In the pre-1600 feudal era in Europe and the Middle East, we do find examples, much mocked by the 19th century Gypsy-lorists, of Roma attempting to negotiate with transnational and local feudal monarchs. The leadership that was capable of doing this, however, vanished in the 16th century outside the heartlands of the Ottoman Empire. Apart, perhaps from in Poland, they were unsuccessful in preventing the genocides and enslavements that accompanied the birth of the nation-state during the transition from feudalism to capitalism.

Beginnings and Growth of transnational Movements of Roma to achieve Civil Rights after the Holocaust

The result was that for more than 250 years there were no transnational Roma entities, which sought to negotiate with states or governments. There were various survival strategies – including military service – but none included challenging the state because early capitalism destroyed previous supra- national law, until it constructed its own.1 Roma politics up until 1945 was based on acceptance of marginalisation and submission to the nation-state, whose repression of the private violence (even as it institutionalised hierarchy and exploitation) that marked feudalism afforded basic protection of life to Roma and all their inhabitants from bodies other than the state.

This strategy began to fail from the middle of the 19th century, as industrial capitalism and the ideology of eugenics drove nation-states to ever more oppressive regulation of minorities. During this period, we find small local Roma organisations emerging, from New York to Sofia, seeking to negotiate with authority to protect Roma from the disruption of their lives by the urbanisation of industrial capitalism. But, although some claimed international reach, all of them were directed at particular states. Personal ties among Roma became broader in the 19th century because of migration, but the political strategy was still to evade rather than confront state power, which everywhere sought to regulate, assimilate or exterminate Roma and other metropolitan minorities. Nazi rule and the Holocaust to which it led, threatening the very existence of Roma people, made absolutely clear the failure of Roma strategies to evade state power.

The defeat of the Nazis, however, began the delegitimization of colonialism and racism, spurring on the interlocked struggles of anti-racism in the United States and anti-colonialism that provided different models of strategy to Roma. The establishment of the State of Israel was not at first seen by Europeans as traditional nationalism, but as a legitimate anti-colonial movement, which also inspired a number of Romani intellectuals in the 1950s, such as Matéo Maximoff, Ronald Lee and Vajda Voevod.

Who were the Romani intellectuals who began to dream of a different future for Roma after 1945? One important network was the Romani Nomenklatura in the Soviet Union, educated Roma working in the civil and military bureaucracies2. Their influence was mostly kept private, but they also had a public presence through the Teatr Romen 3. This group shared the kind of internationalism espoused by the (then) Soviet elite, often bolstered by travel during service in the armed forces and had a profound influence on Roma who visited Moscow or the Baltic republics from the countries who came together in COMECON after 1948, such as the Bulgarian Rom, Demeter Golemanov. The Romani Nomenklatura had to make its own accommodations with the communist authorities, but they were the root of the Central and East European intellectuals of today, along with the seminal association, Romano Phralipe, founded in Macedonia in 1947, whose members included Abdi Faik.

Further west, an artistic coterie of Roma writers and musicians began to form in Paris. Matéo Maximoff who was, in 1946, the first Rom writer to describe and denounce the Nazi genocide of Roma4; Maximoff had been in a Vichy concentration camp. He was part of the circle who founded Études Tsiganes, in 1953. At odds with his own Kalderash family (his mother was Manouche), he came under the protection of Stevo and Loulou, baré of the Demeter vitsa. They started the first Kalderash congregation of the Pentecostal, Light and Life Movement (La Vie et Lumière) in 1960, in Saint-Denis, a suburb of Paris. Although their congregations were separate, they came into contact with Manouche musicians, such as the violinist Charles Reinhardt. Part of this circle was Yul Brynner, of Russian and mixed heritage, a singer and circus performer who had come to Paris in the 1930s. Although he spent the war in the USA, broadcasting to the resistance in French, and had become a film actor there, he kept in touch with his Romani friends in Paris, supporting the International movement politically and financially to the end of his life. Another frequent visitor to engagements in Paris was the Yugoslav Rom, a balalaika virtuoso, Jarko Jovanovic, who first adapted the concentration camp version of the traditional ‘Gelem, Gelem’, for Yugoslav Radio in 1949. He later adapted it again, to become the Romani anthem at the First World Romani Congress, in 1971. The first Roma Ph.D. in linguistics, Jan Kochanowski, a refugee from Latvia, also settled in Paris.

