Selma Selman | You Have No Idea | photograph | Serbia | 2016 | vis_00229_10 Rights held by: Selma Selman | Licensed by: Selma Selman | Licensed under: CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International | Provided by: Selma Selman – Private Archive

The concept of the project Rewriting the Protocols: Naming, Renaming, and Profiling is based on the urgent need for a critique and change of the long history of racial profiling and stereotyping of Romani people through various legal and cultural protocols, rules and documents. Such political and social phenomena are unfortunately still present and these issues continue to proliferate new protocols which are in return used to label and discriminate different Romani individuals and communities based on stereotypical racialised representations, derogative denominations and forced similarities.

The selected artists Mo Diener, Sead Kazanxhiu, Nihad Nino Pušija, RJSaK, Selma Selman and Alfred Ullrich are challenging this vicious circle. With their art projects and from the position of contemporary art practitioners, they are fighting the established social ‘order’ and calling for amendments to the perception, self-perception, and representation of Romani people by proposing certain counter strategies such as rewriting art history and revising identitarian politics through renaming, over-identification, irony and other artistic approaches.

The project therefore aims to unravel the hidden patterns of colonisation and subjugation, but also to stress the countermovement against these patterns and pursuit of new Roma subjectivities which resist and promote agonistic agency, solidarity based on difference and the urgency for decolonisation, rather than passively accepting the current condition.

There is still a great population of individuals (citizens and non-citizens alike) who are made invisible and are silenced by isolation and the violation of their basic human rights. Even if someone may not be capable of transcending racism and thus cannot justify the concept of a post-racial society or may not be capable of unravelling all the inherited contours and inflexions of representation, that person should take on board the responsibility of speaking up against injustice and discrimination.

