Since the 1970’s, the civil and human rights engagement of Roma in the Federal Republic of Germany has increasingly taken place against a background of generational change and the transformation of the political culture. The election of the social-liberal coalition, under Federal Chancellor Willy Brandt in 1969, brought about a fundamental shift in the political landscape. From the end of the 1960’s onwards, numerous new social movements emerged that have decisively influenced the democratization process of the Federal Republic and challenged the country’s reluctance to come to terms with the legacy of its National Socialist past.

Sinti and Roma in the Federal Republic of Germany

At the beginning of the 1980’s, the German Sinti and Roma civil rights’ movements were fighting for recognition, for the payment of compensation, for dignified forms of remembrance of the Nazi genocide against these minorities, and for the elimination of continuing discrimination. The movements achieved their public breakthrough with a series of spectacular protests that radically queried how the past was being approached, and whether the agencies responsible were, in fact, adhering to the country’s very own constitutionally-enshrined norms. It was not until 1982, that the Federal government officially recognized National Socialist crimes committed against Roma in Europe, as a genocide. Since then, the national umbrella organization, the Zentralrat Deutscher Sinti und Roma (the Central Council of German Sinti and Roma), has been the most important politically representative body for German Roma and Sinti, on both the national and international levels.

The political upheavals in Central, Eastern and South-eastern Europe saw the human rights situation of Roma in these states seriously worsened, and since 1989, many have fled to Germany to escape discrimination and persecution; however, the majority of these refugees have been deported. In response, a movement was founded in 1989 that campaigned for a permanent right of residency for foreign Roma. Whilst German Roma and Sinti were recognized as a national minority in 1995, after many years of campaigning, those Roma who had fled to the Federal Republic continued to fight for the right to asylum. Since the 1990’s, there have been further phases of immigration, and increasing numbers of Roma arriving as refugees, leading to a pluralization of the Roma and Sinti minorities in Germany. The victories achieved by the earlier civil and human rights activists are still influencing the political organizations of the Roma and Sinti living in Germany today, even if, at times, these represent Roma from different nationalities, they are unified in their efforts to eliminate antiziganism (antigypsyism) in Germany and Europe.

In the shadow of Auschwitz – the historical background

Roma and Sinti look back on a six-hundred-year history of existence in Germany. This history has been characterized by continuing prejudice, exclusion, and persecution, by the majority society. Even where there has been interaction between the majority society and the local Roma and Sinti, they were increasingly being viewed as criminal elements. Since the nineteenth century, both groups have been subjected to restrictive legislation and strict police surveillance. Following the National Socialists assumption of power in 1933, Roma and Sinti were gradually ostracized, excluded, expatriated, dispossessed, deported, and eventually exterminated.

Only a few thousand Roma and Sinti survived the National Socialist persecution, forced labor, forced sterilization, and imprisonment in concentration and extermination camps. Following the end of the war in May 1945, they returned to their hometowns, severely traumatized. Whereas the Federal Republic of Germany, following its founding in 1949, acknowledged the Shoah (Holocaust) and awarded the Jewish victims compensation, the Nazi (Porrajmos) genocide of Roma and Sinti was erased from the perception of the public for decades. Police detectives who had formerly been directly involved in the Nazi persecution of Roma and Sinti were able to continue their careers, without ever having to face legal prosecution. Officials compromised by Nazi affiliations, disputed and denied the racial persecution of Roma, even defending their actions as “crime-prevention measures”. This view was reflected in a prominent judgement by the Federal Court of Justice in 1956, preventing scores of Roma and Sinti who had been persecuted, from receiving compensation for many years. The courts chose to believe the one-time perpetrators over the victims.

Furthermore, police authorities and so-called “race researchers”, kept key files locked away, which would have furnished indispensable evidence of this persecution. In Bavaria, the so-called Landfahrerordnung (vagrancy ordinance), remained in force until 1970, curtailing the basic rights of Roma. At the Bavarian Vagrancy Office (attached to the State Office of Criminal Investigations), police detectives maintained a registry of Roma and Sinti from across the whole of West Germany. These included fingerprint records, detailed personal information, and even tattooed concentration camp numbers. These files had, in part, already been collated during the Nazi period, and were subsequently used in many compensation cases to dismiss claims by Roma and Sinti who had survived the Porrajmos (Romani genocide). Using these files, Roma and Sinti were frequently subjected to ongoing discrimination, in a democratic state that allegedly guaranteed constitutional rights.