Into this talented and eclectic group there erupted a would-be writer and painter, Ionel Rotaru, a Rom from Romania (or possibly Moldova), in 1958. In 1959, taking the title Vajda Voevod III, he staged a coronation of himself as ‘King’ of the Ursari Tsiganes. The ceremony itself was pure theatre, with engaging photographs by Paul Almasy distributed widely to the press5. These showed Rotaru and the previous Voevod, passing on the title by mingling the blood from their wrists in a Hollywood-style ceremony, which may be read as an ironic commentary on De Gaulle’s coup d’état founding the French Fifth Republic, a few months previously. The Declaration of the Rights of Man also featured prominently in the ceremony. His theatricality actually attracted the Paris Romani intellectuals who would subversively call themselves ‘the real Bohemians’. Unlike the Kwiek monarchy in Poland, Rotaru had both an immediate constituency of Roma immigrants to Paris from Romania and elsewhere, whom he helped, first with immigration matters and then, increasingly, with individual reparations claims against West Germany. The Roma intellectuals rallied to this cause. He was particularly helped by two half-brothers of mixed French and Rudari Roma heritage, Jacques and Louis Dauvergne, who took the political names, Vanko and Léulea Rouda. Vanko was a para-legal and allowed by his legal firm considerable time to take Roma cases pro bono. Together they founded two organisations, the Organisation Nationale Gitane (ONG), and the Communauté Mondiale Gitane (CMG). The latter is probably the first actual international Romani organisation. Although some previous organisations had international names, this was the first that had members in and from more than one country. These organisations published a journal, La Voix Mondiale Tzigane6 in 1961 (see The emergence of the Roma Civil Rights Movement in France) which lasted till 1968.

Vajda Voevod travelled tirelessly around Europe seeking recruits, even visiting London and the Irish Traveller struggle in Dublin, led by Joe Donohue and Grattan Puxon in 1964, recruiting them to the CMG7. He organised CMG pressure on the German government for reparations, collecting the names and stories of concentration camp survivors in several countries, and later pressing Puxon and Donald Kenrick to undertake their seminal research to back up the demand for holocaust reparations. On 26th February 1965, however, shortly before a visit from German Chancellor Erhard, the French government forcibly dissolved the CMG8, ostensibly because it had not complied with regulations about the membership of foreigners. Vajda Voevod, not holding a French passport, thereafter avoided France in the main and gave increasingly surreal press releases (see The emergence of the Roma Civil Rights Movement in France, p3) from different countries9.