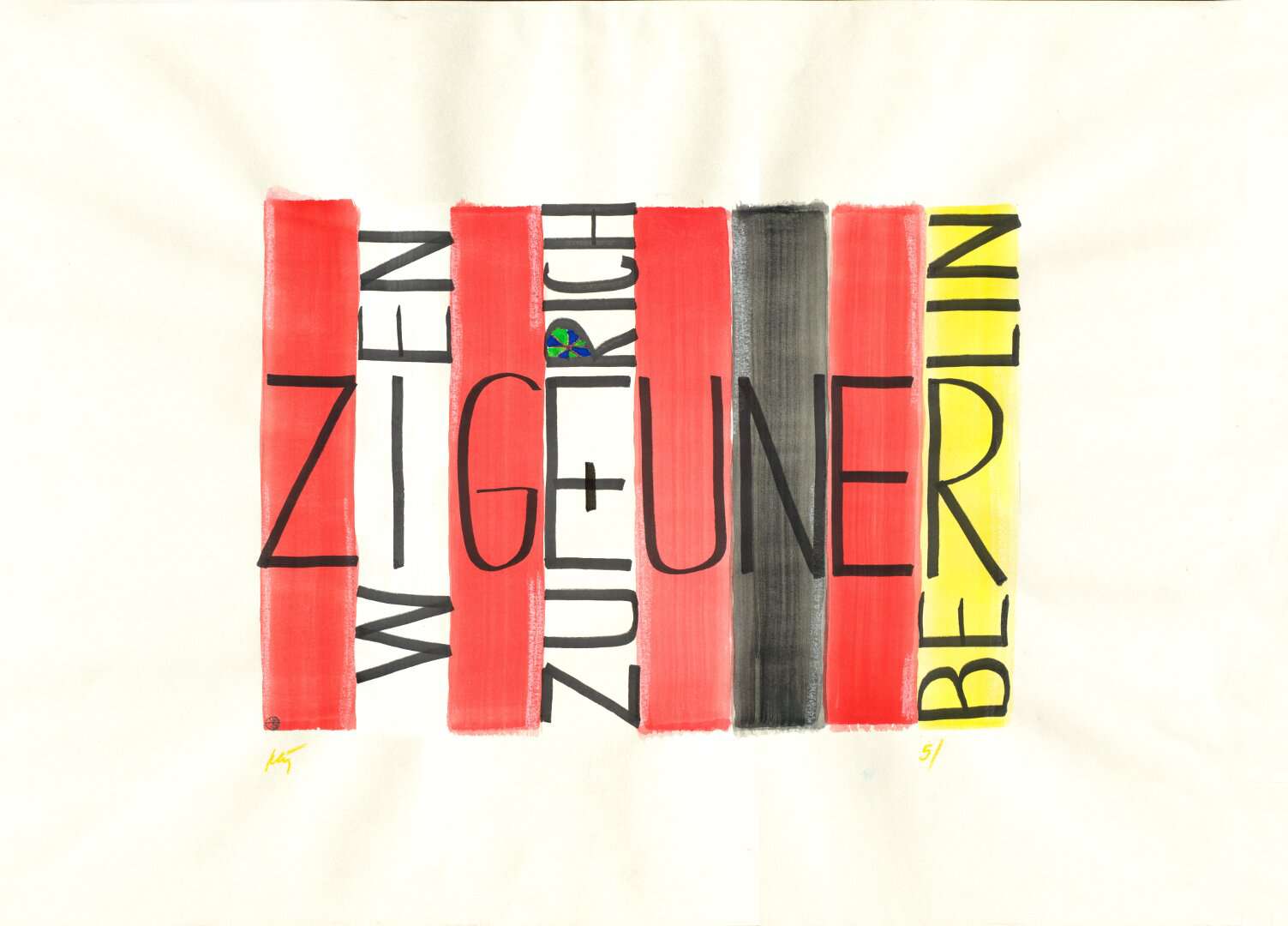

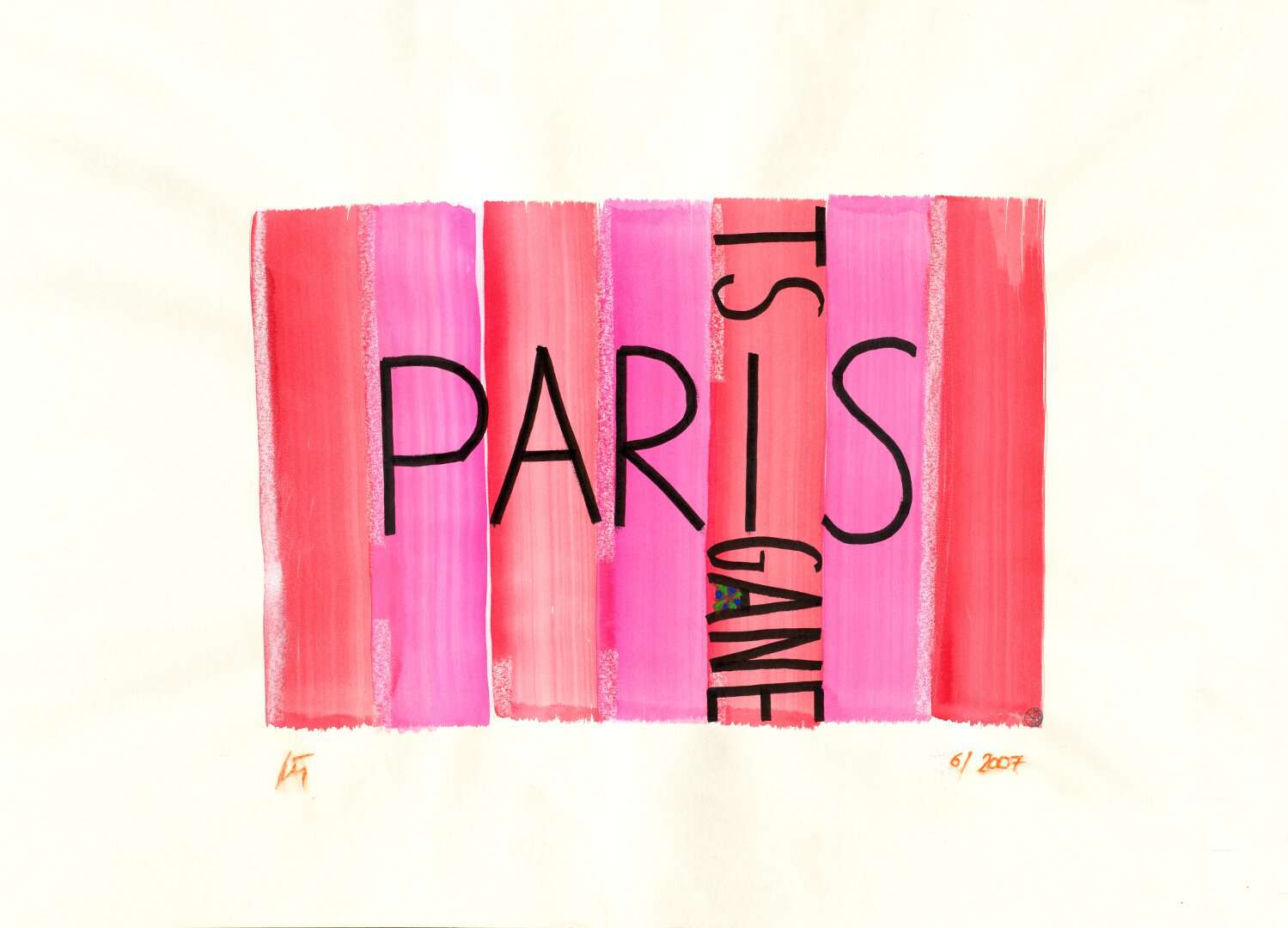

The arbitrariness behind the term Roma was one of the first widely-agreed political decisions and actions in the history of Roma activism. Although the usage of the word ‘Roma’ was agreed by the majority of the attendees and observers at the 1971 international meeting of Romany people in Orpington, UK, as a conscious political decision to denote various groups, communities and cultural phenomena of Romani origin, and has been applied in this manner since then, the term ‘Gypsy’ is still widely in use as a derogative exclamation and racial slur.

Many restaurants still serve food under the label ‘Gypsy’ to stress the spicy and hot flavour of certain dishes, Western musicians use it as a term to emphasise the supposedly exotic provenience of the rhythm and pace of their music, while fashion designers employ it whenever adding more frills and patches to their collections. The images of caravans, wheels and other symbols dominate with many programmes related to Roma culture as symbols for the assumed stereotypical ‘Gypsy’ lifestyle characterised by wanderlust.

Although the usage of the term ‘Gypsy’ is clearly not always motivated by and intended as racism, the perpetuation of the use of the term and the proliferation and distribution of stereotypical images certainly give way to and justify the subconscious and conscious patterns of racist behaviour.

What is it like to be... Roma?

‘What is it like to be Romani’ resonates with the question posed by Thomas Nagel, and it could be asked here too. (In: Mortal Questions, New York: Cambridge University Press, 1979, pp. 165–180).