The beginnings of civil rights activism

The generation of Porrajmos survivors were severely affected by the experience of Nazi persecution and the deaths of family and numerous relatives. Picking up the threads of their lives before Nazi persecution was scarcely possible, in a country where the perpetrators remained unpunished. Roma and Sinti communities, which had always felt themselves to be German, were seriously shaken. Roma and Sinti were forced to continue living on the fringes of society following the war, meaning only a few dared to protest against their discrimination. As early as the end of the 1940’s, Oskar and Vinzenz Rose. brothers from southwest Germany, joined forces with other Porrajmos survivors and sought to have the Nazi crimes committed against Roma and Sinti investigated, through proper legal channels. Prosecutions proceeded against the former ‘desk murderers’ but were soon dropped. The first Interessengemeinschaft rassisch Verfolgter nicht jüdisch Glaubens, founded by the Rose brothers, was unable to gain public attention.

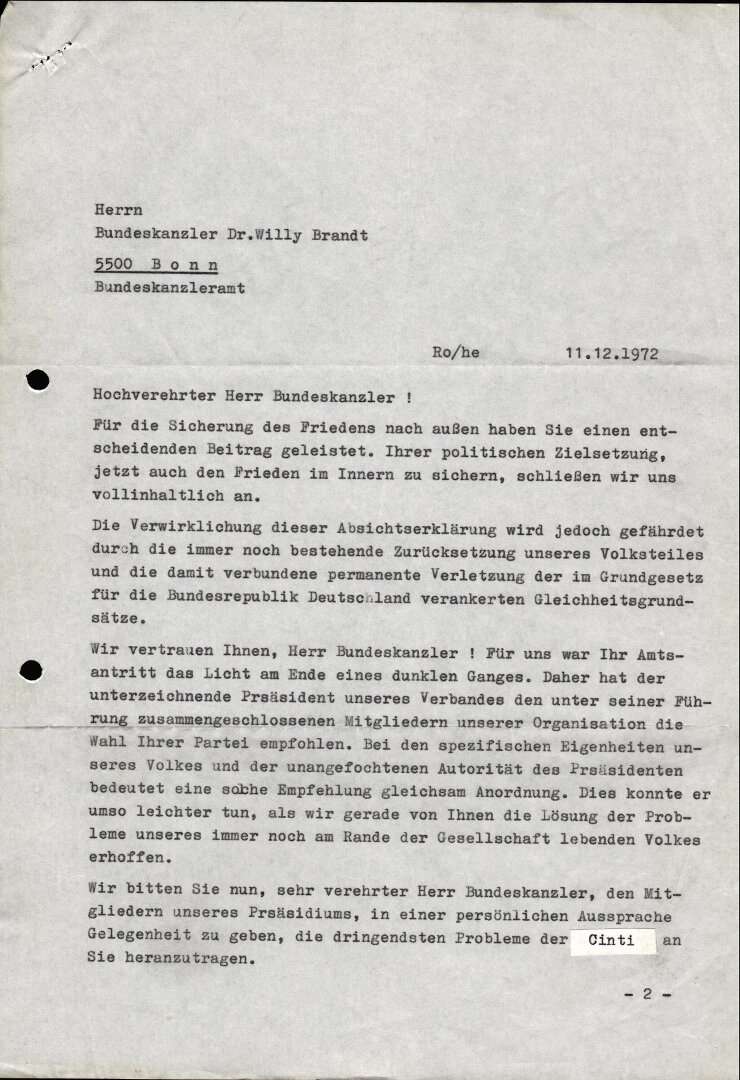

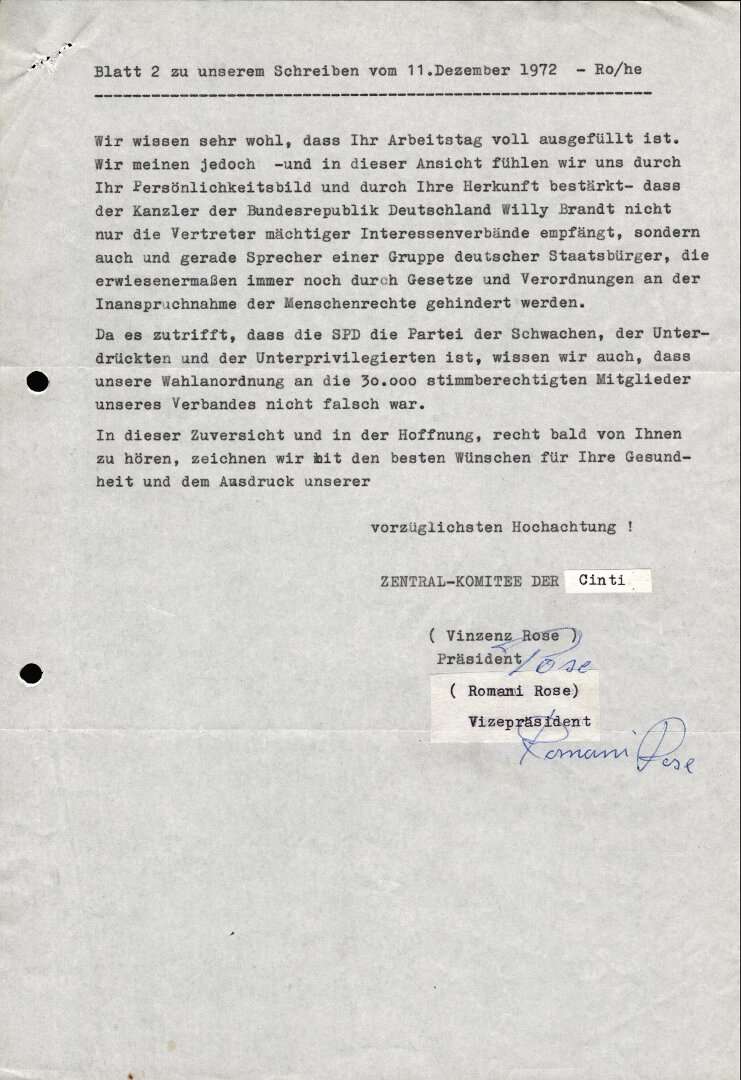

In the 1970’s, a decade strongly influenced by political and cultural change, Roma civil rights initiatives gained a fresh impetus. The international Roma movement also influenced the activism of German Roma and Sinti, with the younger generation now becoming active. Together with his nephew, Romani Rose, Vinzenz Rose founded the Zentral-Komitee der Cinti and the Verband Deutscher Sinti. Both pinned their hopes on the politics of reform and peace, pursued by the social-liberal Federal government under Chancellor Willy Brandt, and petitioned him personally to support their civic engagement.

They published pamphlets to win over members of the Roma and Sinti communities, and convinced them to support their political objectives. Their goal was to establish a trans-regional advocacy group to gain political recognition, receive compensation, and eliminate discrimination. After the Sinto, Anton Lehmann was shot dead by the police in Heidelberg in 1973, the Verband Deutscher Sinti organized the first public demonstration against the discrimination of Roma and Sinti. While still hesitant, these first steps politicized a large number of the communities’ members.