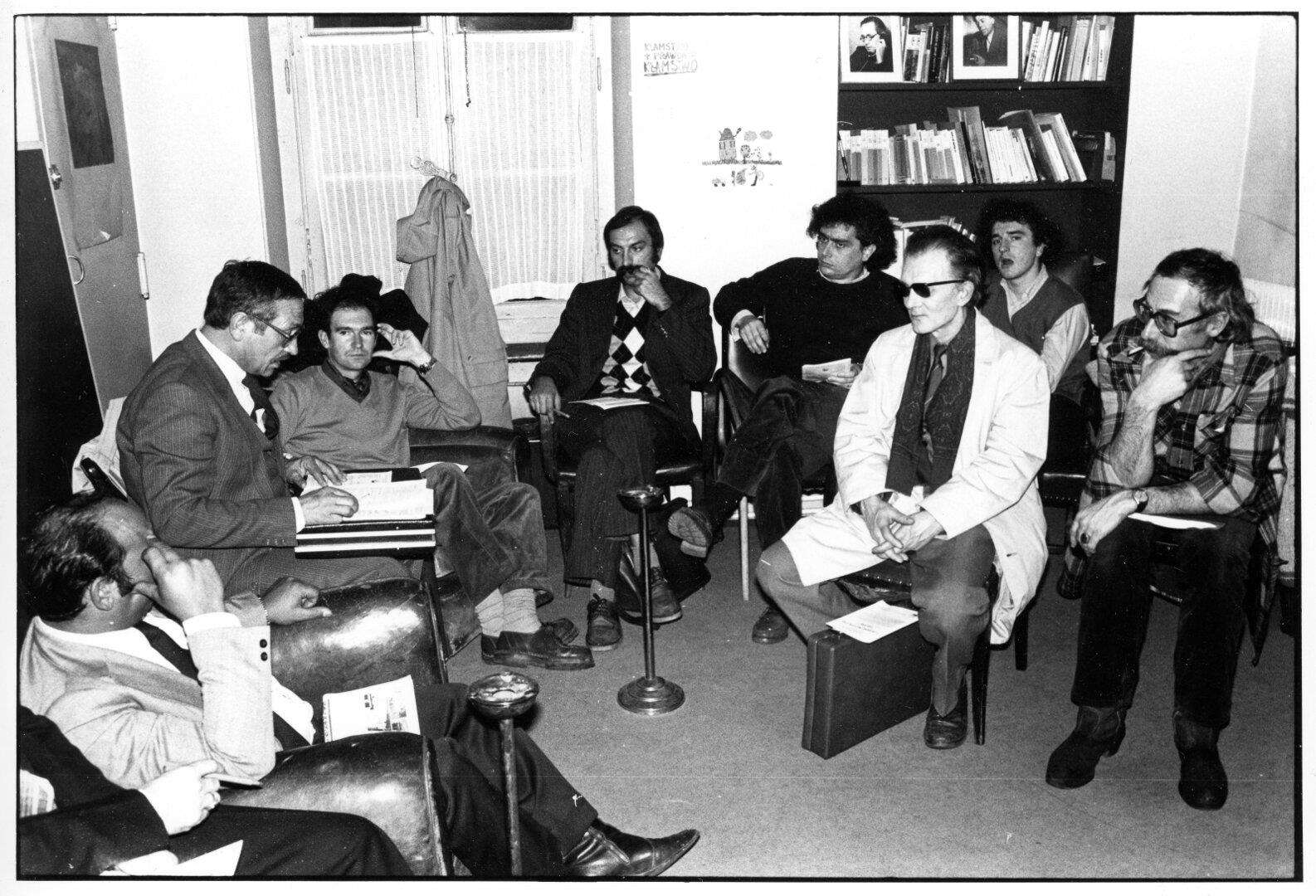

The major cause of dispute between Vajda Voevod and the other members of CMG was, however, a groundswell of accusations from Roma clients that he had charged too great a commission for pursuing individual reparations claims against the German government, on their behalf. During his absence from France, Vanko and Léulea Rouda took full control of La Voix Mondiale Tzigane and started a new organisation without Voevod, the Comité International Tzigane (which within a couple of years, changed its name to the Comité International Rom). This included all the celebrity, former supporters of the CMG and committee members from ten European countries, and Ronald Lee for North America and Miriam Novitch of the Holocaust Museum in Israel10, and began to reach out to Roma cultural organisations in Eastern Europe. Intermittent attempts at reconciliation with Vajda Voevod were made. In May 1971, after the 1st World Romani Congress, its Joint General Secretary, Grattan Puxon (supported by Jim Penfold, Tom Lee and Thomas Acton), attended a diwano in Paris to try to reach a compromise on the reparations issue. It was unsuccessful and Ionel Rotaru increasingly retreated into a position of absurdist situationism.Although the CIR was genuinely international in composition, the eyes of its leaders in Paris were still mainly focused on French Roma needs, whereas their foreign recruits were asking what an international organisation could do for their local situations and pressing for organisation of an international congress. Grattan Puxon persuaded the U.K. Gypsy Council, founded in 1966, that hosting a Congress would impress the British government. Vanko Rouda had his eyes set on a grand affair to be recognised by the Council of Europe and organised at the Palais de l’UNESCO and engaged in interminable negotiations to make this happen. Eventually, Grattan Puxon carried out a kind of coup d’etat. He organised a large cultural festival which was planned for Easter Monday on Hampstead Heath11. He invited the Paris committee members and the other organisations affiliated to the CIR and suggested, at the same time, they have a preparatory meeting immediately before, at Chelsfield School where GC member Brian Raywid had become the chef. Vanko Rouda, still dreaming of the Palais de l’UNESCO, accepted this and made the necessary travel arrangements. Then, a couple of weeks before the event, Grattan coolly announced that, as they had always hoped, the response and the numbers coming were so great that there was no alternative to declaring this event the First World Romani Congress. Dumbfounded, the CIR committee had no choice but to make the best of this fait accompli and enjoy the fruits of Grattan’s talent for publicity, particularly that generated by the associated, open-air musical festival on Hampstead Heath. Thus, it happened, that a small gathering of hitherto obscure activists became an event in world history.