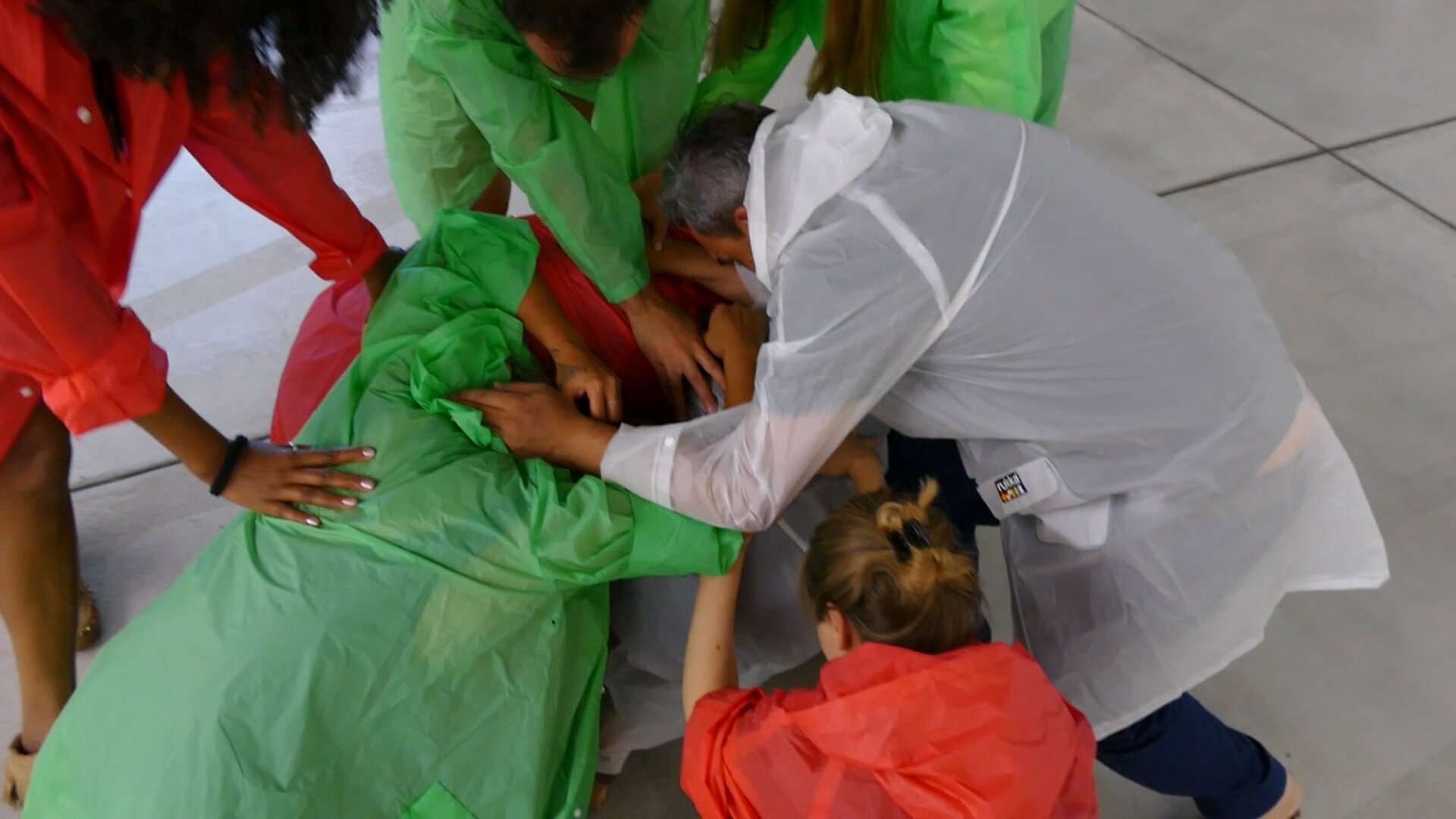

The work You Have No Idea is Selma Selman’s answer. She ponders the urgency of trying to understand the complex historic, socio-political, and cultural background which determines the Roma as the more general and common denominator for different traditions and communities (e.g. Sinti, Kale, Manush, Gitans, Gitanos, and other Roma).

The artists exhausts herself and her voice by shouting the statement You Have No Idea as loudly as she can throughout the whole performance.

Thomas Nagel originally asked the philosophical question ‘What is it like to be a bat?’ in his renowned eponymous text, and this question is still a powerful and viable metaphor for the impossibility of any attempt to understand others. (These arguments were first presented in Milevska, Suzana: ‘The Difference between Saying and Doing in the Use of “We”’ in Gallery8 Team (ed.): Gallery8 Contemporary Art Space 2013–2015, Budapest: Gallery8 & European Roma Cultural Foundation, 2016, pp. 18–30, and in the lecture ‘Contingency and Clusivity of the “We”’, RJSaK, Shedhalle, Zurich, 2016)

But in my text and project I propose to paraphrase the question and ask: is it really so difficult to understand another human being, and why this would be an issue at all?

Are Roma really so different? Isn’t this question an invitation to yet another essentialisation? And if it is true, what made this communication and mutual understanding so difficult in historic and cultural terms?

Every human mind is culturally redesigned so that only our ability and desire to be engaged in ‘presenting ourselves to others, and ourselves’ (Dennett, D. C.: ‘The Origins of Selves’, Cogito, no. 3, 1989, p. 169) and representing ourselves ‘in language and gesture, external and internal’ (ibid) make us different from others. Nagel warns us that all relevant physical facts are not enough to provide us with proficient answers to the question ‘what is it like to be’ different, but this does not mean that we should not listen, empathise, and co-exist. (Nagel: 1979, p. 165)

In the light of recent disputes about cultural appropriation it becomes extremely sensitive and questionable to use ‘we’, exactly because of the gap between uttering the pronoun and acting out in accordance with its promise, particularly when hijacking the ‘we’ from the privileged position of the gadji (non-Roma) and forgetting about Thomas Nagel’s warning about the cognitive impossibility of fully understanding what it is like to be someone else (even when discounting cultural similarities or differences). (Nagel: 1979, pp. 165–180).

However, proximity and empathy may still be the necessary aporic relations to strive for in order to work through ‘we’ even when conscious of the approximate impossibility.

The artists, activists and theorists contributing to the project address the urgency of openly challenging the misunderstandings, stereotypes and controversies surrounding the names used for addressing Roma people, as well as the relevance of the meaning of the term ‘Roma’ and the reasons for the reluctance towards its use among both non-Roma and some of the Roma communities.

The project is invested in the right to determine and decide the position towards the name Roma, through which Roma could utter their statements of belonging or non-Roma could act as agents of empowering and solidarity with Roma. This is challenged by pushing for some concrete critique of derogative and pejorative terms such as ‘Gypsy’, ‘Cigani’, ‘Zingar’, ‘Tsigane’ or ‘Zigeuner’ that mostly function as stigma rather than as proper ethnic names, often overburdened with anti-Roma sentiments.