The public breakthrough of the Roma civil rights movement

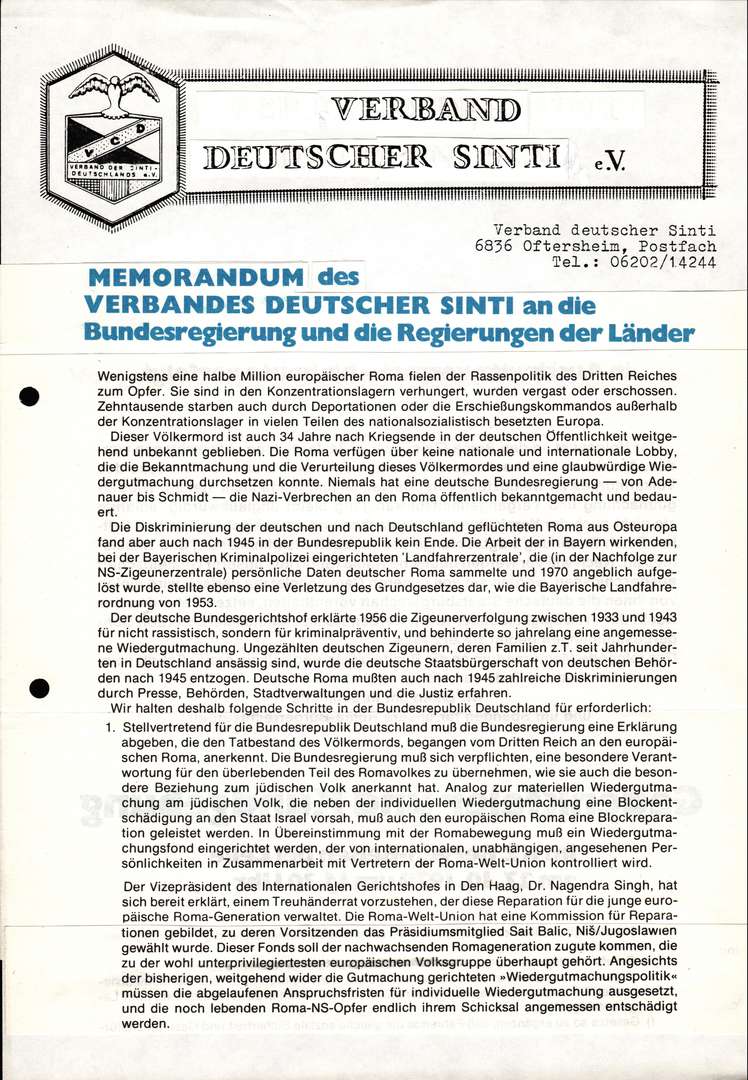

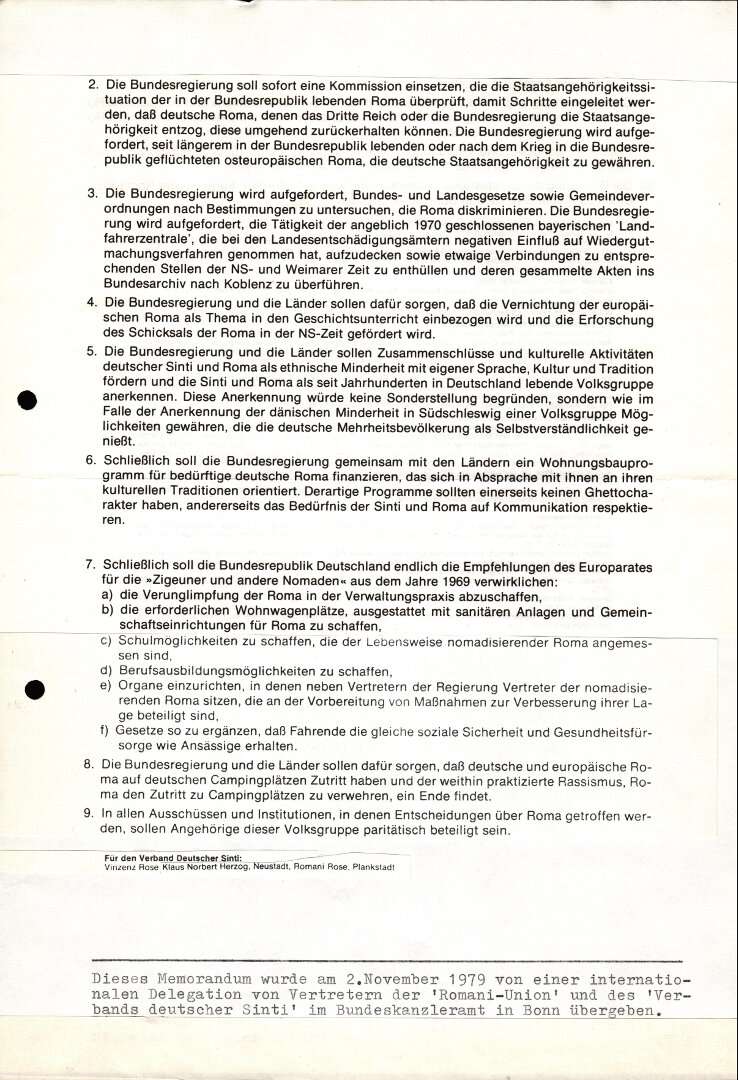

Supported by the human rights organization, Gesellschaft für bedrohte Völker, the Verband Deutscher Sinti launched a systematic public campaign in 1979, to gain official political recognition of the Nazi genocide committed against Europe’s Roma. Roma and Sinti increasingly demonstrated against the curtailing of their rights – guaranteed by West Germany’s Basic Law (or fundamental law) – of equality and freedom of movement. The first international commemorative rally, held on 27th October 1979 at the site of the Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp Memorial, remembered those Roma and Sinti murdered by the Nazis. Amongst the 2,000 participants were 500 Roma from twelve European states, national and international politicians, and representatives of other groups of victims of the Nazis.

