the emerging Romani movement. In Cséplő Gyuri, one of the most significant scenes is when the protagonist meets young Romani intellectuals, Ágnes Daróczi, János Bársony, József Choli Daróczi, József Lojkó Lakatos and Tamás Péli. Despite their different social statuses in the “Gypsy Club”, these individuals still had an opportunity to preserve, re-create and re-articulate Romani culture, which was not promoted and recognized by the Hungarian Socialist Worker’s Party.

Ágnes Daróczi and János Bársony, struggled as a revolutionary couple in the 1970s and 1980s, not just against the Politburo of Central Committee of the Hungarian Socialist Workers Party, but also against the influence of academic racism, such as that represented by the linguists, József Vekerdi and Elemér Várnagy. Vekerdi had deeply influenced ethnographic research on Roma and according to Szuhay Péter, he had even stated that the development of Roma culture had been impeded by lack of tradition. Elemér Várnagy’s, research on Roma strengthened racist misconceptions that Roma inherited predispositions towards stealing and begging. János Bársony succinctly explained, in an interview (2017), that Elemér Várnagy’s work was vigorously challenged by Ágnes Daróczi and himself, with support of international scholars, at a conference organized by the University of Pécs in 1979.