This only happened, however, because those activists genuinely made history. Four of the delegates were women, itself a cultural innovation. The Congress forced the incredulous media to believe the impossible was happening and created a clear public record of their proceedings12. Everything said was in or was translated into Romani by Matéo Maximoff. They had the public ear of senior government figures in several countries, in both the capitalist and communist worlds. They managed to gain the support of academics and social work organisations, without letting them take a role in the Congress organisation. Thomas Acton was tasked to organise an academic conference at Oxford University, before the formal opening of the Congress, to divert the Gypsy-lorists and the Études Tsiganes contingent away from the discussions at Chelsfield (although Mateo Maximoff, Jan Kochanowski and Ian Hancock all spoke at this conference)13.

Roma were clearly seen as in charge, not as the adjuncts of non-Roma well-wishers.

They had the patronage of the Indian government through the participation of W. R. Rishi, an official at the London Indian High Commission. Indian backing of Roma cultural organisations in Eastern Europe enormously facilitated the possibilities for Roma to organise and have international contacts, as India took on the role of ‘original motherland’, within the Communist national minorities system. Delegates adopted the flag, anthem and agreed the International Romani Day (8th April), still observed today.

They also adopted a ten-point programme, proposed by Juan de Dios Ramirez Heredia (see Essay: A History of the Roma Associative Movement in Spain), (later to become an MP and MEP in Spain) and agreed a system of commissions, which for several years did manage to hold meetings14, although only when sponsors emerged.

Plans were made to have the next Congress at the Palais de l’UNESCO in Paris in 1973, and in Yugoslavia in 1975. Grattan Puxon resigned from the Gypsy Council and moved to Skopje to help build the international administration from there. The promised statutes, however, were not written, the Palais de l’UNESCO proved as elusive as ever and a national political crisis in Yugoslavia stopped plans there. Increasing impatience with the failure of Vanko and Loulea to get another Congress organised led to proposals for unilateral action from outside the inner circle. Anton Facuna from Bratislava, organiser of the Slovak Romani Union, sent the committee a draft, in Romani, of a set of statutes for a body called RIKSO (Romáñi Internacionálno-sociaálno-kultúrno organizaciá)15, with the slogan, ‘Andro amáro jekhetániben hi amáro zór!’ [sic]. Most of the members of the CIR supported the concept of these statutes becoming the basis of a second congress. The reference to this in discussions, by breakaway CIR members organising the second Congress, as ‘The International Romani Union’ in English, is probably the first use of this term. It was under this name that negotiations for funding and premises for the second congress were carried on, in 1977. Effectively, this makes 1977 the start of the IRU. Mateo Maximoff had started working with a Swiss radio journalist, who was outraged when Swiss border officials turned back the Schnuckenack Reinhardt band that he had commissioned, on the grounds that they were ‘Gypsies’. Together they persuaded the World Council of Churches to sponsor the Second World Romani Congress (8th to 12th April 1977), held at the John Knox Centre in Geneva.

The very full report in English and Romani, in the journal ROMA16, indicates that some 120 delegates and observers from twenty-six countries attended. A very substantial report on the legal position of Roma in Western Europe was adopted by the Congress and sent to the European Economic Community and the Council of Europe.17 There was and perhaps still is, some confusion about the statutes. The Facuna statutes were not adopted, as few delegates had seen copies18 and a commission was approved to revise the shortened translation that had been sent to the United Nations, which claimed to be the ‘International Committee’, which had organised both First and Second Congresses. The UN formally accepted this registration in 1979.