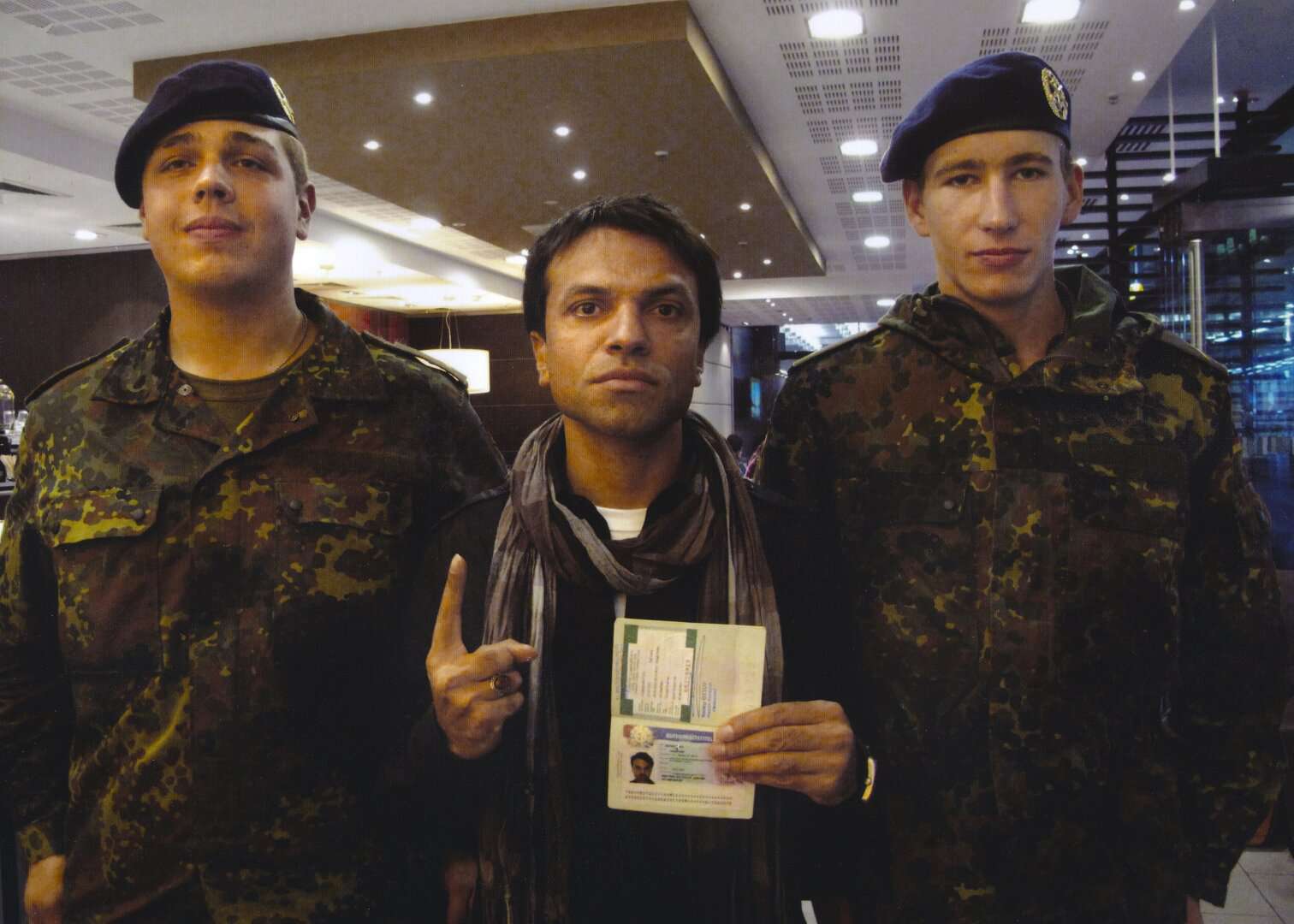

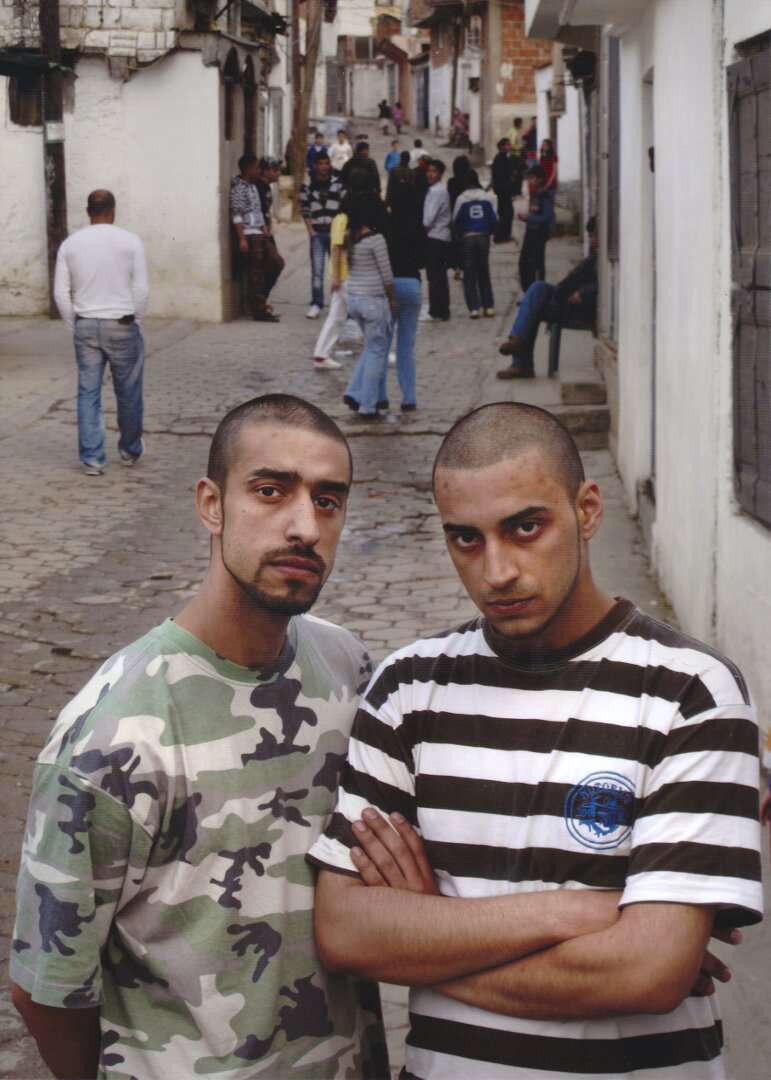

Nihad Nino Pušija’s project titled Duldung Deluxe [Toleration Deluxe] reflects on the document claiming ‘toleration’ in its name but is actually directly related to the deportation of Roma teenagers and young adults from Germany to their countries of origin such as Bosnia, Serbia or Kosovo. (This refers to the partial permit which was introduced in 2009 when the German government signed a repatriation agreement to deport up to 14,000 refugees to the successor states of the former Yugoslavia. According to Lith Bahlmann’s 2012 text about the Duldung Deluxe project, this number included around 10,000 Roma.)

While there is no legal proof of discrimination, half of the deported Roma since 2009 have been children who were mostly born in Germany. Therefore, the legal term ‘repatriation’ does not reflect the fact that Germany was their home country. Roma children have been deprived of their homes and forced to adopt their predecessors’ nomadic lives without having decided or wanting to do so, thus perpetuating the long-held myth and common stereotypical image.

The reference to the absence of Roma names and images of Roma personalities in public places, to defamatory images of Roma and the use of derogative names and inscriptions, corresponds to the visual culture arguments about the profound impact of proliferating and widely distributing images with problematic content in public spaces, but is also used as a platform for calling for claiming and allocating evident social presence to a larger extent for relevant references to important Roma personalities.

Who has control over naming and renaming, and how can this power can be used to reproduce and distribute certain dominant cultural and moral principles?

In the view of Gilles Deleuze, the first moment of giving/receiving a name is in itself ‘the highest point of depersonalization’ because we acquire ‘the most intense discernibility in the instantaneous apprehension of the multiplicities’ belonging to us. This project puts under pressure the hegemonic regimes of representation which are present and which endure through arbitrarily chosen names as well as by means of internalised strategies of self-representation that are imposed upon individuals through nominal structures.