The main speaker at the rally was the first president of the European Parliament, Simone Veil. She was herself Jewish, and had survived Auschwitz extermination camp, finally being liberated while at Bergen-Belsen, where her mother had earlier died of typhus. The national and international press reported on the event, recalling the Nazi genocide, and the ongoing antiziganism (antigypsy prejudice) in the modern Federal Republic of Germany. A few days later, a delegation of representatives of the Verband deutscher Sinti, the Gesellschaft für bedrohte Völker, and the International Romani Union handed over a memorandum to the Federal Chancellery, stating the most important political goals of the Roma and Sinti civil rights movement.

The road to recognition

On Good Friday 1980, a few months after the rally in Bergen-Belsen, twelve Sinti and Roma went on a hunger strike at the site of the Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial. The strike became a key event for the Sinti and Roma civil rights’ movements in Germany. It received a particularly strong moral boost from the participation of Porrajmos survivors, some of whom wore their one-time prison uniforms.

During the week-long strike, the participants demanded information on the whereabouts of the files once kept by the former Vagrancy Office, and the end of the targeted registration of Roma and Sinti by the police. The speaker on behalf of the strikers, Romani Rose, negotiated with the Bavarian Interior Ministry, whilst the protests triggered broad public sympathy and marked a turning point in the public’s perceptions of the communities. Around 100 journalists from Germany and abroad, reported daily on events unfolding in Dachau. Eventually, the Bavarian government publicly conceded; discrimination against Roma and Sinti had to cease and attitudes needed to change. To officially conclude the strike, the activists welcomed the Federal Minister of Justice, Hans-Jochen Vogel, to Dachau on 12th April 1980. He promised his support and described the protest as lending “very important impetus” to the fight to eliminate prejudices.

However, the whereabouts of the files held by police, remained uncertain. The Roma and Sinti civil rights’ movements had set themselves the goal of locating these Nazi ‘race records’, and the transfer of them to the Federal Archive in Koblenz, where they were to be made publicly available for researchers of the genocide. Inquiries revealed that ‘race researchers’ had, in fact, been regularly studying the secretly-held files for their own pseudo-scientific purposes. In September 1981, eighteen Sinti occupied the basement of the Tübingen University archive and demanded these documents. After just a few hours, a number of files were transferred to the Federal Archive. However, they did not contain the 20,000 so-called Nazi, ‘race assessment reports’ compiled by the Office for Racial Hygiene Research, the documentary basis for carrying out the Nazi genocide of the Roma and Sinti. These documents remain missing.

In February 1982, nine associations active in the civil rights movement merged under an umbrella organization, the Zentralrat Deutscher Sinti and Roma, and elected Romani Rose as chairperson. This enabled activists to establish a representation for German Roma and Sinti that was accepted as a partner in political dialogue, by the Federal government. Only a few weeks later, Chancellor Helmut Schmidt officially recognized the Nazi genocide of Roma and Sinti, for the first time. Schmidt declared:

He also spoke of the need for making amends and emphasized the duty of the Federal Republic of Germany to compensate victims and improve their position in society. This recognition of past crimes of the state and the present needs of the victims, in accordance with international law, signaled a new beginning in the relationship between the Federal government and German Roma and Sinti.

“Severe injustice was inflicted on the... [German Sinti and] Roma by the Nazi dictatorship. They were persecuted for racist reasons... These crimes constitute a genocide [against them]”

Helmut Schmidt

The founding of the Zentralrat improved the networking of the Roma and Sinti minorities’ regional and local associations, and increased dialogue with politicians and authorities alike. In September 1982, the Zentralrat was able to begin its work, with headquarters in Heidelberg and funded by the Federal government. Since then, subsequent chancellors and Federal presidents have reiterated the recognition of genocide. Thanks to effective campaigns that have drawn considerable public attention, the Zentralrat has been able to initiate a fundamental change to the process of awarding compensation for discrimination to Roma and Sinti. Moreover, the civil rights movement has been able to establish a commemoration of the Nazi genocide against the communities that was both moving and vibrant. In 1997, the first permanent exhibition on the genocide was opened, the Documentations – und Kulturzentrum Deutscher Sinti und Roma, in Heidelberg. Since 2012, a national memorial, in the unified German capital of Berlin, commemorates the victims murdered during the Nazi dictatorship.

