Summary / Short description

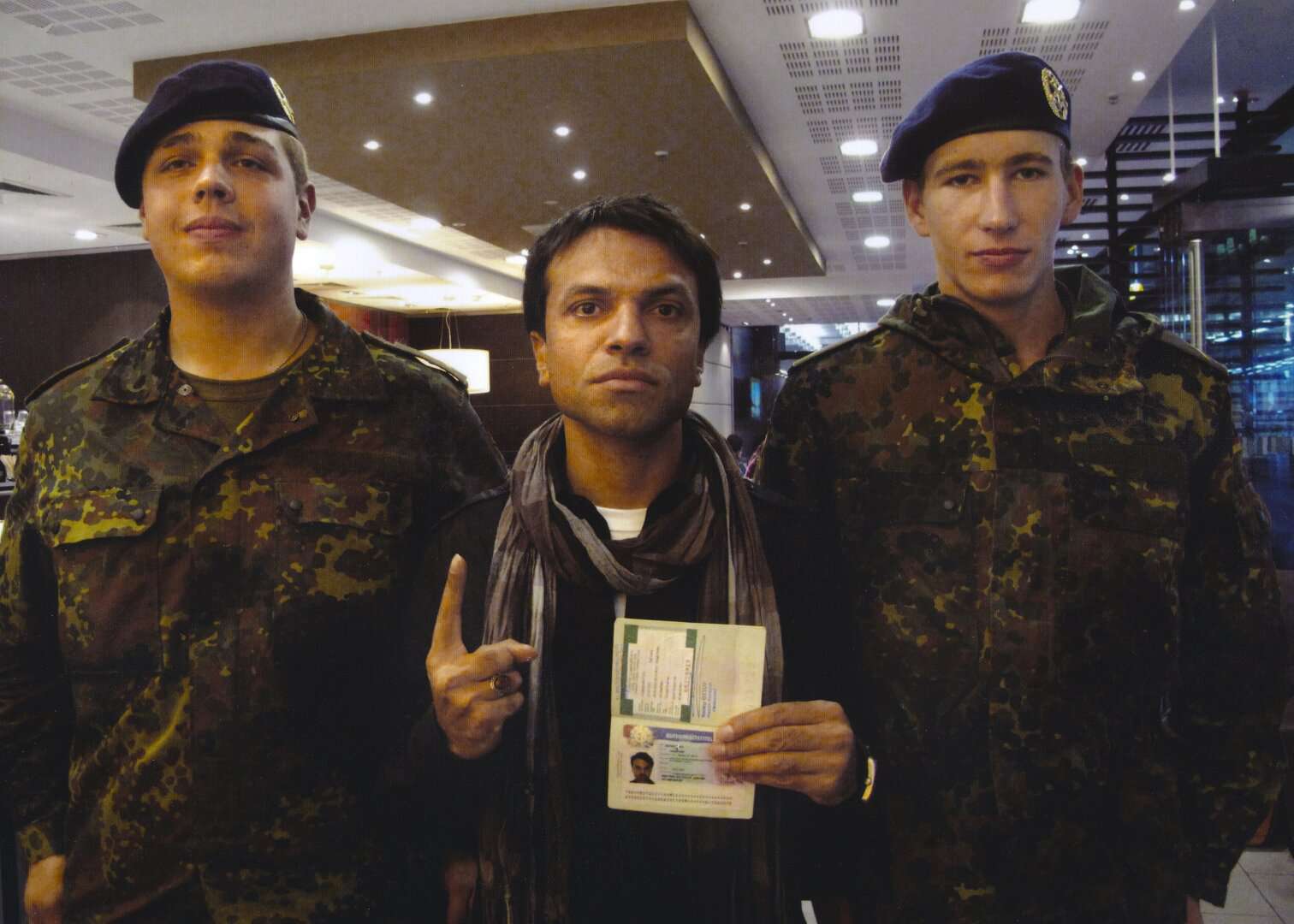

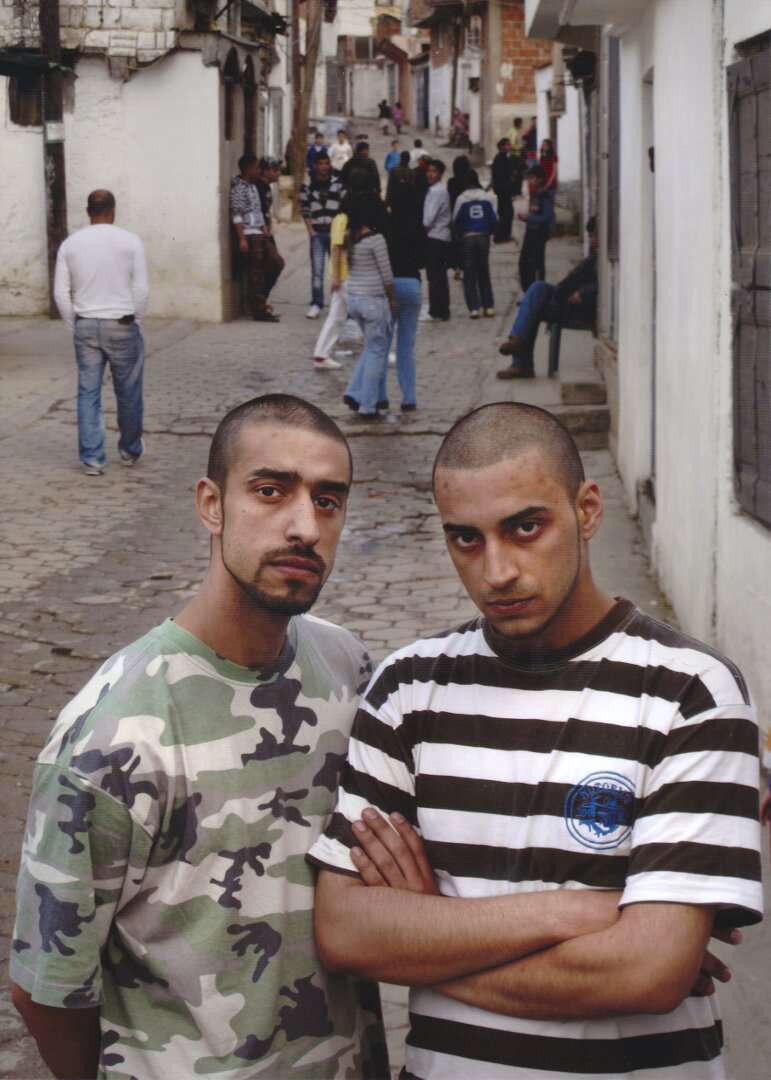

The concept of the project Rewriting the Protocols: Naming, Renaming and Profiling is based on the urgent need for a critique of and change to the long history of racial profiling and stereotyping of Romani people through various legal and cultural protocols, rules and documents. Such political and social phenomena are unfortunately still present and these issues continue to generate new protocols which are in return used to label and discriminate against many different Romani individuals and communities based on stereotypical racialised representations, derogative denominations and forced similarities.

The selected artists (Sead Kazanxhiu, Nihad Nino Pušija, RJKaS, Selma Selman and Alfred Ullrich) are challenging this vicious circle, addressing such issues and social phenomena with rigour and precision in their artistic practice by using various art media and forms of expression and action (photography, video, live art, digital art, public performance or activist interventions). Through their art projects, the artists are fighting the established social ‘order’ and calling for changes to the perception, self-perception, and representation of Romani people by proposing certain counter-strategies, such as rewriting art history and revising identitarian politics through renaming, over-identification, irony, as well as other artistic approaches from the position of contemporary art practitioners.