Unfortunately for this claim, the CIR continued to exist in Paris, led by Vanko and Léulea Rouda, who had not been elected to office in Geneva and disputed both the legitimacy of the IRU and the Second World Romani Congress. Indeed, when the CIR was reconciled to the IRU at the Third World Romani Congress in Gӧttingen, in 1981, it defiantly referred to that Congress as the Second World Romani Congress. However, no French delegate was elected to the IRU Praesidium in 1981.19

It had to be; no other kind of constitution would have enabled it to have affiliates in the Communist countries, under the Communist system, which was to endure for another twelve years. It was acceptable to the United Nations, because all the NGOs which presented from the Soviet bloc had to have such statutes at the time; it was normal. In the period 1971–1977, it was not possible to construct written statutes which could bring together the streetwise anarchists of western European Romani organisations and the cautious cultural manifestations allowed under state socialism. Informal agreements, negotiated by the Secretary Grattan Puxon, reflected the effective oral agreements built up in the 1970s; compromises over the leadership enabled the IRU to hold not only the 1979 Congress, but the 1981 Congress, hosted by Romani Rose in Germany, which was the last World Romani Congress attended by all the major factions. Rose became Vice-President, Sait Balič the President, and Rajko Durič the Secretary20.

After that, the mediating presence of Grattan Puxon was withdrawn when he moved to the United States, for personal reasons. It became politically impossible for Romani Rose to maintain such a system with the east Europeans and to build the fruitful long-term relationship of his organisation with the West German state. He has not attended a World Romani Congress since 1981. His great rival in Germany, Rudko Kawczynski, who had organised migrant Roma from Eastern Europe, came to the Fourth World Romani Congress, but was no more amenable to working within a system devised by former Communist bureaucrats than Romani Rose and the IRU has been without a substantial affiliate organisation in Germany since then.