Protests against special registration by the police

As a result of the discussion in the Federal Republic, about the genocide against Roma and Sinti being neglected, those involved went unpunished, in particular those serving in the Republic’s police force. Racism towards Sinti and Roma remained decades after the war. The special registration of the communities, already imposed during the German Empire, was continued after 1945. Registration was undertaken by Vagrancy Offices attached to the newly established state offices for criminal investigations. At the end of the 1960’s, the Federal Criminal Police Office issued guidelines for detectives and police officers, in which the author, using Nazi jargon, justified continuing special registration of Sinti and Roma. Police journals, all-points bulletins, and press releases bore the imprint of antiziganist (antigypsy) prejudices. This moved Roma and Sinti activists to demonstrate in front of the Federal Criminal Police in Wiesbaden, in January 1983, on the fiftieth anniversary of the Nazi’s assumption of power. Concentration camp survivors were amongst the 250 demonstrators who gathered from across West Germany. Although the government, with the Federal Criminal Police, promised to cease special, ethnic-based registration, cases of this form of discrimination continue to come to light, down to the present day.

Civil and human rights activism for Roma in the post-1989 period

Whereas the civil rights movement of German Sinti and Roma have initiated slow changes and gained hard-fought successes since the 1980’s, the transformation processes triggered by the political upheavals in Central, Eastern and Southeastern Europe, have had dramatic consequences for many Roma. Violence and antiziganism (antigypsyism) have reached dangerous levels in many of the former Communist states. Nevertheless, only a few Roma who have fled this perilous situation, have been granted asylum in the Federal Republic of Germany, so that most live under the constant threat of deportation. Despite the heated debate about refugees and migrants in the European Union, human rights violations committed against Roma in these countries, have scarcely been mentioned or publicly discussed.

Following the reunification of Germany in 1990, xenophobia and violent racism against Sinti and Roma has increased. Since 1989, Rudko Kawczynski has coordinated with the Roma und Cinti Union, to organize a number of powerful protests, such as a hunger-strike, a protest camp on the site of the Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial, the occupation of certain churches, and the so-called ‘pauper marches’, all of which have sought to put a stop to official deportations of migrant Roma. Other regional and local initiatives have strengthened the movement, whilst these demonstrations were, in part, greeted by national and international statements of solidarity. In some cases, residence permits were issued; however, a general solution guaranteeing the right of permanent residence for Roma refugees in the Federal Republic, has not been achieved. After the outbreak of the Kosovo War, where Roma, Ashkali and Egyptians became caught up in the midst of the conflict between Serbs and Kosovan Albanians (Kosovars), the Zentralrat Deutscher Sinti und Roma appealed to the German government, and the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), to become more actively involved in protecting and guaranteeing the minority rights of Roma in their respective countries.

In the wake of the ethnic conflicts in some of these former Communist states, the Council of Europe has also increased its efforts to establish legally-binding instruments securing minorities’ protections. However, concrete implementation lies with these European nation states. With the signing of the Council of Europe’s Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities on 11th May 1995, the Federal government accorded German Sinti and Roma the same status as other minorities in Germany. On this legal basis, German Roma and Sinti associations have ensured that standards of minority protection are adhered to and have gained cultural funding in some federal states. In 2012 the Bundes Roma Verband was founded, an umbrella organization for associations of Eastern European Roma, in Germany.

Despite the achievements of the first Roma and Sinti civil and human rights movements, many authorities and much of the populace in Germany continue to view them with animosity, prejudice and discrimination. A diverse array of organizations, associations, youth groups, and initiatives continue to campaign vehemently for the civil and human rights of Sinti and Roma, and actively seek to eliminate the antiziganism (antigypsyism) that still prevails in Germany.

Rights held by: Daniela Gress | Licensed by: Adrian Marsh | Licensed under: CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International | Provided by: RomArchive