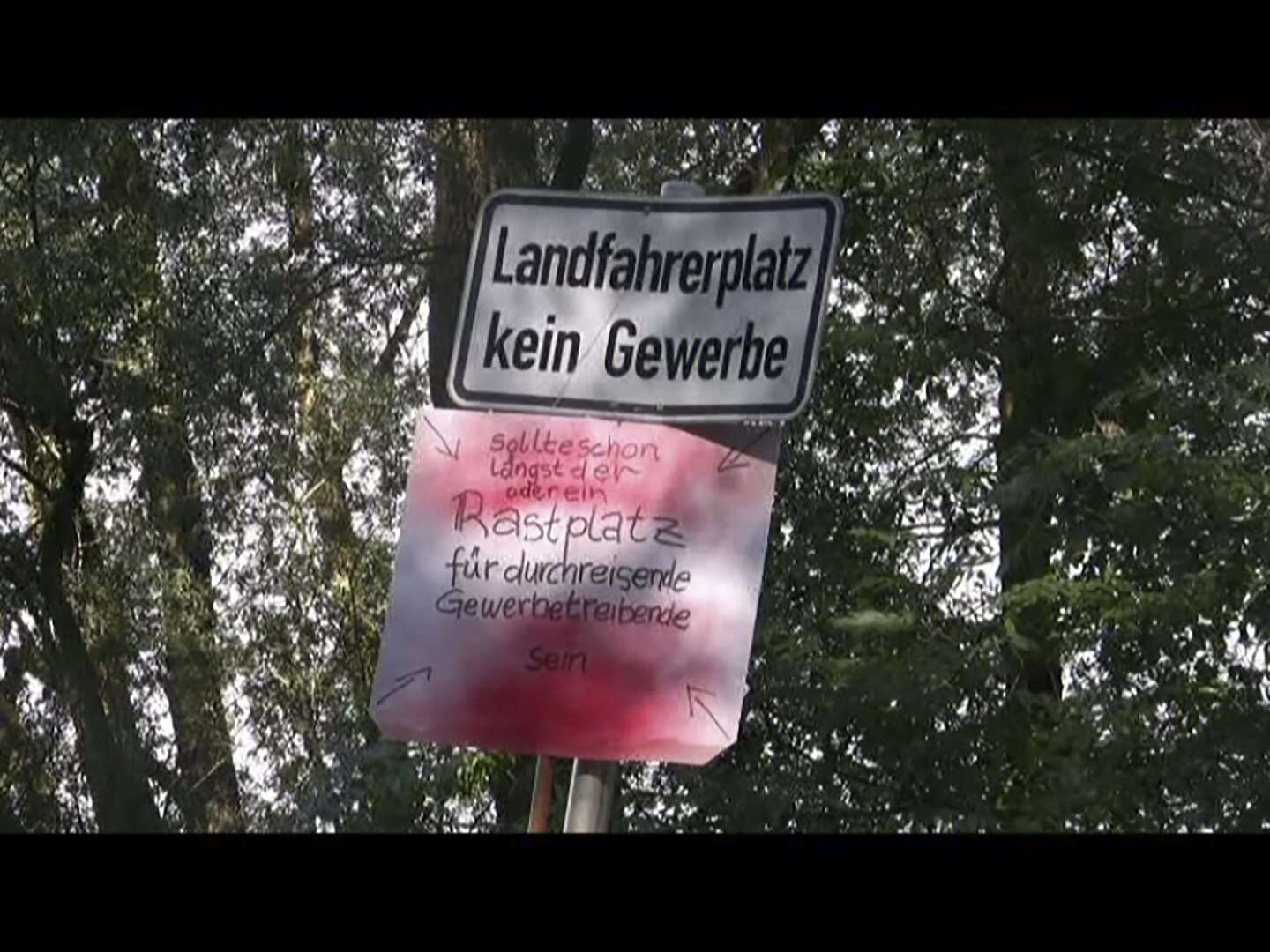

Some aspects of this project were incited by the urgency to address recent cases of individual and collective displacements, evictions and deportations of Roma citizens from their homes in many European countries. For example, Alfred Ullrich’s works were based on the artist’s initiative which led to the correspondence between the chairwoman of the Künstlerverinigung Dachau and the mayor of Grosse Kreisstadt Dachau about the signs ‘Landfahrerplatz kein Gewerbe’ [Site for Travellers: No Trading’].

The artist’s persistent initiatives urging action eventually persuaded the local authorities to remove the derogatory signs from public sight. The result of the process was Ullrich’s work Crazy Water Wheel (2009–2011), which consists of two videos. The first video is a loop showing the turning wheel of a watermill near Dachau Nazi extermination camp, referring to the eternal recurrence of racism.

Alongside the watermill wheel is a documentary showing an informal private performance of the artist commenting on the traffic signs ‘Landfahrerplatz kein Gewerbe’, which warn that itinerants are not allowed to trade or peddle in the area. At the time these signs were still in use in Bavaria. In the work the inscription is crossed out, a simple action that highlights how seemingly neutral regulations in fact enforce the segregation of Roma travellers from others.

The artist is recorded as he questions and crosses out the inscription on the street sign by holding up three signs, one after another: a question mark, a cross and a sign suggesting a replacement term – ‘Rastplatz’ [Stopping Place]. He thus points to the relevance of each term and name perpetuating the same old stereotypes, just like the wheel itself.

Clearly the discrimination on the basis of ethnicity is preserved through language and visual public memory, something that gives way to reinforcing the existing stereotype of Roma people as ‘exotic’ creatures full of wanderlust, who are always ‘on the move’. Although this might be true, Ullrich’s (and Pušija’s) work points to the fact that this has not always been their own chosen way of life.

The role of the contemporary Roma artists in the exhibition is not limited to uttering anti-racist testimonials and highlighting injustice, for the project also adopts the strategy of suggesting new paths and expressions as a kind of agency –the function that used to be played by the term ‘Roma’ – in inflicting social change both within the artists’ own communities and in the wider context of art and political institutions and in the general public sphere.

Speaking out about controversial issues has a price, as Sead Kazanxhiu (an Albanian artist of Roma background) so eloquently suggests. In his video performance A Choice to Be Made, A Price to Be Paid (2015), Kazanxhiu refers to the issue of right to territory and land – a right which is usually denied to Roma in many different contexts.

Not only the title but also the statement that, when you make a choice, ‘there’s something you have to agree to’ were based on a quotation by Romanian sociologist Nicolae Gheorghe, relating to the contradictions stemming from what in Western terms is the ‘vaguely defined’ concept of ownership among Roma with respect to land and property. In his work, Kazanxhiu metaphorically addresses how the complex implications of Gheorghe’s claim about the issue of ‘Romani phuv’ [Romani land] are controversial.