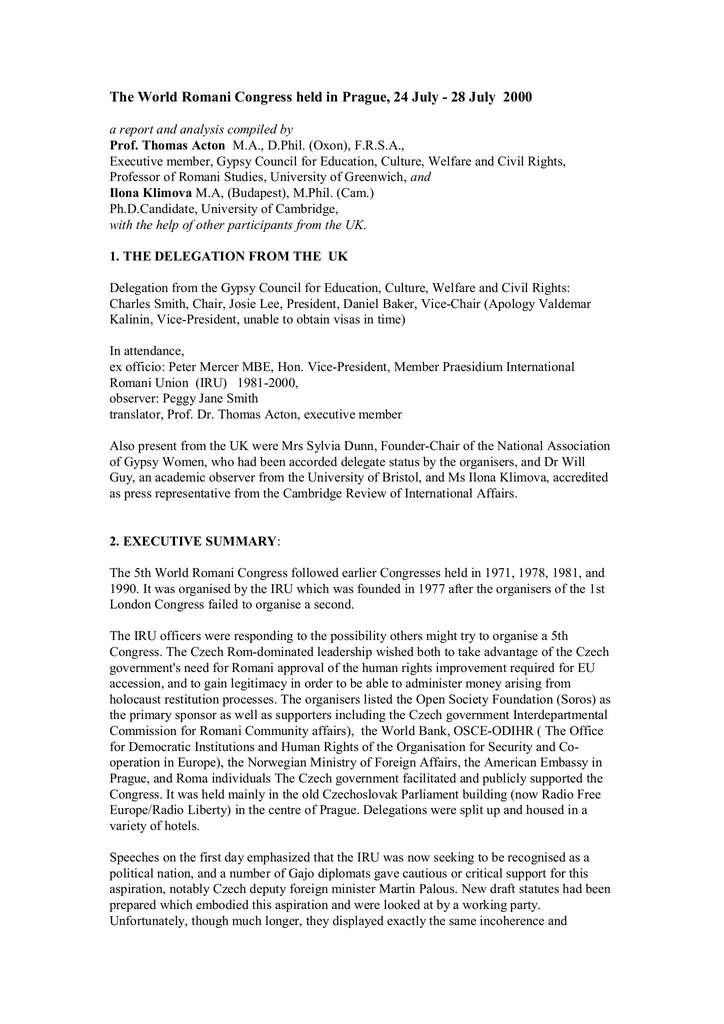

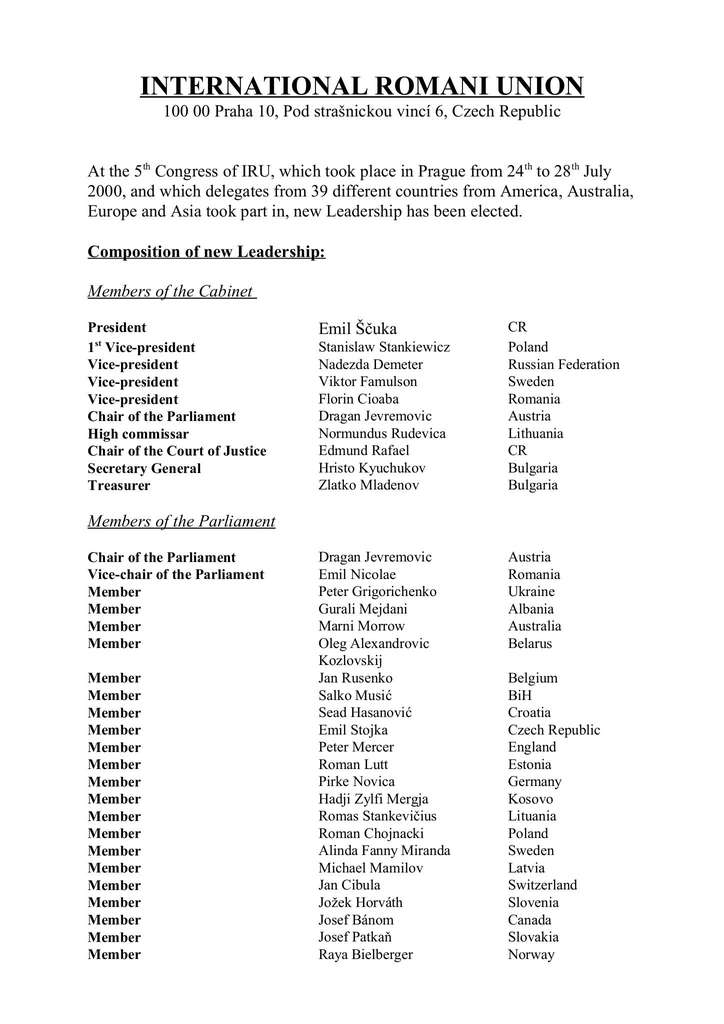

Nonetheless, in the 1980s, the IRU officers, mainly with the support of the academic activists Nicolae Gheorghe, Ian Hancock and Marcel Courthiade, continued to act as the major consultative party of international policy bodies21, securing registration with UNICEF as an NGO in 1986. But the Fourth World Romani Congress was held not till 8th – 12th April 1990, in Serock, Poland22. It was again only possible because of sponsorship by foundations, in this case, associated with the linguist Marcel Courhtiade. This Congress set important linguistic work in train and provided a huge opportunity to delegates from the former Communist countries to attend an international meeting for the first time. It failed, however, to gain the support of the most effective and well-resourced Roma activists, with both Rudko Kawczynski and Ágnes Daróczi, resisting the pressure put on them to take office. A large international congress held in 1994 to bolster the position of Spanish Romani organisations, by IRU member Juan de Dios Ramirez and with many IRU participants, did not identify itself as an IRU event.23In 1993, the IRU was raised to Category II Consultative Status at the UN. The leadership of Rajko Durič was however, erratic, arbitrarily replacing Ian Hancock as UN representative by a non-Romani politician from the Italian Radical, Paulo Petrosanti. After losing UN recognition, he relinquished the IRU presidency and the secretary, Dr Emil Ščuka, with Vice-President Victor Famulsen, set about organising a fifth Congress, which took place in Prague 24th – 28th July 200024.

Meanwhile in Germany, Romani Rose built perhaps the strongest of all national representative organisations, while Rudko Kawczynski had built the European alliance of grass-roots Gypsy, Roma and Traveller Organisations, which had most success in acting as a European negotiating partner; first in the Roma National Congress, then in the Standing Conference of Romani Organisations, as a rival to the IRU of the Fifth World Romani Congress. From 2004 until 2015, the European Roma and Traveller Forum, accepted co-operation from the IRU as just one member of that Federation, alongside evangelical and youth organisations. The presence in the ERTF leadership of women, such as Soraya Post (who went on to become the third Roma woman MEP), Ágnes Daróczi and Miranda Vuolasranta (see The Building Blocks of the Romani Women’s Movement in Europe) demonstrated the influence of the growing Romani women’s movement in a way that was lacking, at that point, in the IRU. ERTF’s internet presence became the most professional face of the International Roma Movement25.

Those Roma intellectuals who became important officials of international organisations, such as Nicolae Gheorghe and the Andrzej Mirga in the Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights, of the Organisation for Co-operation and Security (OSCE-ODIHR), helped to ensure ERTF’s status as a negotiating partner of the European Institutions for a while26. However, gradually the difficulties of maintaining a broad radical alliance and meeting European institutional demands grew. Rudko Kawczynski resigned and ERTF lost its European funding in 2015, continuing to exist as a pressure group.

The fifth Congress was, however, one of the largest and bolstered, like the first Congress, by an associated academic conference and the ‘Khamorro’ Cultural Festival, which became a continuing annual event. It secured for Emil Ščuka, the same level of recognition from the Czech government, that the third Congress had secured for Romani Rose from the German government. The fifth Congress managed the appearance of contested elections and one can, perhaps, see in the voting blocs that emerged, the roots of the three bodies claiming to be the IRU, since 2016. The Fifth World Romani Congress also echoed the re-invention of themselves, as nation-states, by the post-COMECON countries, through declaring the Roma, ‘A nation without a state’27. There was, however, no definition of what a nation is, thus allowing intellectuals who had already moved beyond nationalism as an ideology, such as Nicolae Gheorghe28, to continue the work within the IRU, to realise the dream that he had proposed in a pamphlet, written with Andrzej Mirga, to create a Roma elite29.

This new vision required new statutes, but these new statutes were no more workable than the 1978 statutes, a problem underlined by the lack of correspondence between the Romani and English texts to the statutes, which made it harder for those who sought improving amendments. The statutes themselves were a kind of caricature of a world government, replete with a separation of powers between Executive, (the Praesidium), Judiciary (the Kris) and Legislature (the Parlament) and huge numbers of grand-sounding titles for office-holders. However, the impetus of this revived IRU faltered, after Emil Ščuka suffered a disabling heart attack before the sixth Congress. SKOKRA, the Pan-American Association of Roma NGOs, founded in 2002 and including Jorge Bernal, Ronald Lee and Ian Hancock30 who were constantly in touch with Europe, did not link to any particular Europe-based organisations. The distinguished Italian Romani musician, Santino Spinelli, stepped into the breach to host the Sixth World Romani Congress at his studios in Lanciano, in 2004. Stanislaw Stankiewicz was elected President and retained the position at the Seventh World Romani Congress, held in Zagreb in 2008. The secretary in 2004 was Zoran Dimov and in 2008 was Bajram Haliti.

Lack of resources and the obvious dominance of ERTF in practical European politics, continued to make running the IRU a thankless task and in 2012, Bajram Haliti (with Jovan Damjanovič), held a founding electoral Congress of a new World Roma Organisation (WRO), in Belgrade31. Despite its links with some right-wing politicians in both Serbia and India, it was able to gain some support from longstanding IRU members, when it collaborated with the Indian government to hold an International Roma Conference and Cultural Festival in New Delhi, in February 201632. Meanwhile, the fracturing of the IRU continued. In 2013, Florin Cioabă, a Roma Pentecostal pastor who claimed to have inherited the title of ‘King’ from his father, Ion Cioabă, sponsored a congress in his home town of Sibiu, Romania, which elected him President. After his death, his brother Dorin Cioabă, simply declared himself the new President. Many of the long standing IRU stalwarts were outraged and gathered together as many of the office holders that they could from the Eighth World Romani Congress and held what they declared was the Ninth World Romani Congress of the IRU, in Riga in Latvia (2015). This elected Normands Rudevics President and considered, but ultimately rejected, proposals for democratisation via mass electronic voting, in a form proposed by Peter Antic and supported by the 8th April Movement, which had been founded by the veteran campaigner, Grattan Puxon, who had organised the first Congress in 1971.