During the first part of the video Kazanxhiu prepares a meal out of mud called shishik in Romani, which in Roma tradition is a special soil used for hygienic rituals (in contrast to the usual understanding of mud as a material for defilement). (Isto, Raino: ‘Choices to be Made: An Interview with Sead Kazanxhiu’, Afterart – blog about art and society, 25 July 2016, https://afterart.org/2016/07/25/choices-to-be-made-an-interview-with-sead-kazanxhiu/).

During the second part he plays the role of an educated Roma person (dressed as a bureaucrat) who stages the process of negotiating, conducting discussions and making decisions in order to fulfil the dream of living longer at a particular spot and hence prevent the constant moving.

In the struggle to right the racial bias, social inequalities and (mis)representations that characterise our world today, the artists’ role is seen as unravelling these mechanisms (often by making them ironic or over-identifying with them) and simultaneously counteracting them with positive actions.

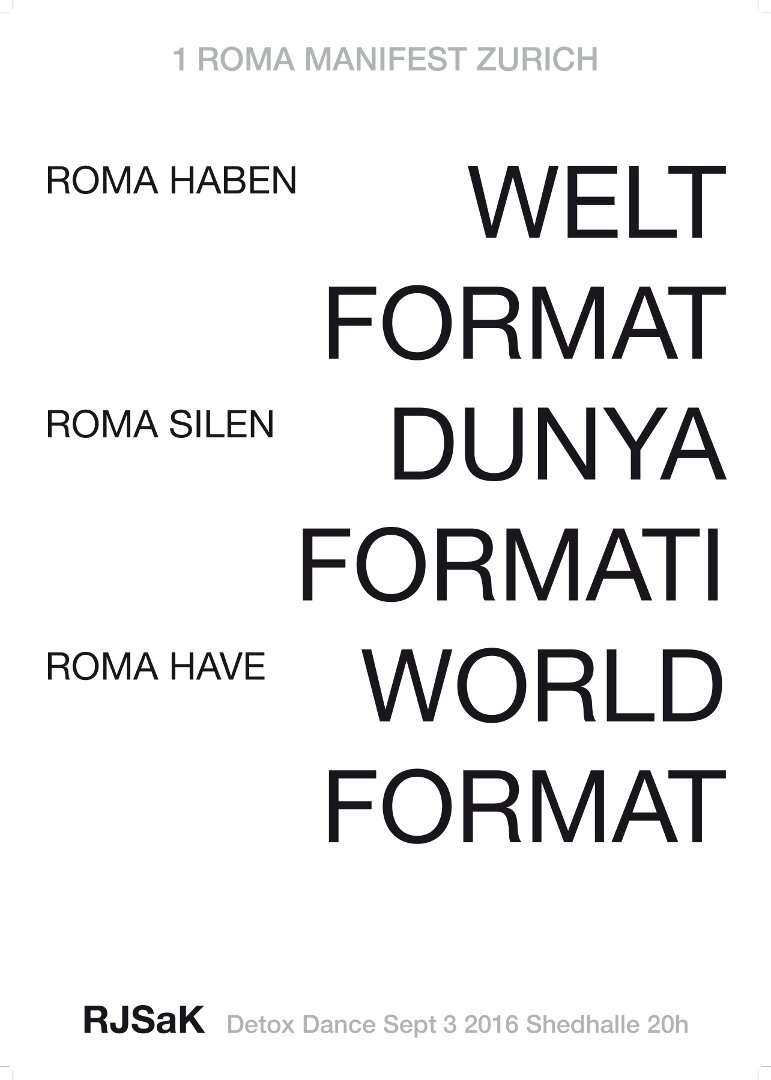

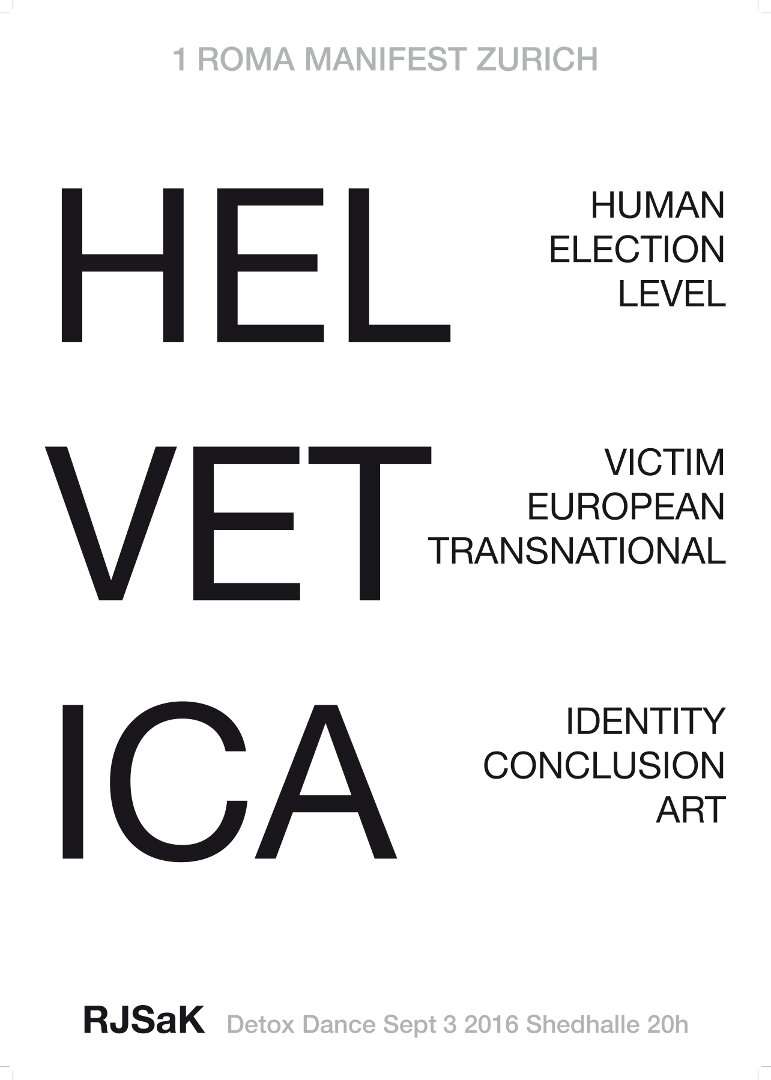

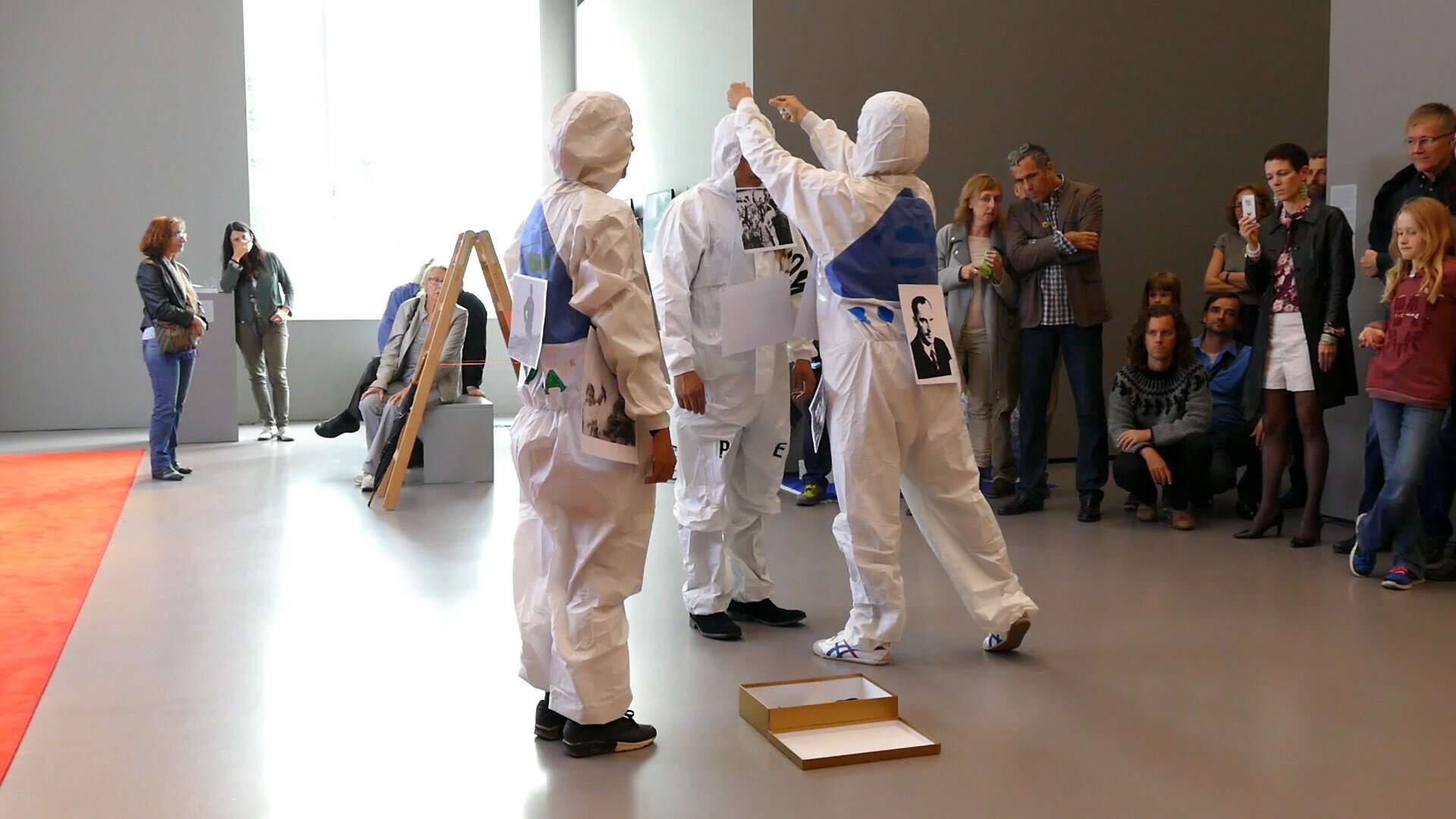

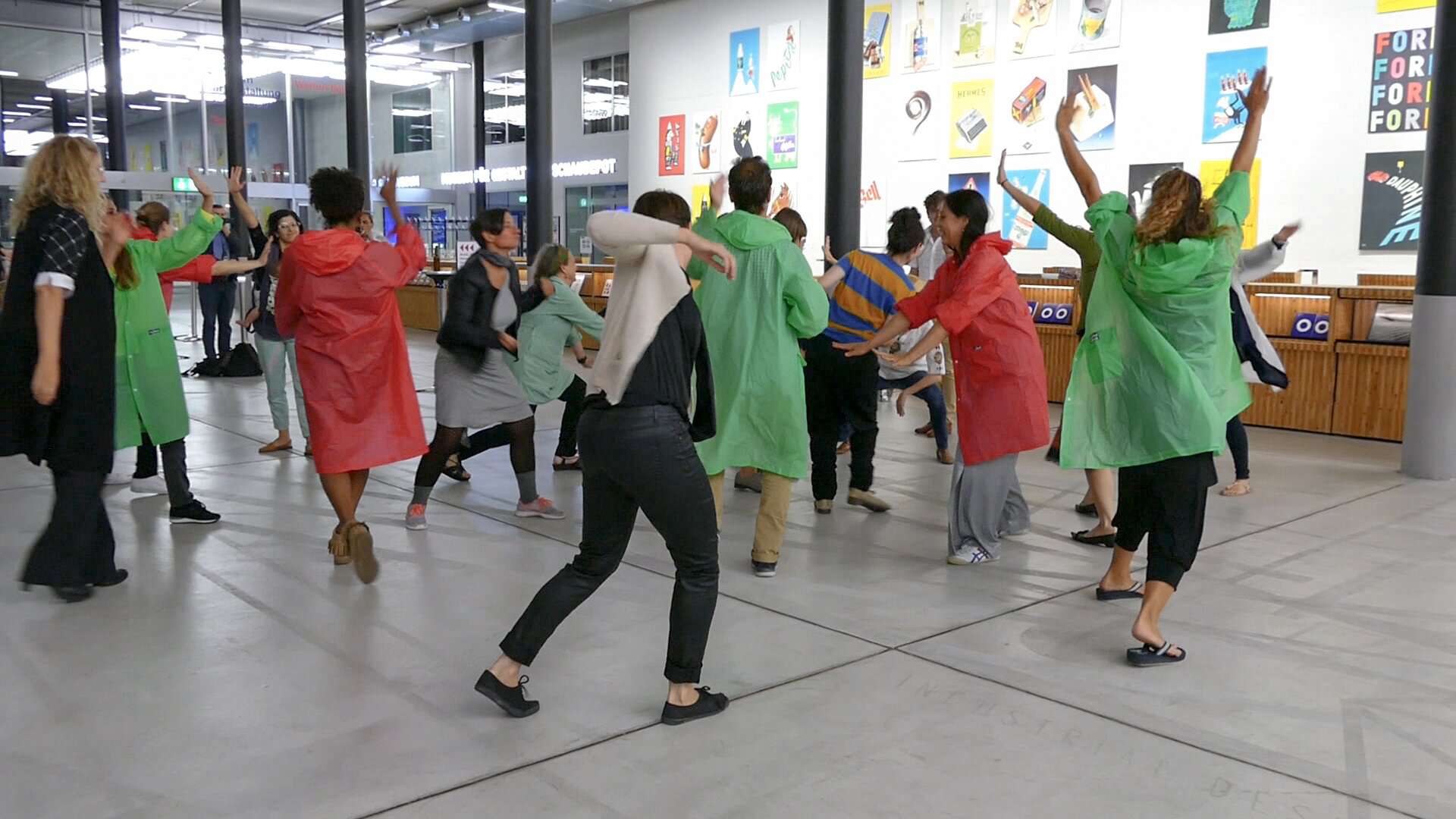

The Zurich-based collective RJSaK was established out of the similar necessity to bring invisible racial biases to light which even exist in one of the most democratic European societal contexts: Switzerland.

The collective brings together Roma, Sinti and Yenish artists and activists who are originally from Switzerland or from Balkan countries such as Macedonia and Serbia. Their public performances, exhibitions, panel discussions, publications and other activities are produced collectively or by