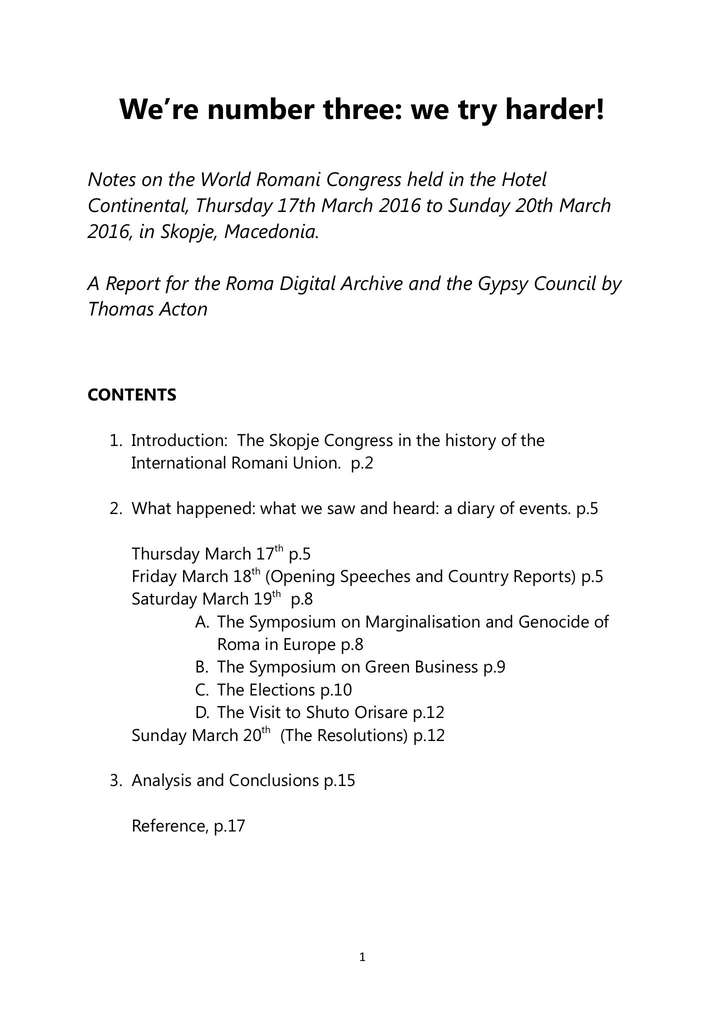

Other IRU members demanded Dorin Cioabă organise a ninth Congress, which was held later in 2015, in Sibiu. At this meeting he promised to answer all questions, given time. Zoran Dimov was elected Secretary to organise a meeting of the IRU Parlament, to decide on the future of the Cioabă presidency. When this meeting was held however, in Skopje, Cioabă did not attend and it was decided to hold a Tenth World Romani Congress in Skopje 17th – 20th March 2016.

This Congress elected Zoran Dimov as President and gathered support, because it did decide that the IRU should move towards a mass electronic voting system. .

Rudevics, in Riga and Cioabă in Sibiu, however continue to run organisations, each of which declares itself to be the legitimate IRU33. With the WRO, there are now four organisations seeking to represent Roma throughout the world, while SKOKRA (see Development of Roma Civil Rights Movements in Argentina and Latin America) and ERTF, continue to claim a pan-American and a pan-European mandate. The WRO also claimed its meeting in Budapest, in June 2017, was the ‘Ninth World Romani Congress’. Frustrated by a disunity, which paradoxically has done little to promote diversity, many Roma intellectuals and Eurocrats have decided instead to focus their activities on the new European Romani Institute for Arts and Culture, founded in 2017.

This disunity may obscure the considerable progress that has been made. Lacking authority within the community, like all Roma NGOs, the international organisations have to tread the delicate line between accommodating and challenging non-Roma authorities. Before 1971, the idea of international Romani organisation seemed an impossible dream. Now it is unthinkable that transnational bodies should not consult with Roma; the complaint of international authorities, echoes the traditional charges against non-Roma politicians, that they are disunited and inefficient. Perhaps the best response to this complaint was made by the oldest delegate from Romania, at the fourth Congress. The outgoing President, Sait Balič, frustrated by the lengthy disputes within the thirty to forty-strong Romanian delegation, stopped the session for a half-hour coffee-break and told the Romanian Roma to go to a room and decide how they would cast the Romanian vote without perpetual argument. Loud voices were heard from within the room and eventually they filed back into the main hall. Their oldest delegate, a Pentecostal pastor in his eighties, spoke for all of them for once, ‘For many years, under communism, we were told we all had to say the same thing. Then we had our revolution. Now no-one will ever tell us again that we have to speak with one voice!’ The complexity and diversity of international Romani politics are probably here to stay.

Rights held by: Thomas Acton | Licensed by: Thomas Acton| Licensed under: CC-BY-NC 3.0 Germany | Provided by: RomArchive