individual members of the collective. (According to the RJSaK web site: ‘Roma Jam Session art Kollektiv (RJSaK) is the first art collective in Switzerland which is dedicated to making the Roma minority more visible in public sphere. Based in Zurich, the group works transdisciplinary with members from the arts, acting, and design, and collaborations with guests from different fields. Since its first intervention in 2013 at a local art space, RJSaK has performed in Zurich at the Shedhalle, Corner College, Maxim Theater and Toni Areal, as well as in other cities.’ The main members of the collective are Mo Diener, RR Marki and Milena Petrović, but many other more and less frequent participants and guests also join in with their activities. http://romajamsession.org/)

RJSaK’s art projects are clearly aimed at rewriting the ‘inherited’ protocols from the distant and recent past regarding not only Roma art and culture, but also cultural identity issues and the political and societal conditions of Roma in Switzerland and elsewhere.

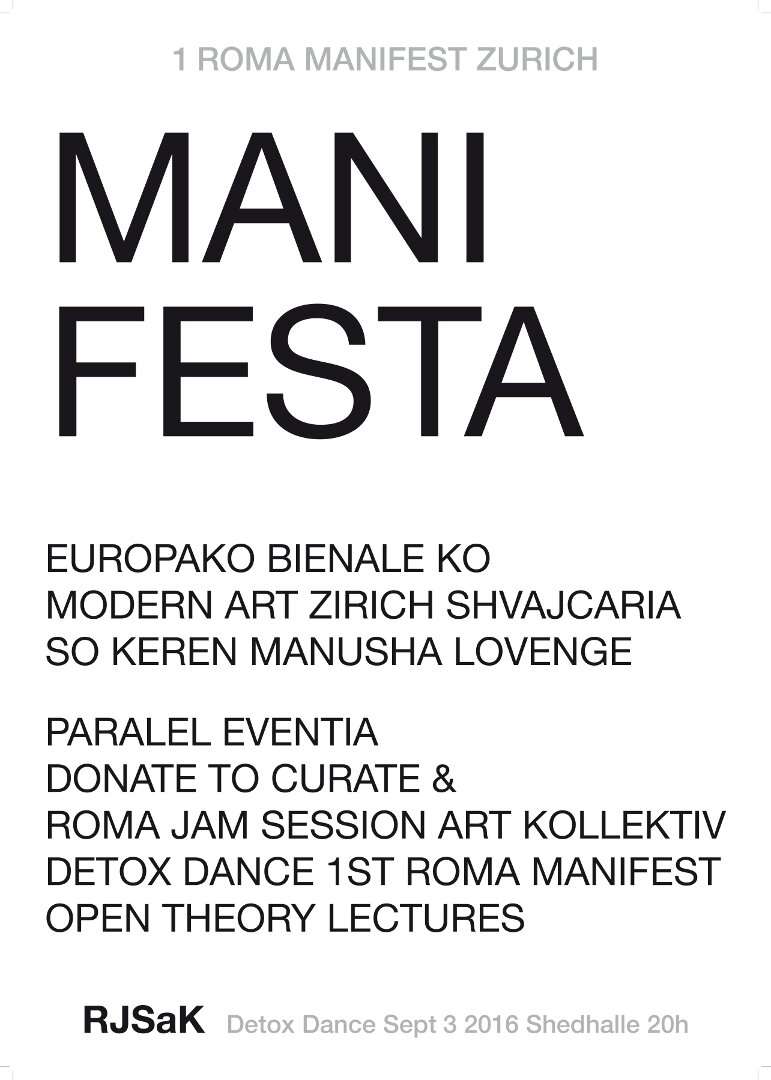

Some of their posters and slogans clearly point to the collective’s activist’s agenda. For example, until recently (September 2016) the status of Roma in Switzerland was not fully recognised and they were still referred to as ‘travellers’, so in reality Roma, Sinti and Yenish did not have full access to the rights which were accessible to other recognised minorities, as governed by existing laws.

(Yenish and Sinti communities in Europe have been officially recognised and protected ever since 1998, with the Council of Europe’s Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities. In 2001 the Swiss cabinet insisted that all Yenish and Sinti communities should be officially recognised by the Swiss authorities as a national minority, whether they pursued nomadic lifestyles or not. However, until 2016 the Swiss authorities often referred to Yenish and Sinti as ‘travellers’, although only 10 per cent of the 35,000-strong community actually move around.)

With a series of performances and other projects and posters (e.g. 1 Roma Dada Manifesto and Art History Hacking, both 2016), RJSaK also claimed a place for Roma and for their artworks in art history. Some of these self-historisation projects were part of the events marking the hundredth anniversary of Dada in Zurich, Dada Manifesto (1916).

These and other RJSaK activities (some of which were even included as parallel events to the European art biennial Manifesta 11) pointed to the long-term absence of artists of Roma origin from art history.

Despite the received knowledge about existing artworks by Roma artists in many different media, these works have not been carefully collected, systematised and published, and therefore mainstream art history fails to recognise how influential and relevant Roma artists really are.

The rewriting of art history protocols is therefore as relevant as the legal and political protocols, but of course one cannot be thought without the other because art history cannot be rewritten without systemic societal changes.

This project of the visual art’s section of RomArchive addresses the intertwining of different protocols and the reciprocal systemic relations between different theoretical disciplines, artistic practices and media, as well as the political, societal and cultural rules which regulate and construct them.